Identifying COVID-19 antibodies for potential treatments

Images reveal how some antibodies may block SARS-CoV-2 infection.

New research led by scientists at the California Institute of Technology and conducted in part at the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has identified mechanisms for how a number of antibodies neutralize SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The researchers hope that antibodies like the ones they describe in the new study can help treat or prevent COVID-19.

When someone gets an infection, their body can produce hundreds or even thousands of antibody variants in response. That leads to a wide diversity of antibodies in a single person and in the human population, and some antibodies are better at blocking, or neutralizing, a virus than others.

"An ideal treatment would be a cocktail of different antibodies that attack the virus in different, but still effective, ways," said Christopher Barnes, a Caltech senior postdoctoral fellow and the first author of the new paper, which was published in the journal Nature. "With a combination of antibodies, it's less likely that a virus can evolve to escape them."

Aina Cohen, a senior scientist at the SLAC synchrotron beamline where the Caltech team determined the antibody structures, said, “The knowledge they are uncovering, including how and where antibodies bind to the virus, could lead to new treatments for those at most risk from severe COVID-19, to enable more people to survive infection. It is a great feeling to work in the support and development of beamlines used for this caliber of biomedical research.”

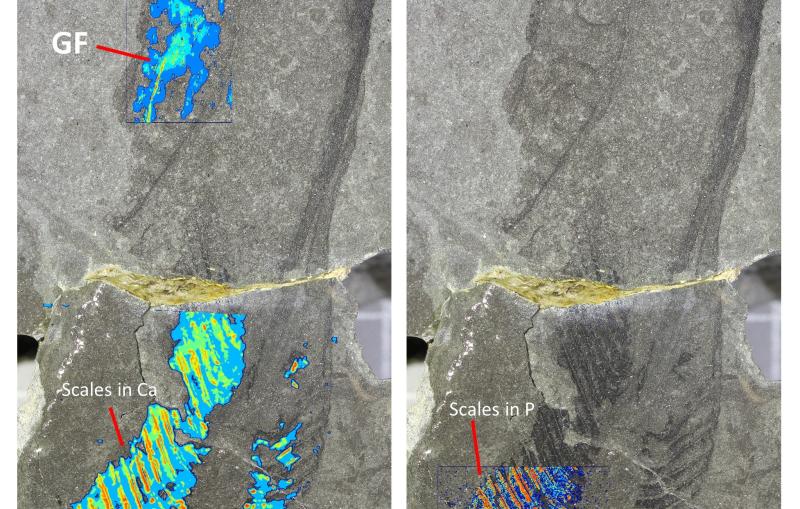

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Barnes and his adviser, structural biologist Pamela Björkman, have been studying the antibodies of people who have recovered from the disease, in search of the antibodies that are best at preventing SARS-CoV-2 from invading cells. Working at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and Caltech’s cryo-electron microscopy facilities, they imaged interactions between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and individual antibodies.

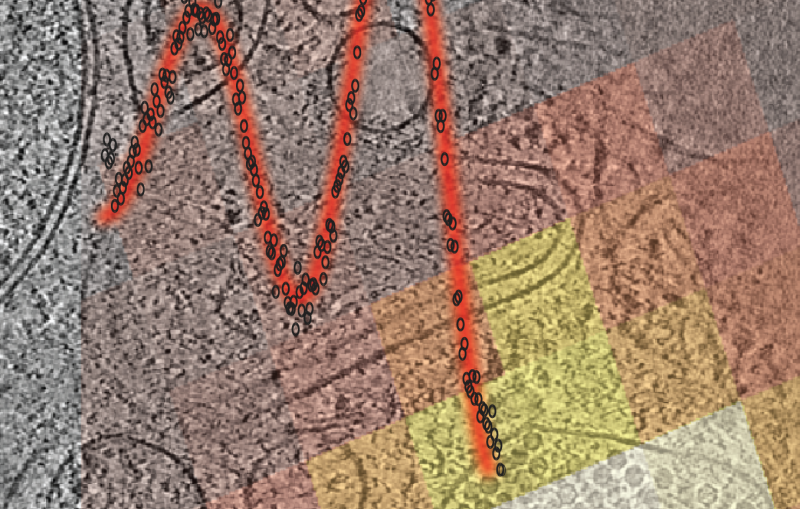

Barnes, Björkman and team focused in particular on a part of the virus’s outer layer called a receptor-binding domain, or RBD, at the tips of the coronavirus’s namesake spikes. Those RBDs grab onto cells and initiate infection by binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a molecule that regulates blood pressure. An antibody that could keep the virus from grabbing on at this site could therefore be very effective in preventing the virus from entering cells.

In a previous paper, the Caltech team collaborated with the laboratory of Michel Nussenzweig at The Rockefeller University to study antibodies collected from people who had recovered from COVID-19. Using electron microscopy techniques, they discovered where antibodies from COVID-19 convalescent plasmas bound to SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins.

In their latest paper, Barnes worked with Björkman lab graduate students, microscopists from other Caltech labs, and scientists at SSRL to reveal the molecular structures of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. From analyses of these structures, the team proposed four classes of anti-RBD antibodies based on which RBD sites they bound to, whether their binding overlapped with the ACE2 binding site and other criteria. From that classification, the researchers proposed several potential ways to neutralize the virus.

For example, they found a particularly interesting antibody that binds simultaneously to adjacent RBDs, clamping three RBDs into positions that would lock the spike into a conformation that cannot grab onto the ACE2 receptor site.

The team’s results will help researchers make better choices about which antibodies to use to treat COVID-19 or prevent infection in people in high-risk groups, Björkman said. "In addition, knowing the structures of these antibodies can facilitate the design of antibodies that bind more tightly to RBDs, thereby increasing their efficacy and lowering the dose needed for treatment,” she said. “And finally, mapping where these antibodies bind is necessary information for structure-based design of vaccines to elicit the most potent classes of neutralizing antibodies."

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Caltech Merkin Institute for Translational Research, and a George Mason University Fast Grant. Extraordinary SSRL operations were supported in part by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act. SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility. The Structural Molecular Biology Program at SSRL is supported by the DOE Office of Science and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Editor’s Note: This article is based on a press release from the California Institute of Technology.

Citation: Christopher Barnes, et al., Nature, October 12, 2020 (DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2852-1)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

Image credit: Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, from a 3D model created by the Visual & Medical Arts Unit and the Electron Microscopy Unit, Research Technologies Branch, Rocky Mountain Labs, NIAID (2020)

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.