First realistic portraits of squishy layer that’s key to battery performance

Cryo-EM snapshots of the solid-electrolyte interphase, or SEI, reveal its natural swollen state and offer a new approach to lithium-metal battery design.

By Glennda Chui

Lithium metal batteries could store much more charge in a given space than today’s lithium-ion batteries, and the race is on to develop them for next-gen electric vehicles, electronics and other uses.

But one of the hurdles that stand in the way is a silent battle between two of the battery’s parts. The liquid between the battery electrodes, known as the electrolyte, corrodes the surface of the lithium metal anode, coating it in a thin layer of gunk called the solid-electrolyte interphase, or SEI.

Although formation of SEI is believed to be inevitable, researchers hope to stabilize and control the growth of this layer in a way that maximizes the battery’s performance. But until now they have never had a clear picture of what the SEI looks like when it’s saturated with electrolyte, as it would be in a working battery.

Now, researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have made the first high-res images of this layer in its natural plump, squishy state. This advance was made possible by cryogenic electron microscopy, or cryo-EM, a revolutionary technology that reveals details as small as atoms.

The results, they said, suggest that the right electrolyte can minimize the swelling and improve the battery’s performance – giving scientists a potential new way to tweak and improve battery design. They also give researchers a new tool for studying batteries in their everyday working environments.

The team described their work in a paper published in Science today.

“There are no other technologies that can look at this interface between the electrode and the electrolyte with such high resolution,” said Zewen Zhang, a Stanford PhD student who led the experiments with SLAC and Stanford professors Yi Cui and Wah Chiu. “We wanted to prove that we could image the interface at these previously inaccessible scales and see the pristine, native state of these materials as they are in batteries.”

Cui added, “We find this swelling is almost universal. Its effects have not been widely appreciated by the battery research community before, but we found that it has a significant impact on battery performance.”

A ‘thrilling’ tool for energy research

This is the latest in a series of groundbreaking results over the past five years that show cryo-EM, which was developed as a tool for biology, opens “thrilling opportunities” in energy research, the team wrote in a separate review of the field published in July in Accounts of Chemical Research.

Cryo-EM is a form of electron microscopy, which uses electrons rather than light to observe the world of the very small. By flash-freezing their samples into a clear, glassy state, scientists can look at the cellular machines that carry out life’s functions in their natural state and at atomic resolution. Recent improvements in cryo-EM have transformed it into a highly sought method for revealing biological structure in unprecedented detail, and three scientists were awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in chemistry for their pioneering contributions to its development.

Inspired by many success stories in biological cryo-EM, Cui teamed up with Chiu to explore whether cryo-EM could be as useful a tool for studying energy-related materials as it was for studying living systems.

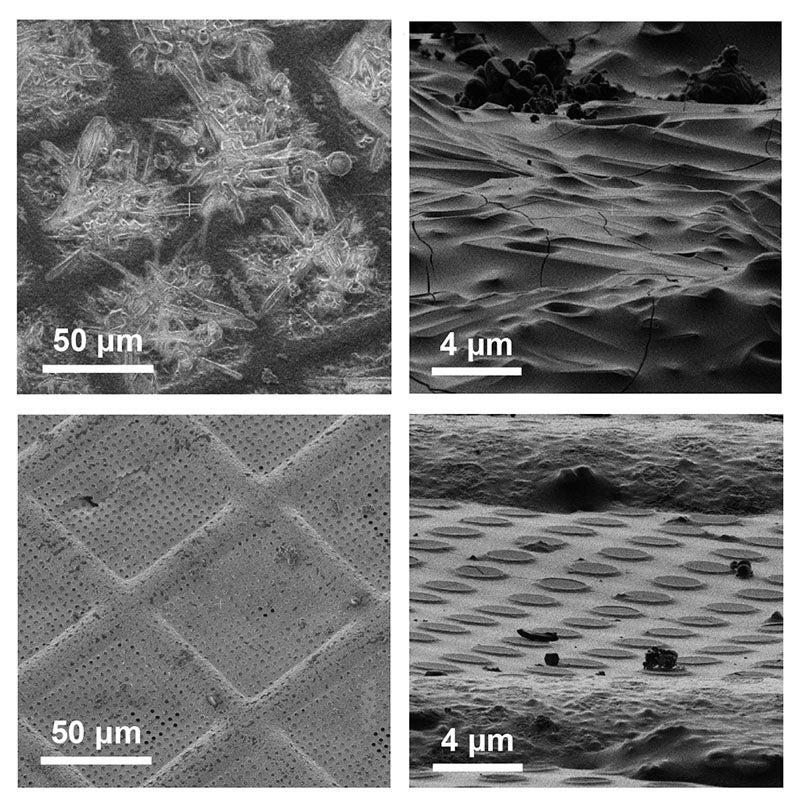

One of the first things they looked at was one of those pesky SEI layers on a battery electrode. They published the first atomic-scale images of this layer in 2017, along with images of finger-like growths of lithium wire that can puncture the barrier between the two halves of the battery and cause short circuits or fires.

But to make those images they had to take the battery parts out of the electrolyte, so that the SEI dried into a shrunken state. What it looked like in a wet state inside a working battery was anyone’s guess.

Blotter paper to the rescue

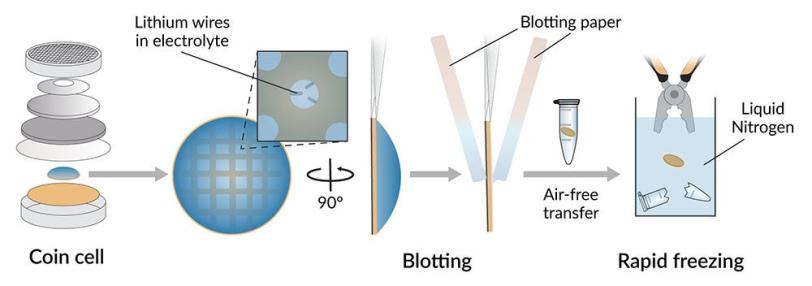

To capture the SEI in its soggy native environment, the researchers came up with a way to make and freeze very thin films of the electrolyte liquid that contained tiny lithium metal wires, which offered a surface for corrosion and the formation of SEI.

First, they inserted a metal grid used for holding cryo-EM samples into a coin cell battery. When they removed it, thin films of electrolyte clung to tiny circular holes within the grid, held in place by surface tension just long enough to perform the remaining steps.

However, those films were still too thick for the electron beam to penetrate and produce sharp images. So Chiu suggested a fix: sopping up the excess liquid with blotter paper. The blotted grid was immediately plunged into liquid nitrogen to freeze the little films into a glassy state that perfectly preserved the SEI. All this took place in a closed system that protected the films from exposure to air.

The results were dramatic, Zhang said. In these wet environments, SEIs absorbed electrolyte and swelled to about twice their previous thickness.

When the team repeated the process with half a dozen other electrolytes of varying chemical compositions, they found that some produced much thicker SEI layers than others – and that the layers that swelled the most were associated with the worst battery performance.

“Right now that connection between SEI swelling behavior and performance applies to lithium metal anodes,” Zhang said, “but we think it should apply as a general rule to other metallic anodes, as well.”

The team also used the super-fine tip of an atomic force microscope (AFM) to probe the surfaces of SEI layers and verify that they were more squishy in their wet, swollen state than in their dry state.

In the years since the 2017 paper revealed what cryo-EM can do for energy materials, it’s been used to zoom in on materials for solar cells and cage-like molecules called metal-organic frameworks that can be used in fuel cells, catalysis and gas storage.

As far as next steps, the researchers say they’d like to find a way to image these materials in 3D – and to image them while they’re still inside a working battery, for the most realistic picture yet.

Yi Cui is director of Stanford’s Precourt Institute for Energy and an investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC. Wah Chiu is co-director of the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Facilities, where the cryo-EM imaging work for this study took place. Part of this work was performed at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities (SNSF) and Stanford Nanofabrication Facility (SNF). The research was funded by the DOE Office of Science.

Citations:

Zewen Zhang et al., Science, 6 January 2022 (10.1126/science.abi8703)

Zewen Zhang et al., Accounts of Chemical Research, July 2021 (10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00183)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.