Q&A: Simon Bare Catalyzes New Chemistry Effort at SLAC

After 30 Years in Industry, He’s Looking for Ways to Build on Research Strengths at SLAC and Stanford

Most people know catalysts as the things that break down noxious exhaust gases in a car’s catalytic converter. But their usefulness goes far beyond that, touching every aspect of modern life by making the chemical reactions used to manufacture fuel, fertilizer and other products more efficient.

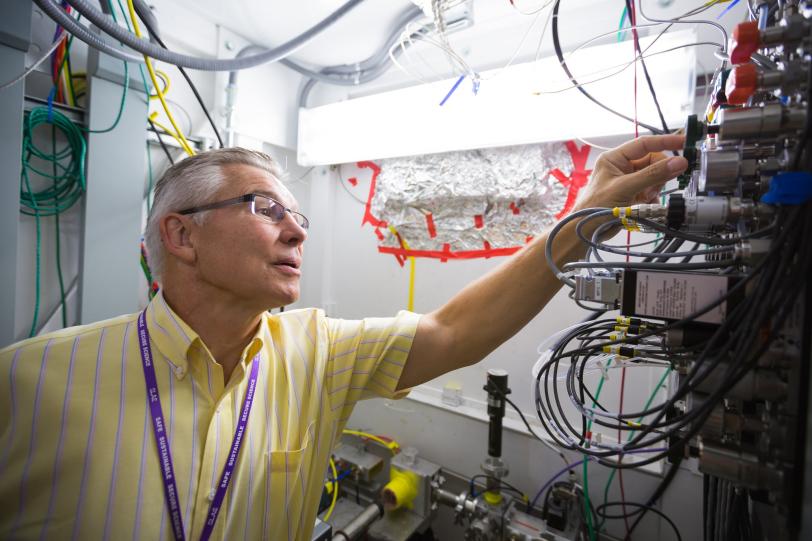

Simon Bare, who joined the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in April, spent 30 years as an industrial chemist investigating how catalysts work. Now, as co-director of the Chemistry and Catalysis Division at the lab’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), his goal is to build on research strengths at SLAC and Stanford University to create a West Coast center for catalyst research and define new research directions.

We talked with Bare about his career, his research and his new role.

What are catalysts, and why are they so important?

A catalyst is a substance that’s added to a chemical reaction to lower the activation energy for that reaction. So it takes a reaction that is incredibly slow and speeds it up to the point where it’s useful. The catalyst itself remains unchanged.

Basically we could not have the standard of life that we’re used to on this planet without catalysts. They’re used in the production of everything we touch, from fuels to plastics to pharmaceuticals. For instance, the production of ammonia for fertilizer, which allows us to grow the food we need, is carried out with catalysts and consumes about 1 percent of all the energy used on Earth.

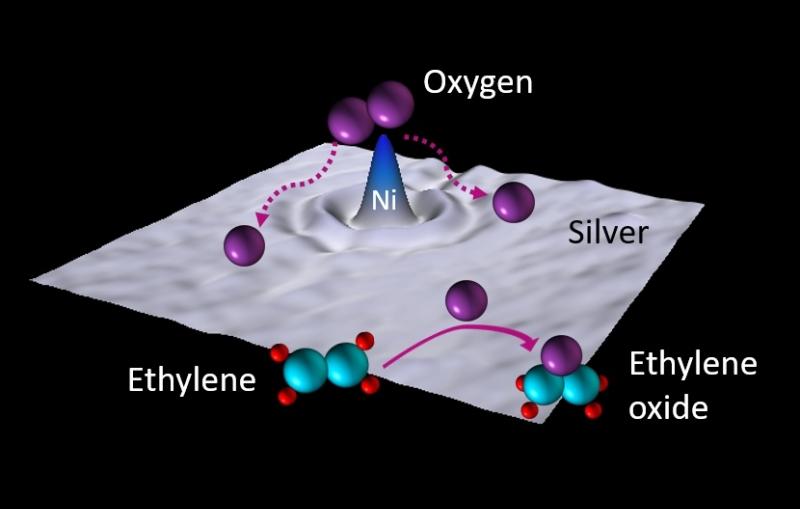

One of the Holy Grails is developing a catalyst to make useful products from carbon dioxide – so you start off with a gas that’s causing global climate change and end up with a sustainable fuel, for instance. This is the current focus of the DOE’s Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis, or JCAP, which SLAC and SSRL play a key role in.

How did you get into this area of science?

I’m from northeastern England, and I started off at the University of Liverpool. Initially I wanted to be a geographer. That was my passion in life, from human geography to the natural landscape and natural Earth processes like volcanism and earthquakes.

I was all set to do that when as an undergraduate I had the pleasure of working on a research project with Professor David King, who went on to Cambridge and later became science adviser to Tony Blair in the U.K. government. I remember him saying, “What are you going to do as a geographer? Teach geography? You’ve got to come work with me and study chemistry.”

So I did. I was fascinated by the methodology, the techniques, being able to go in and study things at the atomic level, being surrounded by big equipment – the physical aspect of that was always exciting to me.

I started my career at Dow Chemical and then moved 20 years ago to UOP LLC, which is a Honeywell company. I started to do some user experiments at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory while I was at Dow, and later at other Department of Energy light sources. As soon as I saw the power of what a synchrotron could do in terms of providing insight into the structure of my catalysts, there was no going back. Once you start you’re hooked for life. It’s been quite a ride.

After 30 years working in industry, what made you decide to come to SLAC?

When I heard about an opening at SLAC I thought, "Hmm, why not?" I have done research at SSRL as a user for 20 years and served on their Scientific Advisory Committee, and at meetings I heard the desire to move into catalysis as a new growth strategy here.

SSRL is just a wonderful facility – the people here are amazing – and there’s a huge opportunity to make SSRL the go-to synchrotron for doing catalyst characterization, which is the process of determining a catalyst’s structure and properties.

SLAC and Stanford also jointly operate the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis. It’s been a phenomenally successful theory-driven enterprise, and they are building up their experimental component.

You're a specialist in in situ characterization. What does that mean?

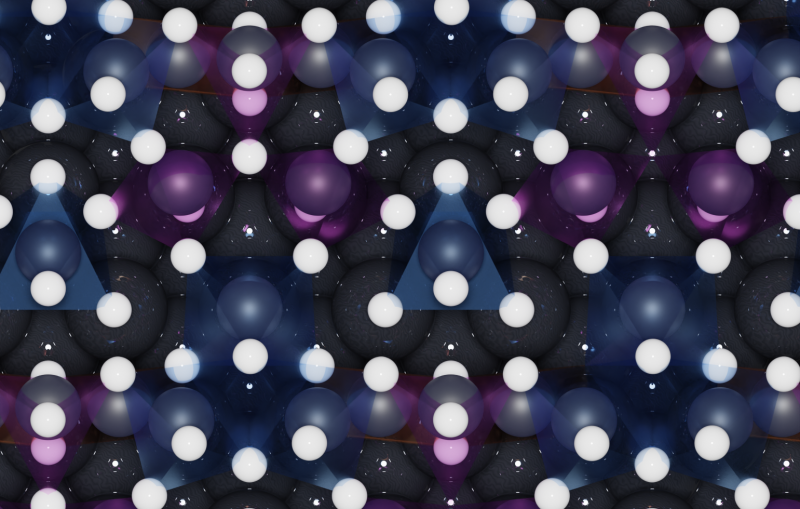

You have a catalyst in a reactor, with reactants feeding in and products going out. You can study that catalyst by stopping the reaction, taking the catalyst out and looking at it with an X-ray beam and determining its structure, but in that case you’re looking at the static state of that catalyst. It’s like watching a game of soccer and all you see is the ball out in the field and then the ball in back of the goal.

I want to watch the exquisite intricacy of how the ball is passed around and how the goal is scored. I want to see the state of the catalyst – electronic, geometric, structural – while it’s actually operating.

One of the things SSRL is great at is designing gizmos that allow you to watch the catalyst in action. But in situ can mean a lot more than just studying the actual reaction. I think the understudied aspect is that you’ve got to make that catalyst, and if I can understand some of the aspects that go into the synthesis, now I can look at that process in situ, too.

With this information you can make the catalyst more selective or make it operate at lower temperature, so is more active. You can understand the whole life of a catalyst, from birth (synthesis) to life (reaction) to death (deactivation); a lot of times you can learn a lot about how a catalyst works by understanding how it deactivates and becomes less active.

What will your own research here involve?

This is evolving. While I do intend to have my own research program here, I see myself more as a facilitator, for want of a better word. I’m putting more effort into helping groups that in my view do world-class research, and being that marriage broker to bring them in here to do work. The lab also wants to increase its visibility with industrial researchers and come up with new means to get them to come to SSRL to do research here.

So it’s more a question of developing capabilities, pushing the frontiers of techniques – that’s where I’ve been focusing these last few months. The rest of it, in my mind, will flow from that.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.