Dialing gravitational lensing research up to 11

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science, will add an unprecedented amount of cosmological data to the study of the structure and expansion of the Universe.

By Kimberly Hickok

SLAC completes construction of the largest digital camera ever built for astronomy

Once set in place atop a telescope in Chile, the 3,200-megapixel LSST Camera will help researchers better understand dark matter, dark energy and other mysteries of our universe.

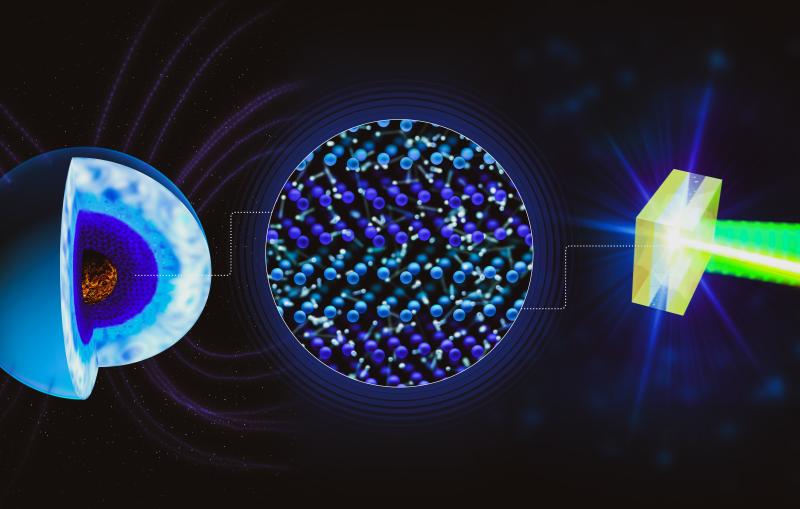

Before light from distant stars can reach telescopes on Earth, it must travel through space. Its path is not always a straight one. Massive objects like the Sun warp space around them. When light is bent on its way through a warped area of space, the effect is called gravitational lensing.

Astrophysicists map dark matter by statistically analyzing the subtle distortions in the shapes of distant background galaxies. These distortions are caused by the gravitational lensing effect of massive objects like galaxy clusters or the cosmic web in the foreground.

“We can use the gravitational lensing effect to measure the invisible dark matter that we otherwise wouldn't be able to see by looking at the images of distant galaxies and seeing how they've been distorted by the matter between us and that galaxy,” says Theo Schutt, graduate student at Stanford University’s Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology and the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

The more images the scientists can take of the same area of the sky, the deeper the combined image becomes. Deeper images mean a more accurate understanding of the invisible mass that warps the light that arrives from afar. But the number of images astrophysicists can use is limited by the power of the telescope and the speed at which the scientists can analyze them.

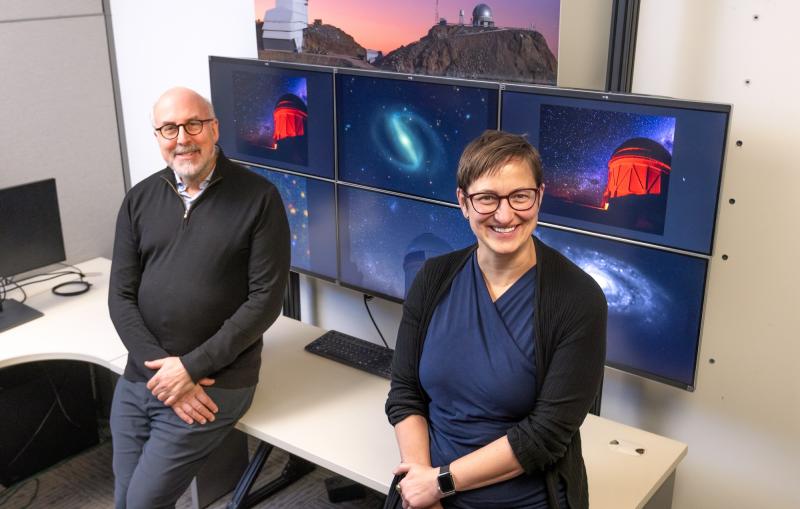

Deputy Director of Operations for the Rubin Observatory and Senior Scientist at SLAC National Accelerator LaboratoryWe’ll be able to detect and measure orbits of enormous numbers of stars, galaxies, and Solar System objects that are hard or impossible to see with current telescopes.

Later this year, scientists will push one of those limitations with the start-up of the NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory and its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). Rubin Observatory is jointly funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. Rubin Observatory is a joint Program of NSF NOIRLab and DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, who will cooperatively operate Rubin. Rubin’s LSST Camera will photograph the night sky with unprecedented detail, depth, and scope. The survey will collect more than 20 terabytes of data each night over a span of 10 years, resulting in a volume of data several magnitudes greater than anything cosmologists or astrophysicists have dealt with before.

“We’ll be able to detect and measure orbits of enormous numbers of stars, galaxies, and Solar System objects that are hard or impossible to see with current telescopes,” says Phil Marshall, deputy director of operations for the Rubin Observatory and senior scientist at SLAC.

The issue will become: How will they overcome the other limitation, the speed at which they can analyze those images?

“The numbers are anxiety-inducing but also very exciting,” Schutt says.

For each patch of sky, Rubin will ultimately capture several hundred images. Scientists who study gravitational lensing must develop new, more efficient methods to identify and analyze gravitational lenses.

What is gravitational lensing?

In cosmology, there are two main types of gravitational lensing: weak and strong.

Weak gravitational lensing describes a relatively minor effect. “The galaxy shapes we see are mildly changed from what we would have seen if there were no mass interfering,” says Rachel Mandelbaum, astrophysics and cosmology professor at Carnegie Mellon University.

When weak lensing occurs, it happens in a coherent way, Mandelbaum explains. The shape or image of all objects in an area are changed in the same way. “We look for those coherent patterns and that’s how we know that weak lensing has happened.”

While the light from every galaxy in the Universe experiences some weak lensing on its way to Earth, the light from a rare few galaxies experience a different type of lensing.

Strong lensing occurs when a distant galaxy lies directly behind another massive object. This alignment distorts the light from the background galaxy so that it wraps around the massive foreground object in multiple spots. This effect causes an observer on Earth to see multiple images of the same distant object.

Imagine looking at a particular massive (usually yellow and elliptical) galaxy that has a faint blue galaxy exactly behind it, Marshall explains. “It’s not that you don’t see that background galaxy because it's obscured; you see it because the light from that background galaxy has started out in one direction, then it’s been bent around the massive galaxy in the foreground and has ended up in your telescope.”

One way scientists can learn about the distance to massive galaxies in the Universe is by watching how their mass lenses light over time. If a galaxy has a supermassive black hole in it, for example, the light from matter orbiting the black hole will flicker. “The time delay between flickers can tell you something about the distances between us, the gravitational lens, and the active galaxy in the background if you know what the mass of the gravitational lens galaxy is,” Marshall says.

What will Rubin deliver?

At roughly the size of a car and twice the weight, the Rubin Observatory’s LSST Camera is the largest digital camera ever built. The 3,200-megapixel camera will be able to capture images of billions of galaxies.

Rubin Observatory’s LSST will help scientists study the gravitational lensing they’ve already seen. It will also help them greatly increase their catalogue of examples. Scientists know of about 1,000 strong gravitational lenses right now, “but with Rubin we should be able to get to a few tens of thousands,” Marshall says.

In the past 5 to 10 years, cosmologists have observed a small number of strong gravitational lenses from supernovae, the explosive deaths of stars. But “Rubin will be a game changer,” says Simon Birrer, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Stony Brook University. “We expect to increase that by at least 100 times and to see about 50 lensed supernovae per year.”

When it comes to weak lensing, the jump will also be substantial — from a few hundred million examples to billions of them. “It’s not just that we have more area, but we’ll be able to go a lot deeper so we can see much fainter galaxies,” Schutt says.

Researchers also anticipate gaining new insights by combining Rubin data with information from previous and concurrent experiments. These include the DOE-funded Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) survey, conducted using the NSF Nicholas U. Mayall 4-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, a Program of NSF NOIRLab; the Dark Energy Survey, conducted using the DOE-fabricated Dark Energy Camera (DECam), mounted on the NSF Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, a Program of NSF NOIRLab; and the European Space Agency’s Euclid Space Telescope.

“Of course, we need to analyze each of these data sets independently, and we need to understand them well,” Mandelbaum says. “But what I think is particularly powerful, for example, is having spectroscopy and imaging over the same area like the overlap region between LSST and DESI, which will be extremely interesting.”

This deeper probe of the Universe will also allow researchers to better track how galaxies and other large structures formed in our Universe, Schutt says, as looking farther away in space means looking at light that originated farther back in time.

Sharpening our cosmic focus

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory is gearing up to illuminate the universe’s darkest secrets with groundbreaking new technology.

How will scientists prepare?

In the short term, receiving a tidal wave of data from Rubin will be a huge challenge, Mandelbaum says. “The first thing that happens when you try to analyze a new dataset is that you find a problem, and then you have to fix the problem.”

“But in the long term, we'll have a lot more cosmological information,” she says. “So if we can do the analysis right, we'll be able to significantly advance our understanding of the cosmological model and dark energy.”

One of the ways researchers are preparing is by practicing — testing simulations and analysis pipelines on the scale of Rubin data to make sure that their outputs are logical.“Based on what we know from previous surveys, we can at least make sure that our simulated results make sense in some way,” Mandelbaum says.

Two scientific collaborations associated with LSST have been issuing public open data challenges, asking participants to find strong gravitational lensing in simulated data, Birrer says. “We want to involve as many people as we can to learn how to deal with the data infrastructure that we are using.”

Through the Rubin Science Platform, collaborators from around the world can begin to familiarize themselves with the kind of data Rubin is expected to produce. “It will be a bit of a Wild West when we start receiving data,” Birrer says. “We will have to learn things on the fly, but at least we will try to be as ready as possible.”

Community will be key to making the most of the Rubin data deluge, the researchers say. “Community software development is more important than ever,” Mandelbaum says.

If each survey collaboration builds its own cosmological simulations, image simulations, and analysis software, there is likely to be a lot of duplicated effort, she says. That also makes comparing results difficult.

“There is significant value in community software efforts that people in multiple surveys can contribute to,” she says. “We can do better science together.”

The strong lensing community will need to grow their collaborative efforts, too, Birrer says. “With Rubin, we can’t do the research alone,” he says. Organizing larger research teams will be a shift for the strong lensing community, he says, “but it’s exciting because together we can do something really substantial.”

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

More information

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, is a groundbreaking new astronomy and astrophysics observatory under construction on Cerro Pachón in Chile, with first light expected in 2025. It is named after astronomer Vera Rubin, who provided the first convincing evidence for the existence of dark matter. Using the largest camera ever built, Rubin will repeatedly scan the sky for 10 years and create an ultra-wide, ultra-high-definition, time-lapse record of our Universe.

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory is a joint initiative of the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science (DOE/SC). Its primary mission is to carry out the Legacy Survey of Space and Time, providing an unprecedented data set for scientific research supported by both agencies. Rubin is operated jointly by NSF NOIRLaband SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. NSF NOIRLab is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) and SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the DOE. France provides key support to the construction and operations of Rubin Observatory through contributions from CNRS/IN2P3. Rubin Observatory is privileged to conduct research in Chile and gratefully acknowledges additional contributions from more than 40 international organizations and teams.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency created by Congress in 1950 to promote the progress of science. NSF supports basic research and people to create knowledge that transforms the future.

The DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

NSF NOIRLab, the U.S. National Science Foundation center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the International Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), NSF Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory (in cooperation with DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona.

The scientific community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on I’oligam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence of I’oligam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) to the Tohono O’odham Nation, and Maunakea to the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) community.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators. SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.