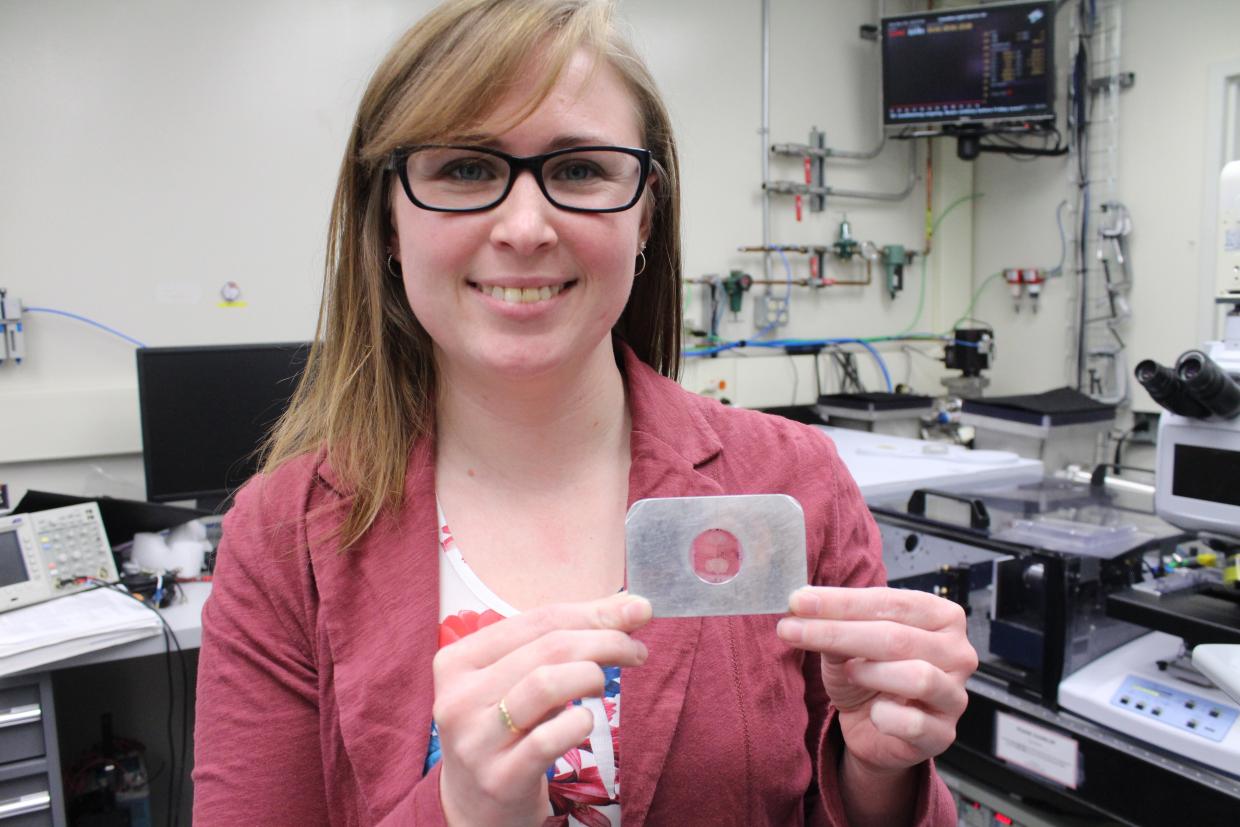

Kelly Summers wins 2020 Klein Award for research on treatments for Alzheimer’s disease

Using SLAC’s synchrotron, Summers improves fundamental knowledge of the role of copper in the brain and investigates treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

By Caitlyn Buongiorno

Kelly L. Summers, a PhD student from the University of Saskatchewan, became interested in the important roles that metals play in the body during her third year of undergraduate school. For instance, she points out, iron is crucial in helping to bind oxygen in blood. Currently, her research focuses on investigating the role copper plays in Alzheimer’s disease using the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

“It was a project presented to me when I was first starting my PhD, and the potential impact really spoke to me,” Summers says. “Every time I’ve presented this work, there’s always been someone who comes up to me afterwards and mentions how they or someone they know have been impacted by the disease.”

Summers has been selected to receive the 2020 Melvin P. Klein Scientific Development Award for her research on not only the role of copper in the brain, but also potential candidate drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

“I was very surprised and excited, and obviously very honored, to be receiving this prize from SSRL, where I’ve spent a lot of my time during my PhD,” Summers says. “It will help me as I move into the next phase of my career.”

Basic insights into brain chemistry

In a recommendation letter, Summers’ PhD advisor, Graham George, made note of other ways her work at SSRL has been recognized, pointing out that she won the SSRL Joe Wong Outstanding Poster Award, becoming the first student to do so twice, for neurodegenerative disease research in 2018 and cancer research in 2019. “Such diverse subjects have become a hallmark of her research approach,” he said.

Summers also was chosen to represent the element copper in last year’s International Year of the Periodic Table celebration hosted by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

Hugh Harris, head of the chemistry department at Australia’s University of Adelaide, highlighted the strides her work has made in understanding Alzheimer’s disease in his own recommendation letter. Her work, he said, “has provided critical insight into the basic chemistry that controls the disease” and was especially crucial in regard to potential treatments.

One step forward

Summers says that the exact role of copper in the brain and how it contributes to the disease is still not well understood. Alzheimer’s disease appears to cause key proteins in the brain to form improperly when binding with metals. Once tangled in the protein ‘plaques’, these metals, including copper, are inhibited from performing their duties.

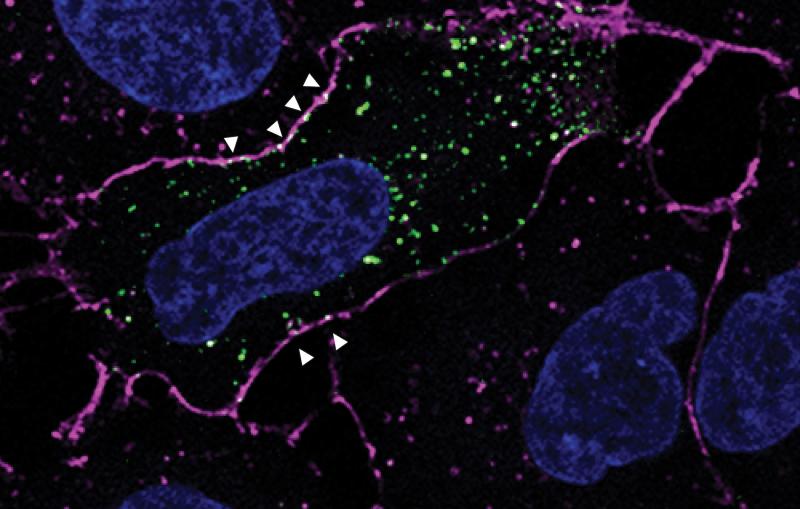

Summers looked at one of the brain’s essential proteins, amyloid beta (Aβ), to get a better grasp of how the disease affects the brain.

During Alzheimer’s, the amyloid beta protein – along with a handful of other proteins – forms clusters or plaques, tying up crucial metals such as copper. Copper is essential to the brain, but in higher concentrations can be toxic because of reactions with oxygen that can damage neuronal pathways. This means that aggregated proteins, which can clump copper, are a huge detriment to someone with Alzheimer’s.

That’s where potential treatments can come in. Summers looked at a chemical compound, known as 8-hydroxyquinoline (8-HQ), and how it interacts with copper in the brain. “It’s an interesting compound because there is an opportunity to change it a little bit,” Summers says. “We can potentially control how it binds to a metal like copper.”

Summers blasted samples of mouse brain tissue – which form similar amyloid plaques with copper that are seen in human brains – with X-rays from SSRL. This allowed her to see how two weeks of treatment with 8-HQ changed the levels of amyloid beta and copper in the tissue. While little is understood about how 8-HQ works in the brain, the research seems to indicate that it can slide into the tangled protein and remove the copper trapped inside. The copper then has less of a chance of producing toxins when bound by 8-HQ.

Summers is excited by the results but acknowledges that there is still a lot of work ahead. “We’ve taken one small step forward in understanding how copper acts in the brain,” she says. Although she will be moving on to other areas of investigation, she says, “Hopefully, someone will be able to continue my research and take it another step.”

Summers will receive the award and give a presentation at the annual SSRL/LCLS Users’ Meeting. To hear this talk or participate in other sessions, register online before Sept. 25.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.