In brief: Probing battery hotspots for safer energy storage

A laser technique lets researchers see how potentially dangerous growths form in batteries.

By Erika K. Carlson

Researchers are striving to make tomorrow’s batteries charge faster and store more energy. But these conveniences come with safety challenges, like more heat produced in a battery. For the first time, a team of researchers has studied the effects of tiny areas within lithium metal batteries that are much hotter than their surroundings. These hotspots, the researchers find, can make batteries grow spiky tumors of metal called dendrites that could cause short circuits, and potentially lead to fires. The team of researchers, from Stanford University and the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, published their findings May 6 in Nature Communications.

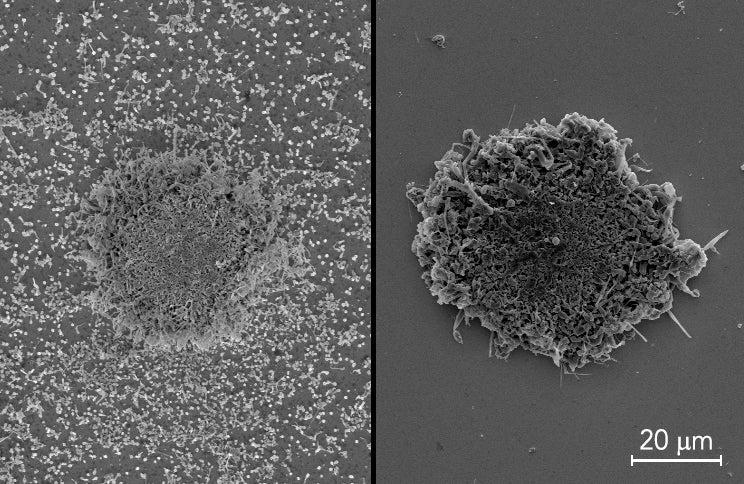

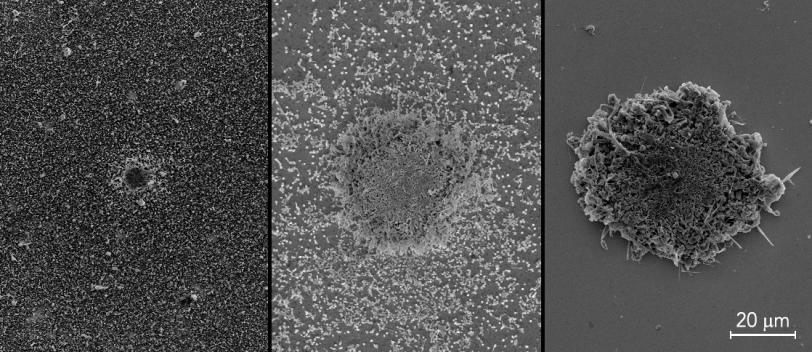

By shining lasers onto the batteries, the team created microscopic temperature hotspots on electrodes. When they looked at the electrodes with a scanning electron microscope, they saw that lithium metal inside the batteries piled up on hotspots much faster than on other areas of the electrodes. If they grow long enough, these dendrites could puncture the barriers that separate positive and negative sides of batteries, causing short circuits. Short circuits like these can cause runaway temperatures that might explain why some batteries explode or catch on fire.

The team hopes that their work will inspire other researchers to study batteries using this technique. It will be important to create ways to better manage batteries’ temperatures, they say, in the quest for higher energy and safer batteries.

Yangying Zhu, a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford University, and Jin Xie, a Stanford postdoc who is now a ShanghaiTech University assistant professor, were the study’s lead authors. Yi Cui, a professor at Stanford and SLAC, was the principal investigator. This work was supported by the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Part of the work was performed at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities and the Stanford Nanofabrication Facility.

Citation: Yangying Zhu et al., Nature Communications, 6 May 2019 (10.1038/s41467-019-09924-1)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.