Surprising Competition Found in High-Temperature Superconductors

A team led by SLAC and Stanford scientists has made an important discovery toward understanding how a large group of complex copper oxide materials lose their electrical resistance at remarkably high temperatures.

By Mike Ross

A team led by SLAC and Stanford scientists has made an important discovery toward understanding how a large group of complex copper oxide materials lose their electrical resistance at remarkably high temperatures.

The materials in question are high-temperature superconductors, which conduct electricity perfectly with no resistance when cooled below minus 100 degrees Celsius.

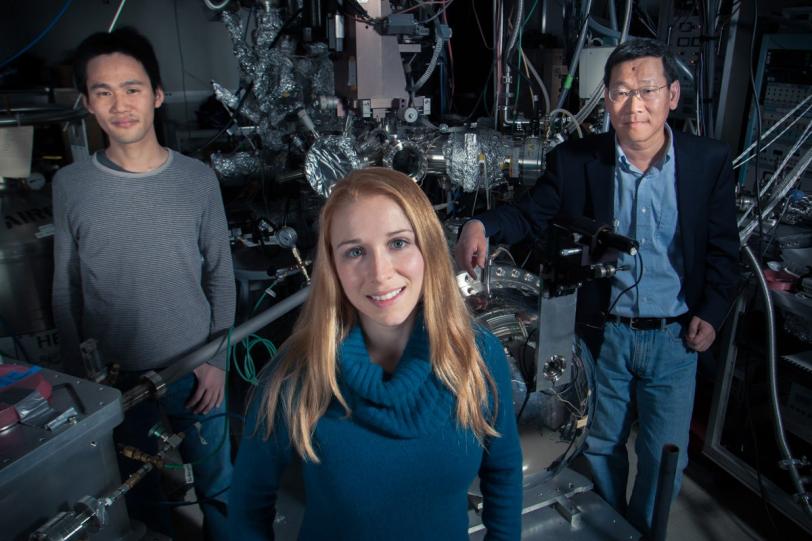

In a report published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers led by SLAC Chief Scientist and Stanford Professor Zhi-Xun Shen describe the surprisingly complex and dynamic way that the electrons organize themselves within one group of copper oxide superconductors, known as cuprates. They created a complete phase diagram of the material – a roadmap of its properties – over a range of compositions and temperatures that are ideal for superconductivity.

Earlier experiments had shown that non-superconducting behavior – the so-called pseudogap phase – can occur within cuprate superconductors. In this study, the researchers were surprised to discover that this pseudogap phase actually coexists and competes with the superconducting phase over a wide range of temperatures and compositions.

“The pseudogap is one of the biggest mysteries in high-temperature superconductivity,” said Inna Vishik, a Stanford graduate student in Shen’s group who is first author on the PNAS paper. “We had thought that the pseudogap did not notice the onset of superconductivity. But that is not the case. As temperature decreases, superconductivity actually suppresses the pseudogap phase.”

Learning the details of this competition between the pseudogap and superconducting phases should aid researchers in their ultimate goal of creating new superconducting materials that operate above room temperature – an advancement that would revolutionize myriad modern technologies, from tiny computer chips to miles-long power-transmission lines.

“Twenty-five years after the discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in cuprates, this experiment has brought out important new aspects of the phase diagram that had been hidden,” Shen said. “Since the phase diagram is fundamental to understanding matter, describing the nature of the phases and the intricate relationship among them, this work is an important step forward.”

The complex electronic structure of cuprate superconductors has made it very difficult for scientists to determine exactly how these materials lose their electrical resistance, let alone how to modify them to make this transition occur above room temperature.

In recent years, Shen’s research group has helped develop a technique called angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES), which enables scientists to see electron interactions in much more detail than before.

To explore the properties of the pseudogap and superconducting states, Vishik systematically varied the composition of a superconducting cuprate containing bismuth, strontium and calcium and performed hundreds of ARPES measurements on those samples in Shen’s Stanford lab and at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource.

Future research is aimed at nailing down the exact electron behavior of the pseudogap phase and the details of its competition with the superconducting phase, as well as determining exactly how electrons pair up to create superconductivity in the copper oxides.

The research involved scientists from the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences, which is jointly operated by SLAC and Stanford; Boston College, Cornell University and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the United States; Shandong University in China; Suranaree University of Technology in Thailand; and the Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan Atomic Energy Agency, University of Tokyo and National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Japan.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.