Researchers search uncharted waters to find a better data-storage material

Most new materials are discovered near the proverbial shore. Now, scientists deploy artificial intelligence and high-throughput experimental techniques to search previously uncharted waters to find revolutionary new materials.

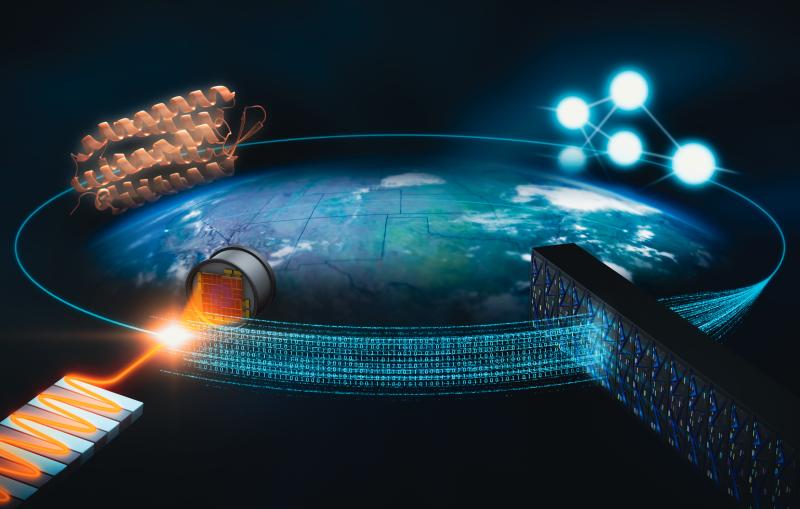

Whether it’s for batteries, computer memory or something else, most new materials are discovered by incrementally improving what we already know. But now, materials science researchers at the National Institute for Standards and Technology, the University of Maryland and the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have developed a way to search a much wider range of possibilities more efficiently than ever before, thereby accelerating the discovery of desired new materials.

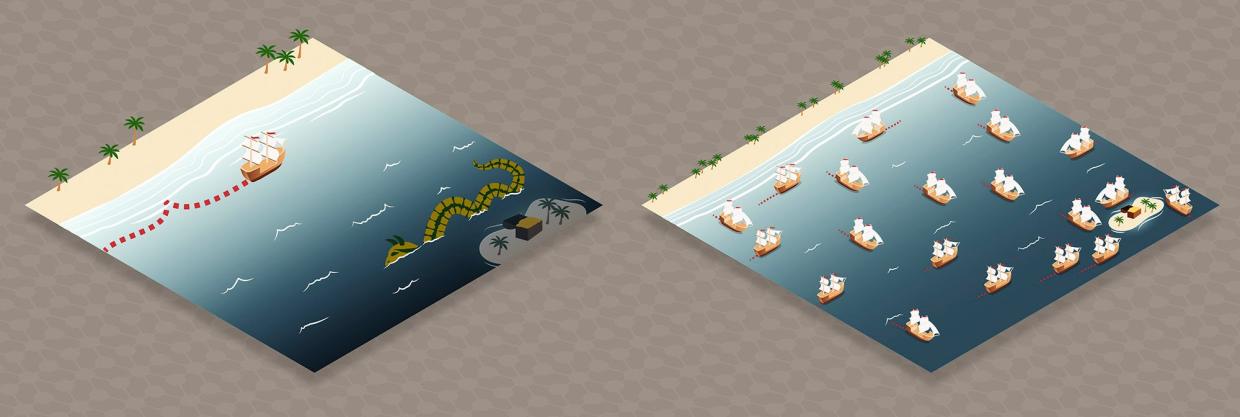

The new method – a combination of artificial intelligence and high-throughput experimental techniques – allows researchers to try out many possible materials essentially all at once and direct the search for the best ones more efficiently. Apurva Mehta, a staff scientist at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, puts in nautical terms: Where once researchers were sending a single ship sailing close to the shore to search for treasure, they can now launch a closely coordinated fleet of ships to sail across open ocean in their quest for treasure.

And, the researchers report November 24 in Nature Communications, the approach has already found at least a little bit of treasure, a new combination of germanium, antimony and tellurium that shows promise for energy-efficient data storage and next-generation computers.

Too many possibilities

Materials scientists constantly seek to discover new materials useful for specific applications – for example, a “metal that’s light but also strong for building a car, or a metal that can withstand high stresses and temperatures for a jet engine,” said NIST researcher Aaron Gilad Kusne.

But finding such new materials usually takes a large number of coordinated experiments and time-consuming theoretical work. For instance, a researcher interested in finding the best combination of even three or four atomic elements for a battery electrode might need to consider tens or hundreds of thousands of different combinations to find the right one. By brute force alone, Kusne said, that many experiments could take years or decades to complete.

That’s where the new technique, called CAMEO. comes in. Short for Closed-Loop Autonomous System for Materials Exploration and Optimization, CAMEO takes what researchers already know – including data from previous experiments and known materials science principles – to propose a set of new materials that may have improved properties.

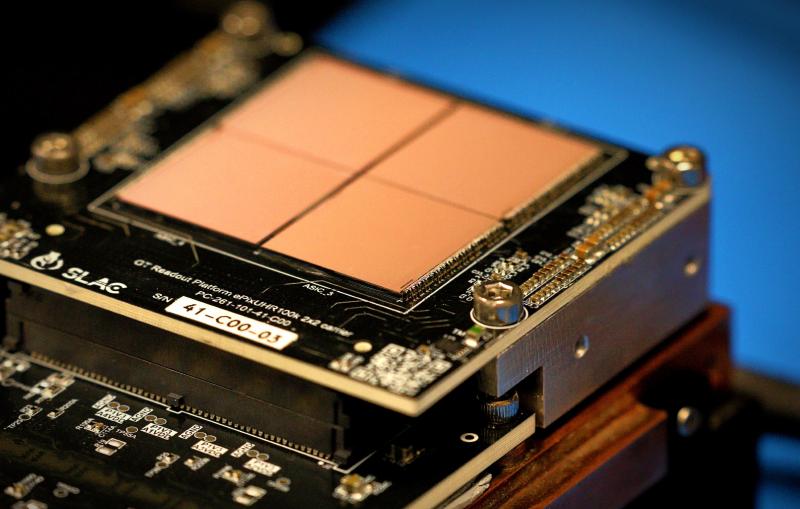

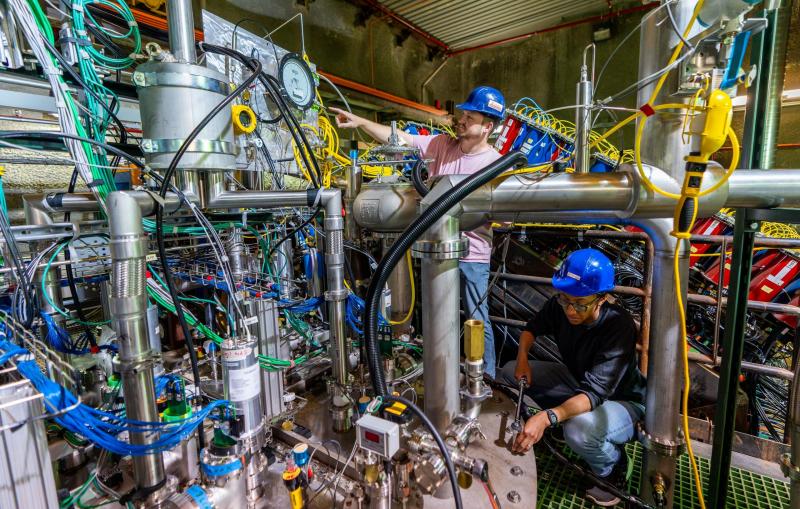

Then, it’s time to test out those materials. At SSRL’s Beam Line 1-5, a robotic system can perform X-ray tests on hundreds of samples arrayed on a plate in rapid succession, each test akin to a ship on the sea searching for treasure. Once a round of tests is complete, the data is fed back into CAMEO and the process starts again, with the algorithm picking a new set of materials to test – that is, data from the first ships is used to predict new spots on the ocean for other ships to search or avoid.

“The key to our study was that we were able to unleash CAMEO on a combinatorial library, where we had made a large array of materials all with different compositions,” said Ichiro Takeuchi, researcher and professor at University of Maryland. In a usual combinatorial study, every material in the array would have been measured one by one to look for the compound with the best properties. Even with a fast measurement setup, that takes a long time. With CAMEO, it only took a small fraction of those measurements to home in on the best material.

A new material

In the study, the team trained their sights on a mix of germanium, antimony and tellurium to find the best mix for materials commonly used in CDs and DVDs. These so-called phase-change memory materials store information by rapidly heating tiny bits of the material from a regular, crystalline state to a solid but amorphous one. The optical contrast between those states can be read by a laser as binary ones and zeros. The researchers’ aim, therefore, was for CAMEO to find the alloy with the largest optical contrast between the crystalline and amorphous states.

Starting with 177 potential combinations of the three elements, CAMEO performed 19 different experimental cycles to find an improved material, which had twice the contrast of a similar material in use today. Those tests took just 10 hours, compared to the estimated 90 hours it would have taken a scientist with the full set of 177 materials.

The new material, Ge4Sb6Te7, or GST467 for short, has applications for photonic switching devices, which control the direction of light in optical circuits. They can also be applied in a field of study focused on developing devices that emulate the structure and function of neurons in the brain, called neuromorphic computing, opening possibilities for new kinds of computers as well as other applications such as extracting useful data from complex images.

CAMEO’s future

One application of CAMEO is minimizing experimental costs. With AI running the measurements, collecting data and performing the analysis, researchers estimate the number of experiments performed can be cut by one tenth. It also reduces the amount of knowledge a researcher needs to run the experiment.

Another potential benefit is remote work for scientists. “This opens up the lab to a wave of scientists who can still be productive without actually being here,” Mehta said. Remote research involving contagious diseases or viruses, such as COVID-19, could be performed safely by relying on the AI to conduct the experiments in the lab.

For now, researchers will continue to improve the AI and try to make the algorithms capable of solving ever more complex problems. “CAMEO has the intelligence of a robot scientist, and it’s built to design, run, and learn from experiments in a very efficient way,” said Kusne.

The research was funded by grants from the Office of Naval Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiatives Program and the Semiconductor Research Corporation. Research at SSRL was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science.

Editor’s Note: This article is based on a press release from the National Institutes of Standards and Technology.

Citation: A. Gilad Kusne, Nature Communications, 24 November 2020 (10.1038/s41467-020-19597-w)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.