The Rubin Observatory's giant data acquisition system

The Rubin Observatory's LSST Camera will take enormously detailed images of the night sky from atop a mountain in Chile. Down below the mountain, high-speed computers will send the data out into the world. What happens in between?

When the Vera C. Rubin Observatory starts taking pictures of the night sky in a few years, its centerpiece 3,200 megapixel Legacy Survey of Space and Time camera will produce an enormous trove of data valuable to everyone from cosmologists to the people who track asteroids that might collide with Earth.

You may already have read about how the Rubin Observatory's Simonyi Survey Telescope will gather light from the universe and shine it on the Department of Energy's LSST Camera, how researchers will manage the data that comes from the camera, and the myriad things they'll try to learn about the universe around us.

What you probably haven't read about is how researchers will get that mountain of incredibly detailed images off the back of the world's largest digital camera, down fiber optic cables and into the computers that will send them off Cerro Pachón in Chile and out into the world.

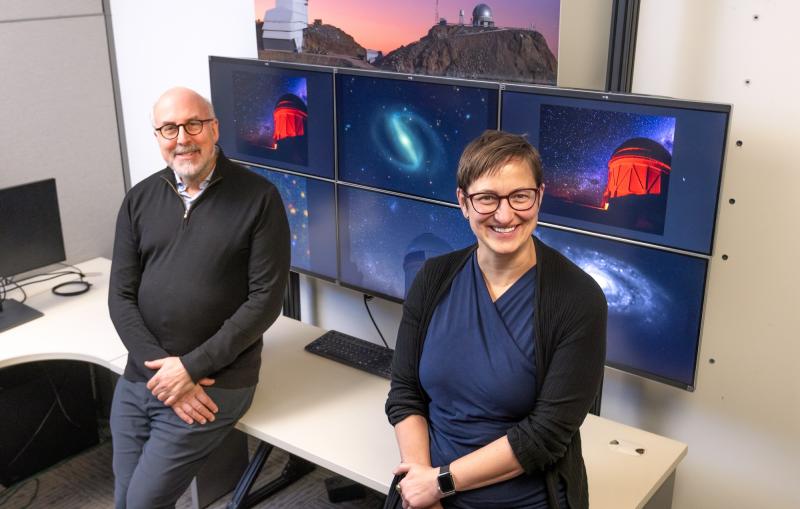

Gregg Thayer, a scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is the person in charge of Rubin's data acquisition system, which handles this essential process. Here, he walks us through some of the key steps.

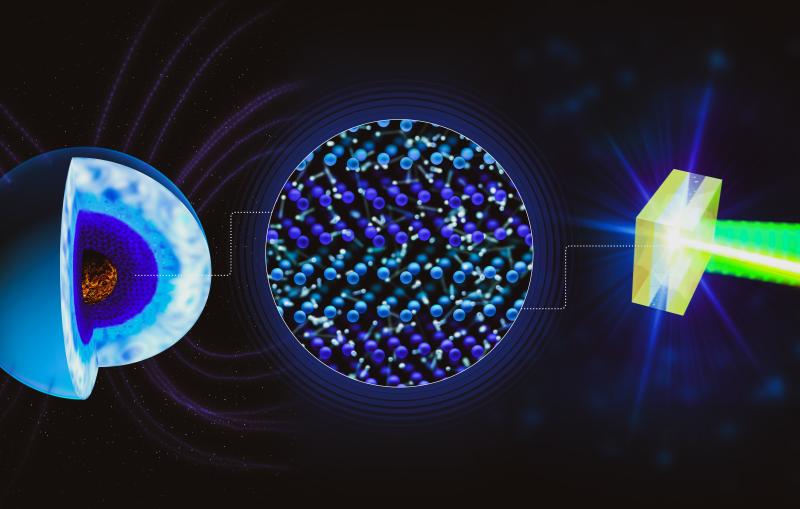

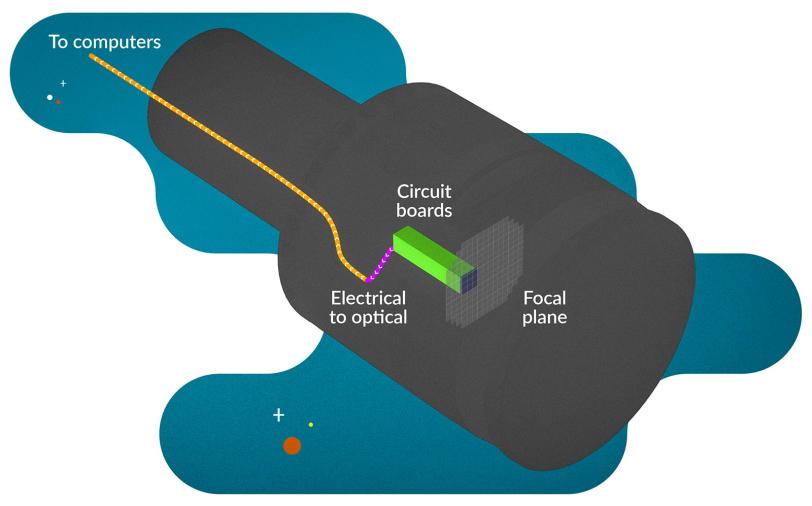

The data acquisition system starts right at the back of the focal plane, a composite of 189 digital sensors used to take night-sky images, plus several more used to line up the camera when taking images. 71 circuit boards take the raw pixels off the sensors and ready them for the next step.

At this point, two things need to happen. First, the data needs to get out of the cryostat, a high-vacuum, low-temperature and, Thayer says, "jam-packed" cavity that houses the focal plane and the surrounding electronics. Second, the data needs to be converted into optical signals for the fibers that go to the base of the camera.

Because there's so little space inside the cryostat, Thayer and his team decided to combine the steps: Electrical signals first enter circuit boards that penetrate the back of the cryostat. Those circuit boards convert the data to optical signals that are fed into fiber optic cables just outside the cryostat.

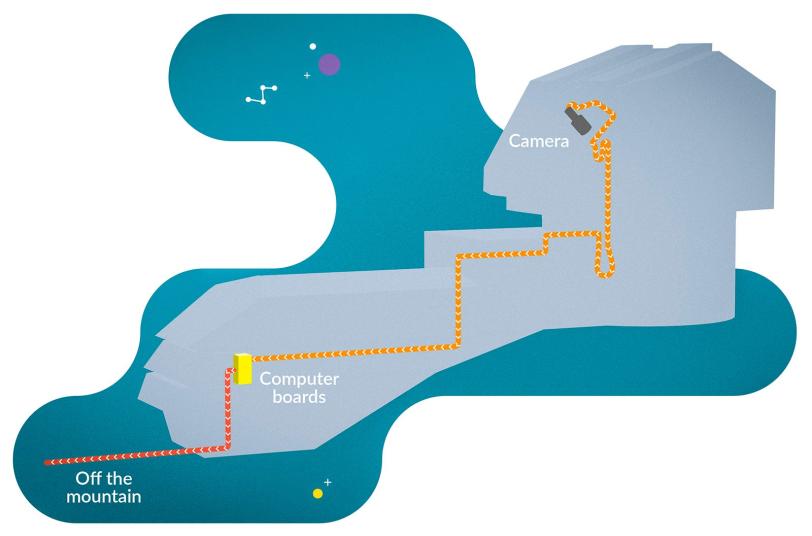

Why fiber optics? Data inevitably fades into noise if you go far enough along a signal cable, and the cable here has to be long – around 150 meters, or 500 feet, to make it from the top of the telescope to the base. The problem is compounded by a three gigabit per second data rate, around a hundred times faster than standard internet; low power at the source to reduce heat near the digital camera sensors; and mechanical constraints, such as tight bends, that require cable interconnects where more signal is lost. Thayer says that copper wires designed for electrical signals, can't transmit data fast enough over the distances required, and even if they could, they're too big and heavy to meet the mechanical demands of the system.

Once the signal makes it down from the camera, it feeds into 14 computer boards developed at SLAC as part of a general-purpose data acquisition system. Each board is equipped with eight on-board processing modules and 10 gigabit-per-second ethernet switches that connect the boards together. (Each board also converts the optical signals back to electrical ones.) Three of those boards read out the data from the camera and prepare it to be sent down the mountain and out to the U.S. data facility at SLAC and another in Europe. Three more emulate the camera itself – essentially, they allow researchers working on the project to practice taking data, perform diagnostics, and so on when the camera itself is unavailable, Thayer says.

Contact

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.