How iron transforms under pressure

New research could offer insights into the formation of planets like Earth and inform the design of more resilient materials.

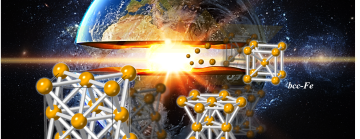

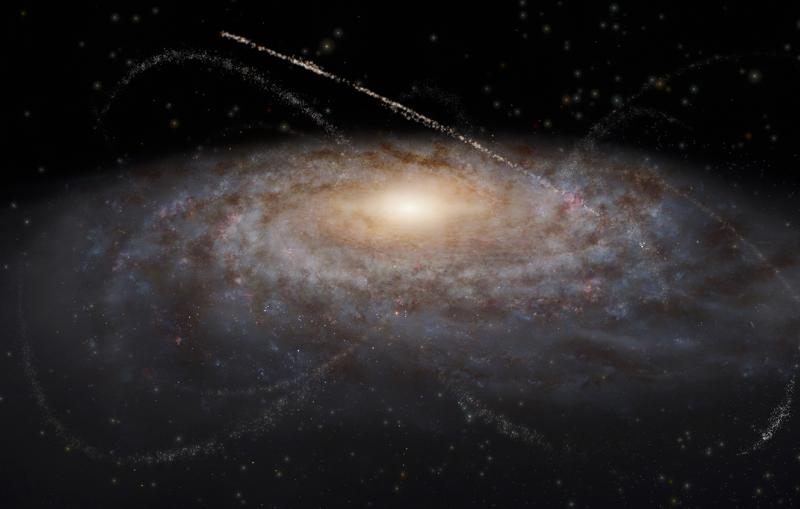

Iron is the most abundant metal in the universe. It forms the complex structure at Earth’s core, producing a planetary magnetic field that protects life on its surface from space radiation.

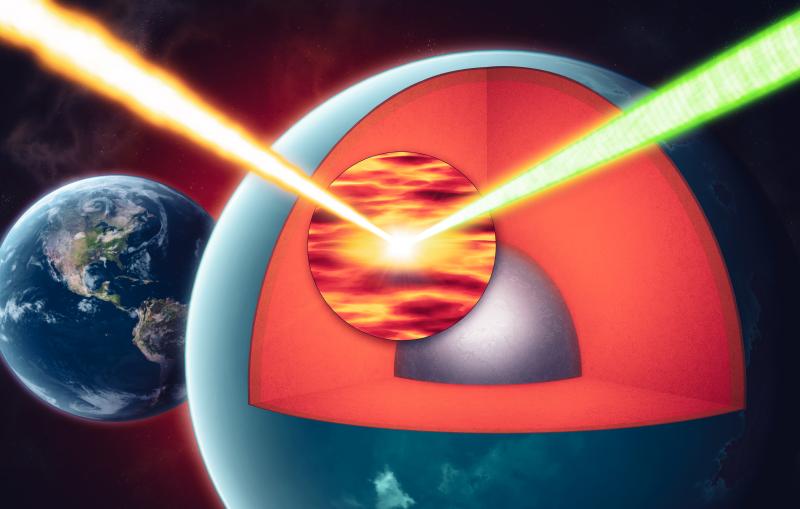

To understand how iron and other materials act in the extreme conditions of planetary cores, scientists use powerful laser beam pulses to launch a shockwave into a material and increase its pressure and temperature.

Now, an international team of scientists has observed how the structure of iron changes during a rapid impact produced by a laser pulse. The way iron atoms rearrange in response to this extreme shock offers new insights into the formation of planets like Earth and could inform the design of more resilient materials. The team, led by Yongjae Lee, a scientist at Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea, and scientists Eric Galtier and Hae Ja Lee at the Department of Energy’s (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, published their results in Science Advances earlier this month.

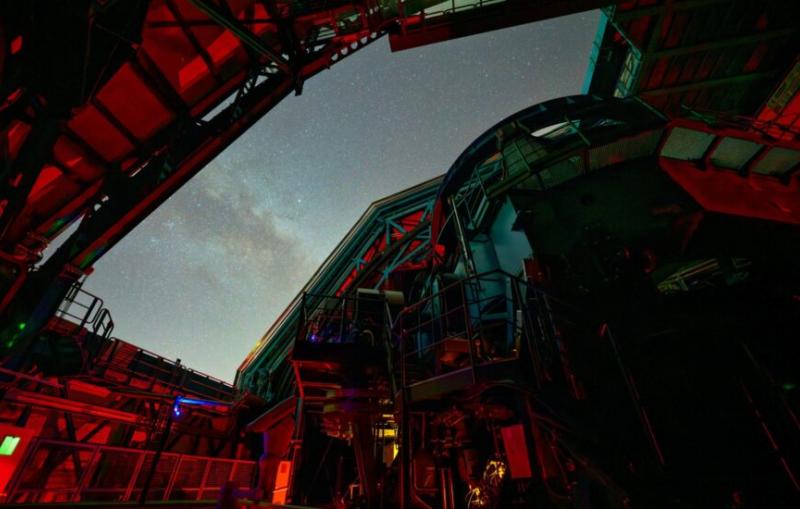

In experiments at PAL-XFEL, located in Pohang, South Korea, the researchers blasted an iron sample with a laser pulse that lasted for just a few hundred picoseconds, or trillionths of a second, producing a force that rivals that of a meteorite crashing into Earth’s surface. The material was then probed with a shorter femtosecond, or a millionth of a billionth of a second, X-ray pulse to see how the iron’s atoms rearranged in response to the shock. The X-ray probe duration is so short that it can take snapshots of the material conditions as the shock moves through it. This allowed the researchers to string together a stop motion movie of how the iron cristalline structure deforms on impact.

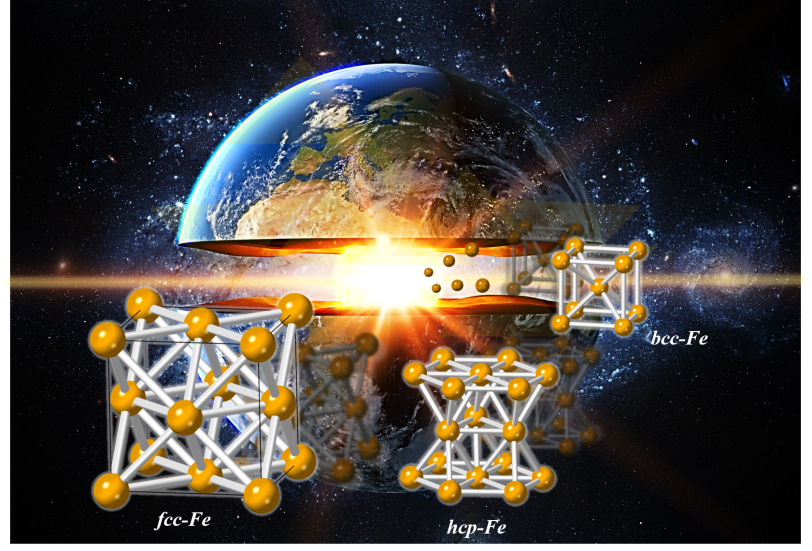

Usually, iron atoms are arranged with one atom at the center of a cube and at each vertex. At high enough temperatures, the iron maintains this cubic arrangement with iron atoms at each vertex, but rather than one iron atom in the center there is an iron atom at each of the six cube faces. At high enough pressures, the arrangement of iron atoms transforms from a cube into a hexagonal pattern. In response to the high temperatures and pressures achieved in this experiment, the researchers watched the iron evolve through each of these atomic arrangements. Next, they plan to use this technique at different temperatures and pressures on iron and other materials to better understand how they behave during the rapid energy changes induced by the shockwave.

The team also included researchers from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; Arizona State University; the University of South Carolina; Pohang Accelerator Laboratory and the Korea Polar Research Institute in South Korea; the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research in China; and Osaka University in Japan. This work was supported by the Leader Researcher program of the Korean Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (MSIP), the National Nuclear Security Administration, and DOE’s Office of Science.

Citation: H. Hwang et al., Science Advances, 5 June 2020 (10.1126/sciadv.aaz5132)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.