Researchers Discover New Type of ‘Pili’ Used by Bacteria to Cling to Hosts

New insights into how bacteria interact with host cells could help fight off harmful microbes.

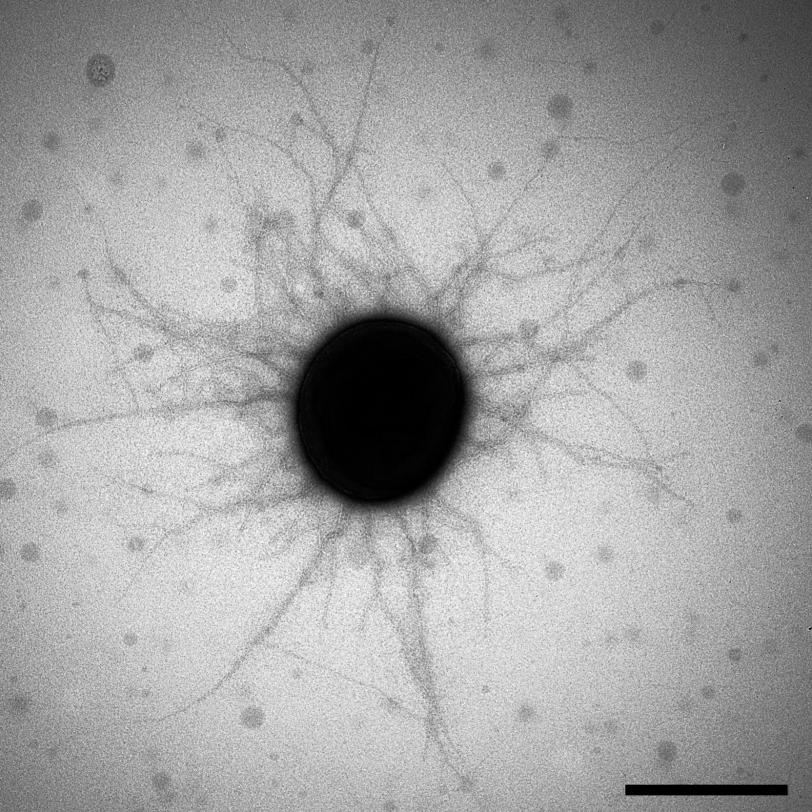

Many bacteria interact with their environment through hair-like structures known as pili, which attach to and help mediate infection of host organisms, among other things. Now a U.S.-Japanese research team, including scientists from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, has discovered that certain bacteria prevalent in the human gut and mouth assemble their pili in a previously unknown way – information that could potentially open up new ways of fighting infection.

The bacteria belong to the Bacteroidia class, whose relationship with humans is best described as a mutual “give and take:” We depend on them for food processing, and they depend on us as a food source. Disturbances of this delicate balance can have severe consequences, ranging from gum disease to inflammatory bowel disease to cancer.

“Pili can also be key virulence factors in these bacteria,” says Ian Wilson, a faculty member at The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla and the principal investigator of the Joint Center for Structural Genomics (JCSG). “If we can design small molecules that bind to pili and disrupt bacterial function, we could potentially develop therapeutics that neutralize their harmful effects.”

The new study, published April 7 in Cell, provides clues on how pili form in the Bacteroidia class, which is an important step toward designing medical interventions.

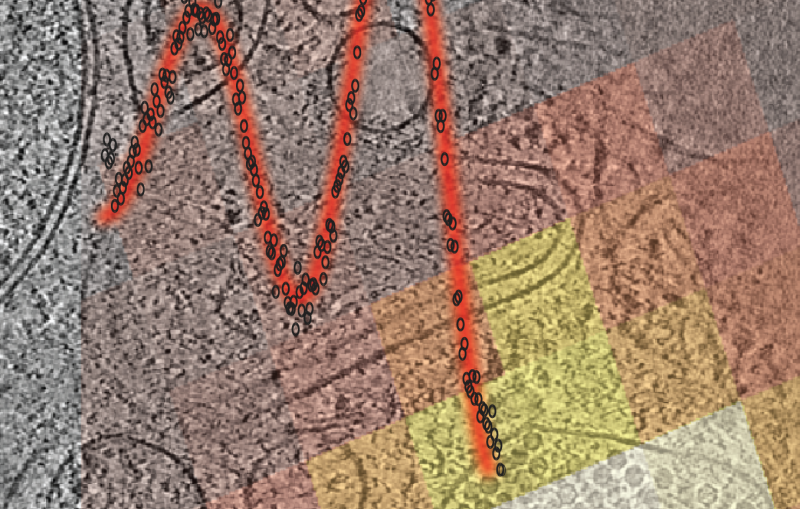

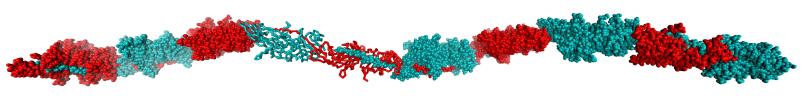

Scientists already knew that pili are made of individual protein building blocks, or pilins, stacked on top of one another. The pili grow by adding more and more pilins to the elongating structure until their growth is terminated by anchoring them to the microbe’s surface.

However, while the molecular details of pili formation have been studied extensively in a variety of microorganisms, they were not known for Bacteroidia.

When the JCSG sifted through data from the human microbiome project, which contains genetic information from bacteria that inhabit the human body, they discovered that the genetic instructions for making Bacteroidia pilins were quite different than those for other bacterial pilins. Did this mean the resulting pili were also different?

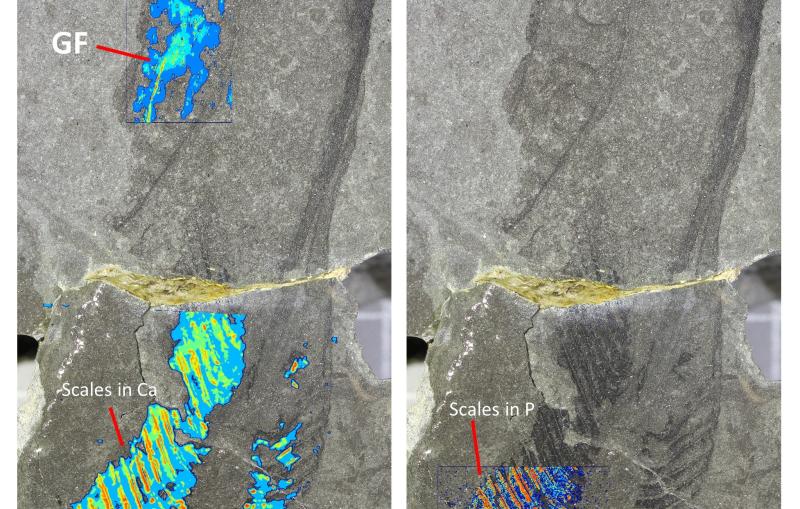

To find out, Wilson and his fellow researchers used powerful X-rays to look at the atomic structures of 20 different Bacteroidia pilins, in experiments largely carried out at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a DOE Office of Science User Facility. These structures, along with biochemical studies by Koji Nakayama’s lab in Nagasaki, Japan, confirmed that the Bacteroidia pilins do indeed form a new type of pili.

“The most striking finding was that Bacteroidia pilins have distinct features not observed in other pilins,” says the study’s lead author, Qingping Xu, a former SSRL and JCSG staff scientist. “In Bacteroidia, pili formation requires additional steps that involve the engineering of each pilin in the protein chain, for instance by clipping parts of the protein off to allow elongation and assembly to occur.”

The study, which suggests that the newly discovered mechanism of pili assembly is widespread in gut bacteria, could tell researchers more about the way microbes interact with their hosts in the gut. In the long run, these data could also inform the design of drugs that target pili to prevent disease.

The following institutions were involved in the research: JCSG; SSRL/SLAC; Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Japan; The Scripps Research Institute; Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation; University of California, San Diego; Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute; and Queen Mary University of London, UK. Research funding for the SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program was provided by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Citation

Q. Xu, M. Shoji, et al., Cell, 07 April 2016 (10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.016).

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.