Researchers probe secrets of natural antibiotic assembly lines

In two new papers, researchers used X-ray crystallography and cryogenic electron microscopy to reveal new details of the structure and function of molecular assembly lines that produce common antibiotics.

Every cell is a master builder, able to craft useful and structurally complex molecules, time and again and with astonishingly few mistakes. Scientists are keen to replicate this feat to build their own molecular factories, but first they’ll need to understand it.

“We have thousands of these assembly lines in nature, and they all make unique compounds,” said Dillon Cogan, a postdoctoral scholar in the lab of Stanford chemist Chaitan Khosla. “The dream is to one day be able to recombine pieces from different assembly lines so that we can make useful compounds not found in nature. To do that, we need to know the design principles that make these things work.”

Now, two new studies from researchers at Stanford University, the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, the University of Texas, El Paso, and Cornell University have revealed more about how two such assembly lines maintain precise control.

Using some of the most sophisticated structural biology techniques available, Stanford researchers have learned more about how these molecule-making assembly lines maintains its precise control. The studies, published Nov. 5 in Science, reveal new details of how two such assembly lines propel growing molecules through the construction process.

The complex molecules in question are called polyketides, a category that includes drugs like statins and antibiotics like erythromycin. While cells synthesize polyketides with ease using assembly lines called synthases, their chemical complexity means chemists struggle to create them in the lab.

Each synthase can contain dozens of catalytic domains, the chemical stations along the assembly line that add pieces to and modify growing molecular chains.

Stopping the molecular wiggles

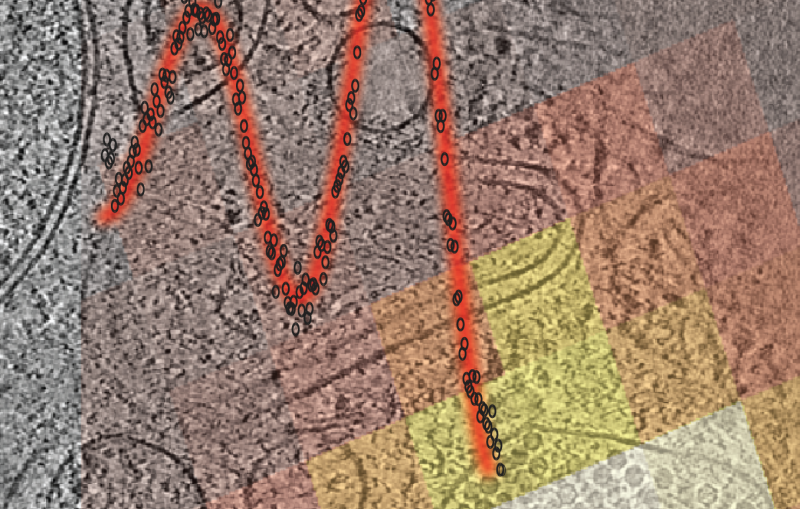

In one study, Khosla, Cogan and colleagues focused on a module from the assembly line that produces the antibiotic erythromycin. They wanted to see the molecule in many different shapes, each one corresponding to a stage in the assembly-line process. To do so, they turned to SLAC and Stanford professor Wah Chiu, an expert in cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), a technique that images wiggling molecules frozen in place, allowing researchers to see them in many different forms at once.

Chiu was instantly intrigued. “These are amazingly complex molecular machines. There are so many components that have to come together at the right place and the right time, in a highly orchestrated way,” Chiu said.

Cogan partnered with Kaiming Zhang, a former postdoctoral scholar in Chiu’s group, to study their assembly line module at SLAC’s Stanford-SLAC Cryo-Electron Microscopy facility.

After many of years of work, they got a glimpse of something unexpected: Each module is made up of pairs of enzymes, and one of these pairs is two molecular arms that extend out from the sides. These arms were thought to mirror one another in their poses. But in the module Zhang and Cogan examined, one arm extended out while the second arm flexed downward.

The scientists soon realized that the structure they were observing was actually the module in action.

The flexed arm appeared to be operating like the arm of a turnstile, keeping incoming molecules waiting until the module releases the one it is working on. The pent-up energy of the flexed arm may also help to propel the molecule to the next stage of the assembly line.

X-rays and cryo-EM working together

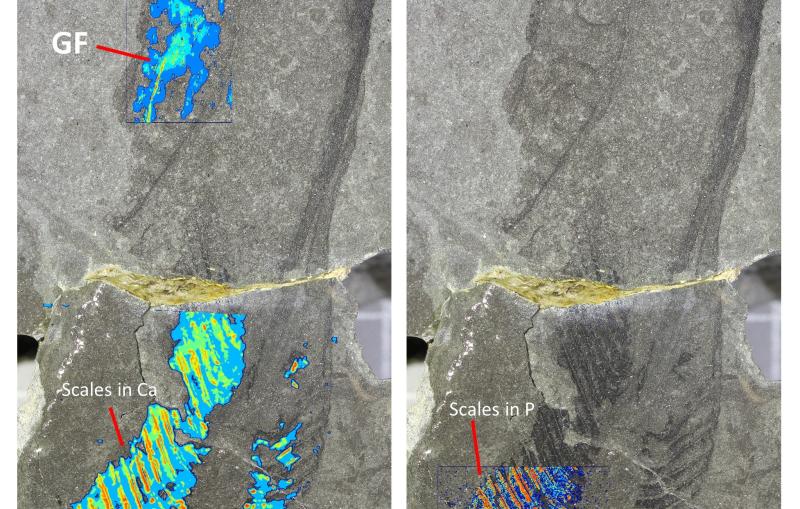

In a second study, University of Texas at El Paso, chemist Chu-Young Kim, SLAC scientist Irimpan Mathews, and Christopher Fromme from Cornell University examined one of the assembly line molecules responsible for building lasalocid A, a molecule produced by the bacterium Streptomyces lasalocidi and used as a veterinary antibiotic.

As with the Khosla lab’s study, Kim and colleagues wanted to better understand how the bacteria’s assembly line worked so that new drugs can be produced using engineered synthases.

But getting high-resolution images of an assembly line module, known as Lsd14, has been a major challenge, Mathews said. Lsd14 is very large, with 8 different locations along the assembly line module that add pieces to the final product. This makes it relatively susceptible to breaking apart before researchers can study it. Its size and flexibility also make high-resolution studies with X-ray crystallography especially difficult because it is hard to crystallize.

Mathews and Saket Bagde, a graduate student in Kim’s lab, joined the effort in 2017 and have been working since then to overcome those challenges and more. In the end, the team conducted X-ray studies at three facilities and made use of five different beamlines at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) before collecting enough good data to reach their conclusions.

The results came as a surprise. When first discovered, Kim said, scientists had thought Lsd14 – and other such modules – looked like a series of beads on a flexible string, and that the molecule under construction hopped along this structure as it was being built.

“That’s not the case at all,” Kim said. Instead, X-ray crystallography revealed Lsd14 is an elaborate, highly organized and compact protein. “That’s why previous attempts to engineer the protein frequently failed,” he said.

To augment their results, the team also performed cryo-EM studies at Cornell University to see what Lsd14 looked like in different stages in its assembly process that had proven too resistant to crystallization to study with X-rays. These studies showed the Lsd14 in different shape forms. Combining both techniques yielded information that might not have otherwise been available. “Our work is a beautiful example of how X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM produce complementary structural information,” Mathews said.

Kim said that having similar results from two different labs working on similar molecules lends support to the idea that the results may extend to other assembly-line molecules as well. Still, there’s a lot of work to do before researchers can start engineering their own molecular assembly lines in the most informed way. For one thing, the teams haven’t studied the entire assembly process of building either erythromycin or lasalocid A. The team needs to understand more about those processes, Kim said, “but this is a good start.”

Note: this article is based on press releases from Stanford University and Cornell University.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility. The Structural Molecular Biology Program at SSRL is supported by the DOE Office of Science and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Citations:

Cogan et al., Science, 5 November 2021 (10.1126/science.abi8358)

Bagde et al., Science, 5 November 2021 (10.1126/science.abi8532)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.