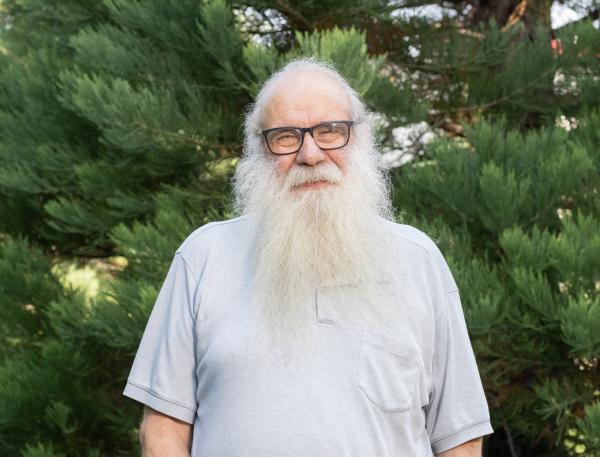

Jim Sebek wins 2023 Lytle Award for decades of synchrotron problem solving and dedication

Sebek’s extraordinary career at SSRL includes helping build the facility’s original electron injector back in the 1980s and working on almost all of its electrical systems since.

By David Krause

Jim Sebek, an electrical engineer and physicist at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, will receive this year’s Farrel W. Lytle Award for countless contributions towards building, maintaining and operating the synchrotron for nearly four decades.

The annual award recognizes staff members and SSRL users, and no one has done more to keep SSRL and its accelerator running over the years, SSRL senior scientist James Safranek said.

“An attempt to describe the many times that Jim has led the effort to get SSRL accelerators back online would not take a book. It would require volumes,” Safranek said. “He takes an interest in solving any problem, whether it is with power supplies, beam diagnostics, computer controls or the HVAC system. If there is a problem, Jim is addressing it.”

Over his 39 year career, Sebek has worked on almost all of the electrical systems at the Stanford Positron Electron Accelerating Ring (SPEAR), the particle accelerator at the heart of the synchrotron facility. His job description may be summarized as “fix whatever needs fixing,” Safranek said.

Sebek credits his skills and knowledge to his mentors, who have been willing to spend time to teach their expertise, even during the busiest times at SSRL. Sebek actually started working at SLAC before he finished his undergraduate degree. He learned technical subjects related to the operation of an accelerator on his own, completing morning and evening classes at San Jose State University. He’d take classes that could help him solve immediate problems at SSRL and SPEAR – if a beam control system was acting oddly, for example, he’d take a course about feedback, he said.

“I enjoy reading technical books and applying new ideas to SPEAR. In the past, I took math and science classes before or after work,” Sebek said. “This is what I like to do with my free time.”

He went on to complete a PhD in accelerator physics at Stanford, after mentors at SSRL encouraged him to pursue his degree and publish papers based on his experience.

Building a particle injector from scratch

Sebek did not ease his way into working at SSRL: His initial job was to help build the dedicated electron injector for SPEAR that decoupled it from the SLAC linac. Until the 1980s, SPEAR was connected to SLAC’s linear accelerator and was used to study high-energy physics. In 1988, SPEAR transitioned into a stand-alone synchrotron radiation source that generates X-rays for SSRL. Sebek was hired as an electronics instrumentation engineer on the new injector project, which took about two years to finish.

The injector project offered opportunities to learn about all aspects of an accelerator. During the project, Sebek learned another new subject: how to modify and repair large magnet power supply systems to help the synchrotron run reliably.

“My career has been a progression along these lines: I find something that needs work, so I start working on it,” he said. “I migrate from one system to another and learn about them as I go.”

He’s lost count of the total number of titles and roles he’s held. This broad experience is one of his favorite parts of his career.

“In some positions at SLAC, you become highly specialized in one particular thing, but at SPEAR, things are different,” he said. “Our primary goal is to make sure the accelerator runs reliably, which means we have to know a lot about all of its parts. This helps us fix things outside of our immediate assignments.”

Jim Sebek

(Jacqueline Orrell/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

His journey to SLAC started in 1979, when he left his hometown of Chicago for the San Francisco Bay Area. He did not know then that he would spend the better part of his life working as an engineer and physicist at SSRL. He liked to tinker with mechanical things and study math growing up, but he did not have a clear sense of what path he would travel on when he arrived in California.

“SSRL and SLAC as a whole was a mystery to me before I started working here,” he said. “I’d heard about the lab and read a little about it, but until I started working here, I really did not know what went on inside.”

The lab ended up being a “good working environment with good people who are a pleasure to work with,” he said. “I enjoyed it and stayed on.”

His favorite project was researching, understanding, and ultimately curing beam instabilities that had caused operational issues in SPEAR2, the next generation of SPEAR. He also enjoyed contributing to the design, construction, commissioning, and operation of SPEAR3.

He remains fully engaged in keeping SSRL running. “But time goes on and nobody stays at SSRL forever,” Safranek said. “SSRL does have a succession issue – Jim is simply irreplaceable.”

The Lytle award will be presented at the 2023 SSRL/LCLS Annual Users’ Meeting that will take place at SLAC from September 24 to 29. SSRL is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.