In a first, researchers identify reddish coloring in an ancient fossil – a 3-million-year-old mouse

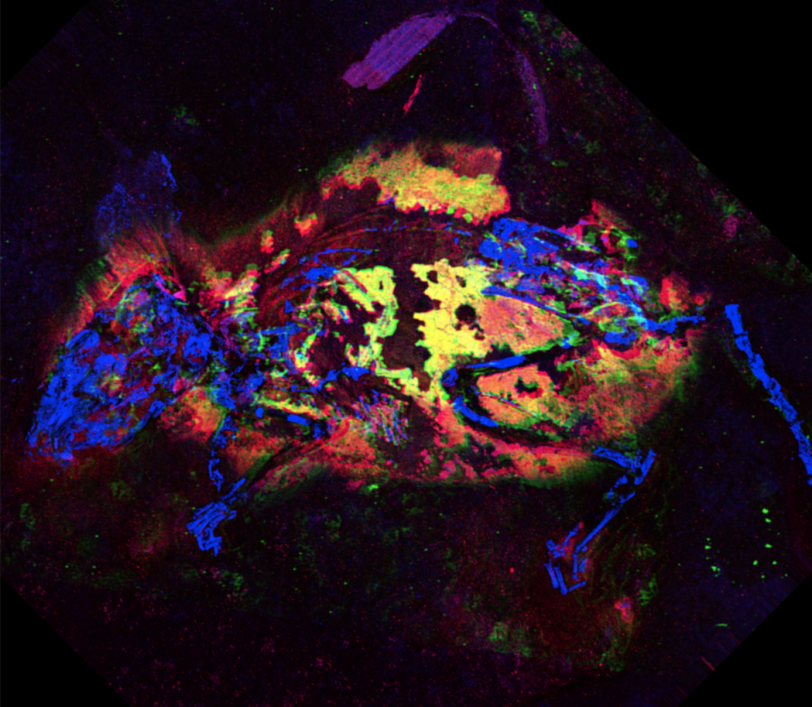

X-rays reveal an extinct mouse was dressed in brown to reddish fur on its back and sides and had a tiny white tummy.

Menlo Park, Calif. — Researchers have for the first time detected chemical traces of red pigment in an ancient fossil – an exceptionally well-preserved mouse, not unlike today’s field mice, that roamed the fields of what is now the German village of Willershausen around 3 million years ago.

The study revealed that the extinct creature, affectionately nicknamed “mighty mouse” by the authors, was dressed in brown to reddish fur on its back and sides and had a tiny white tummy. The results were published today in Nature Communications.

The international collaboration, led by researchers at the University of Manchester in the U.K., used X-ray spectroscopy and multiple imaging techniques to detect the delicate chemical signature of pigments in this long-extinct mouse.

“Life on Earth has littered the fossil record with a wealth of information that has only recently been accessible to science,” says Phil Manning, a professor at Manchester who co-led the study. “A suite of new imaging techniques can now be deployed, which permit us to peer deep into the chemical history of a fossil organism and the processes that preserved its tissues. Where once we saw simply minerals, now we gently unpick the ‘biochemical ghosts’ of long extinct species.”

The research team, which includes scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, used X-ray beams from SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and the Diamond Light Source (DLS) in the U.K.

Painting a picture of the past

Color plays a vital role in the selective processes that have steered evolution for hundreds of millions of years. But until recently, techniques used to study fossils weren’t capable of exploring the pigmentation of ancient animals, which is pivotal when reconstructing what they looked like.

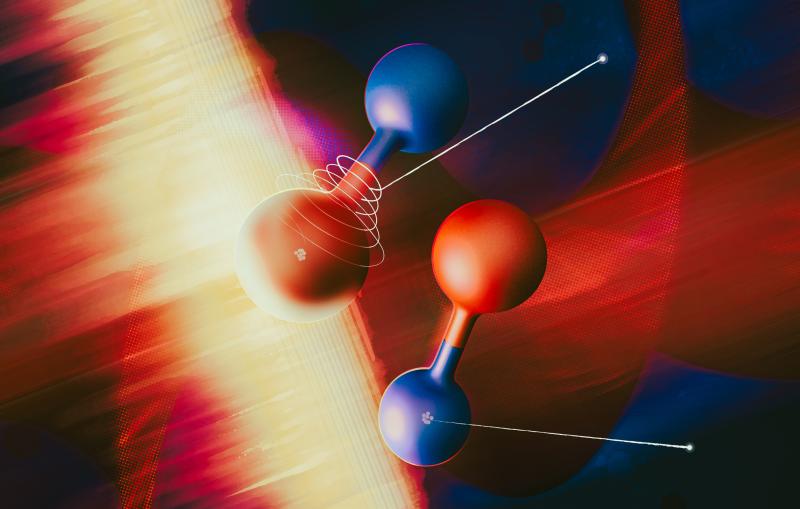

This most recent paper marks a breakthrough in the ability to resolve fossilized color pigments in long-gone species by mapping key elements associated with the pigment melanin, the dominant pigment in animals. In the form of eumelanin, the pigment gives a black or dark brown color, but in the form of pheomelanin, it produces a reddish or yellow color.

Building the foundation

Until recently, the researchers had focused on the traces of elements known to be associated with eumelanin, which in previous experiments revealed dark and light patterns in the feathers of the first birds, including Archaeopteryx, the famous fossil that first offered a clear link between dinosaurs and birds.

In 2016, co-author Nick Edwards, scientist at SLAC, led a study that demonstrated the potential to differentiate between eumelanin and pheomelanin in modern bird feathers. That work provided a chemical benchmark for this most recent paper, which for the first time showed it’s possible to detect the elusive red pigment, which is far less stable over geological time, in ancient fossils.

“We had to build up a strong foundation using modern animal tissue before we could apply the technique to these ancient animals,” Edwards said. “It was really a tipping point in using chemical signatures to crack the coloring of ancient animals with soft tissue fossils.”

To reveal the fossil patterns in the mighty mouse, the Manchester team used SSRL and DLS to bathe the fossils in intense X-rays. The interaction of those X-rays with trace metals found in pigments allowed the team to reconstruct the reddish coloring in the mouse’s fur.

“The fossils used in this study preserve amazing structural detail, but our work emphasizes that such exceptional preservation may also lead to extraordinary chemical detail that changes our understanding of what is possible to resolve in fossils,” said Manchester professor of geochemistry Roy Wogelius, who co-led the study. “Along the way we learned so much more about the chemistry of pigmentation throughout the animal kingdom”

Adding a new dimension

The key to their work was determining that trace metals were incorporated into the fossilized mouse fur in exactly the same way that they bond to pigments in animals with high concentrations of red pigment in their tissue.

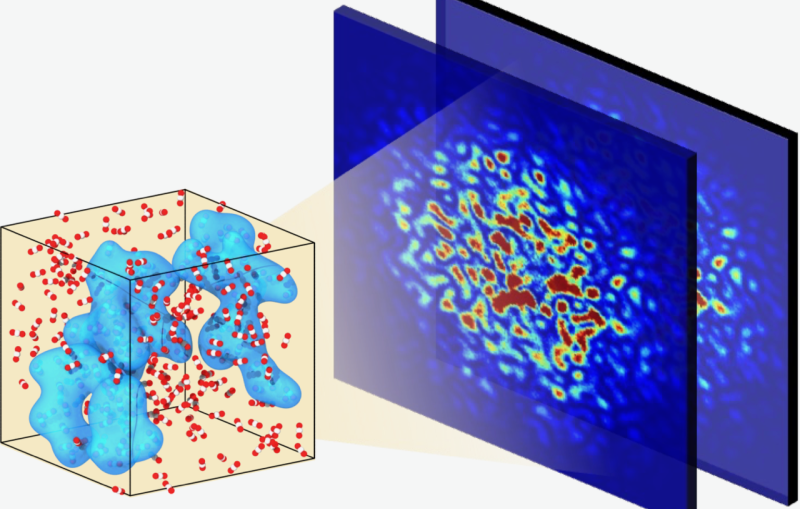

“As you do research in a particular area, the scope of your techniques might evolve,” says Uwe Bergmann, co-author and a distinguished staff scientist at SLAC who led the development of the X-ray fluorescence imaging used in this research. “The hope is that you can develop a tool that will become part of the standard arsenal when something new is studied, and I believe the application to fossils is a good example.”

The effort, which involved physics, paleontology, organic chemistry and geochemistry, informs the scientists what to look for in the future.

“Our hope is that these results will mean that we can become more confident in reconstructing extinct animals and thereby add another dimension to the study of evolution,” Wogelius says.

The team also included researchers from the Fujita Health University in Japan; the Stanford PULSE Institute; the College of Charleston in South Carolina; the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis; the University of Southampton in the U.K.; and the Joint Paleontology Foundation in Spain. The fossils were made available to the study by the University of Göttingen in Germany.

SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility. Funding was provided by the U.K. Natural Environment Research Council.

-Written by Ali Sundermier

Citation: P.L. Manning et al., Nature Communications, 21 May 2019 (10.1038/s41467-019-10087-20)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.