Former SLAC Intern is Youngest to Lead LCLS Experiment

Stephanie Mack, 20, read and reread the email in disbelief.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

Stephanie Mack, 20, read and reread the email in disbelief. After spending time during the past two summers in a science internship program at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, she was heading back.

This time she would be at the helm of the world's most powerful X-ray laser, leading an international collaboration as the principal investigator in an experiment exploring how to precisely control the motion of electrons in specially prepared samples of a mineral called manganite.

Steep Competition for LCLS Proposals

"I didn't really believe it at first," Mack said, when she first learned in October that a proposal review panel had selected her proposed experiment at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source. "I definitely read the email several times. I ran downstairs and told my family I was going to get to go back to SLAC soon."

One of the things that gave her pause: "It was addressed to 'Dr. Mack,' " she said, which was an obvious oversight given she is an undergraduate student, and the youngest principal investigator yet to lead an LCLS experiment.

"It's kind of weird being so young – I can't rent a car but I can run an X-ray laser," she reflected in March, as she prepared for the experiment at SLAC.

Winning approval to conduct experiments at LCLS is extremely difficult because the X-ray laser is in such high demand – only one in four proposals is accepted, and many of the world's leading research collaborations try.

Mack credits the U.S. Department of Energy's Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship program she participated in at SLAC, the mentorship of LCLS instrument scientist Joshua Turner and guidance from members of the Soft X-ray Materials Science (SXR) instrument team and other SLAC staff in preparing her for the LCLS experiment.

"Stephanie did a great job in her summer internship with us at SLAC. I overloaded her with multiple projects and she showed great promise as a young scientist in all the important areas to be successful: handling a variety of different types of work, working hard and asking lots of questions," Turner said.

A Nebraska native who moved to Canada at the age of 9, Mack is graduating from University of Ottawa in June, a college that has been building up its photon science research program. She has long been drawn to science and mathematics, and she said physics has proven a good blend of her interests.

Physics 'Rebel' Credits Support of SLAC Staff

Mack had earlier considered a career as a surgeon, but, she said, "I knew I didn't want to do med school," a career path that is all too familiar in her family: Her dad is a doctor, and her mom and older sister are nurses.

"I was the rebel going into physics," she said. "When you do science you never know what you're getting into and that's really part of the fun.

"I think of the technology around today that would never have happened if it wasn't for this basic science," she said. "Even the laser itself – with the X-ray laser you're able to do so much that wasn't possible before."

It was during her past summer internship at SLAC that Mack observed an LCLS experiment for the first time, and during that same summer she worked with Turner as she helped draw up the proposal for an LCLS experiment.

"Everyone here really wants to help," she said of the training and support she has received from LCLS staff. "It is a great atmosphere."

Controlling the Orbits of Electrons

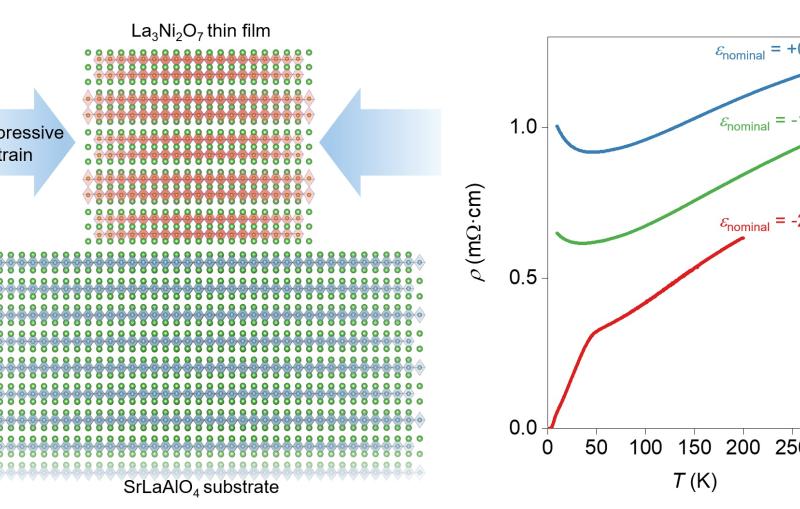

The LCLS experiment required a laser tuned to a terahertz wavelength, which lies between microwave and infrared wavelengths, that was designed to excite and control electrons in specific orbital positions that are close in energy. The X-ray laser pulses were used to explore the behavior of these orbitals as they reacted to the terahertz laser light.

"Other groups have looked at orbital ordering in similar types of materials," Mack said. "We are first to look at the orbital’s response to THz electric fields on these very short, dynamic timescales, an area in materials research that has been largely unexplored."

Controlling the orbital motion of electrons with laser light could lead to ultrafast computing. Another field of laser research that has been the subject of LCLS experiments is "spintronics," which also uses laser light to control the flipping of electrons' orientation. Orbital electronics could, in theory, work many hundreds of times faster than spintronics.

She credited her collaborators – from SLAC and Stanford, the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Argonne National Laboratory, the University of Tokyo and RIKEN in Japan, and Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland – in bringing the many parts of the experiment together.

Collaboration is Key

"I think a lot of people underestimate how much interpersonal collaboration there is in physics," Mack said – an observation which bucks the stereotype of "loner" scientists.

Just over a dozen scientists participated in the experiment, which is actually a small crew compared to some LCLS experiments that bring together more than 30 scientists.

There was an intense buildup of communication as the experiment approached. "There were a lot of emails," Mack said, including daily feedback on "what's happening, what's going to happen."

The experiment was conducted during four night shifts at LCLS, which run from 9 p.m. to 9 a.m.

"Overall I think the experiment went well," she said, recalling the large number of tasks that had to be delegated to ensure all bases were covered during the nights. "We think we have some promising results, but you'll have to stay tuned."