SLAC and Stanford's James D. Bjorken Shares 2015 Wolf Prize in Physics

The $100,000 Prize Recognizes Theoretical Predictions of the Strong Force and the Structure of the Proton

SLAC theoretical physicist and Stanford Professor Emeritus James D. “BJ” Bjorken has been awarded the 2015 Wolf Prize in Physics for his key role in elucidating the nature of the strong force and predicting what would happen if electrons were violently slammed into protons in the atomic nucleus.

His predictions were confirmed in stunning fashion in the late 1960s by experiments at the newly opened 2-mile-long linear accelerator at what is now the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. They provided strong evidence that the proton consists of quarks, and earned a Nobel Prize for the three scientists who carried them out.

“There was an experimental side and a theory side, and both of them were very brilliant. We’re delighted that the theory side is being recognized with this Wolf Prize,” said SLAC theorist Michael Peskin.

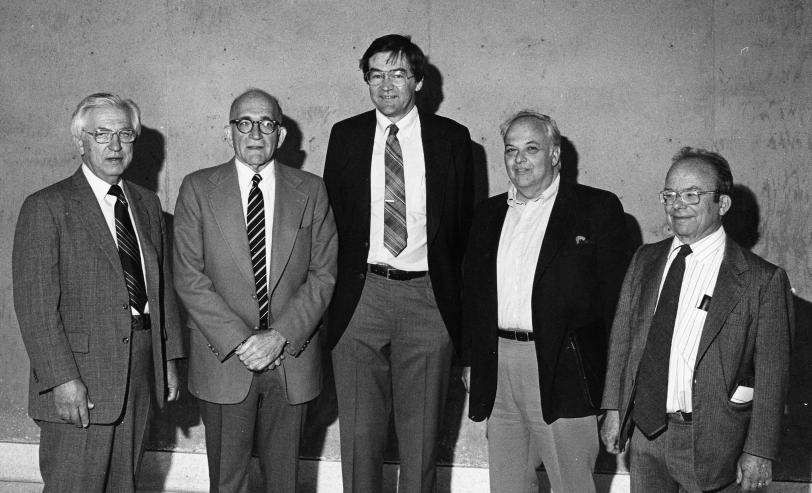

SLAC’s Richard Taylor, who shared the 1990 Nobel Prize in Physics with Henry Kendall and Jerome Friedman of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for performing those crucial experiments, said of Bjorken, “He’s a very, very good theorist and he’s been at the front edge all of his career.”

Fundamental Interactions

In awarding the $100,000 prize, which is shared with Harvard’s Robert Kirshner, the Wolf Foundation noted that the “scaling laws” Bjorken developed to describe how electrons would scatter off particles within the proton led to the discovery of another theory, known as quantum chromodynamics or QCD.

"The prevailing view today is that all fundamental interactions in Nature, with possible exception of gravity, are described by theories whose mathematical structure is analogous to QCD,” the foundation wrote in its citation. “Thus in retrospective, Bjorken's scaling not only led to the discovery of quarks, but also pointed the direction toward the mathematical framework governing all fundamental interactions.”

Bjorken, who retired from SLAC in 1998, said, “This prize is part of SLAC’s story. It’s greater than me, and even more than Friedman, Kendall and Taylor. It’s a great accomplishment of the first generation of this lab – of Pief Panofsky, who had the vision of setting up SLAC, and of the people who built and operated the accelerator. The entire lab should be sharing this happy moment.”

Bjorken divides his time between his home near Stanford and Teton Valley, Idaho, where he has a second home in a small town with a growing population of retired particle physicists. He still comes into SLAC for weeks at a time and travels around the country for deep conversations with fellow physicists on topics like general relativity, dark matter and dark energy. “I’ve found the most efficient way to test ideas and get hard criticism is one-on-one conversation with people who know more than I do,” he said.

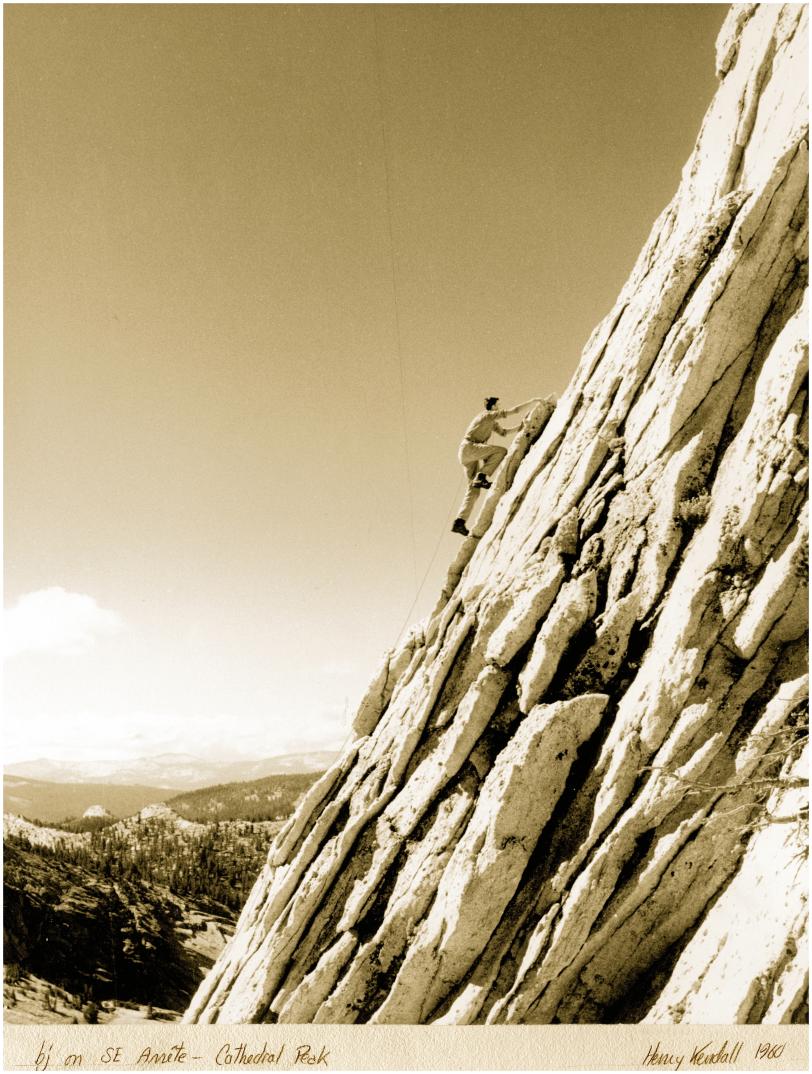

Scaling Physics and Mountains

Bjorken studied physics at MIT and came to Stanford as a graduate student in 1956 along with his adviser, Sidney Drell, future SLAC Director Burton Richter and a number of other MIT physicists who would become instrumental in the founding of SLAC. They were lured by experiments at an early linear accelerator on the main campus, where electrons were being scattered off atoms in a target to reveal the nature of the proton and neutron – work that would win Stanford’s Robert Hofstadter a Nobel Prize.

In 1966, these so-called “elastic scattering” experiments moved to SLAC’s newly opened 2-mile-long linear accelerator. Bjorken, who had been working on theory, began lobbying the experimental team to test another process, dubbed deep inelastic scattering.

“The idea was to have electrons knock protons into smithereens as violently as you could arrange it,” he recalled. “This was not trendy at the time.”

Bjorken talked up the idea, taking advantage of long drives with Kendall and other members of the experimental team while on mountain climbing trips with the Stanford Alpine Club. He says there’s a good chance the inelastic scattering experiments would have taken place even without his lobbying, but “I catalyzed things and brought the idea into the foreground, and I’m glad I did.”

Implementing the idea at SLAC required a novel mathematical language. Bjorken contributed to the development of that language, taking it in an adventurous new direction. Further simplifications and improvements were made by Caltech physicist Richard Feynman and Bjorken’s students, John Kogut and Davison Soper.

Going Against the Grain

Bjorken earned his PhD at Stanford in 1959, became part of the Stanford and SLAC faculties and in 1979 left for Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, where he was associate director for physics. He returned to SLAC in 1989.

As a theorist he continued to innovate. Among other things, he invented ideas related to the existence of the charm quark and the circulation of protons in a storage ring and popularized the unitarity triangle – a way of graphically depicting measurements made by the BaBar detector at SLAC. He and Drell also co-wrote two widely used graduate-level textbooks – Relativistic Quantum Mechanics and Relativistic Quantum Fields.

Among other honors, he has been awarded the American Physical Society’s Dannie Heinemann Prize in Mathematical Physics, the Department of Energy’s Ernest Orlando Lawrence Medal and the Dirac Medal from the International Center for Theoretical Physics.

“He has a really different perspective on things,” said SLAC theorist Lance Dixon, ”and sometimes it takes a while for people to see things the same way. His intuition is all his own – he developed it on his own, rather than reading it somewhere else – and it’s always deep.”

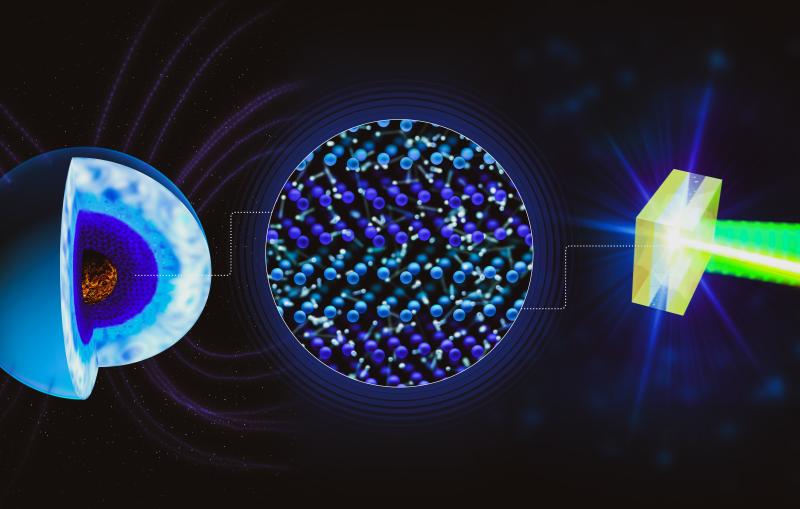

Bjorken is also known as one of the few theoretical physicists who have carried out experiments – at SLAC in the early 1980s and at Fermilab’s Tevatron collider in the 1990s. In 2009 he contributed to an influential paper written by three younger theorists – Rouven Essig of SLAC and Philip Schuster and Natalia Toro of Stanford – suggesting new approaches for experiments that would search for the carrier of a new fundamental force, the “heavy” or “dark” photon.

Essig, Schuster and Toro, who have since moved on to other institutions, are now co-spokespeople for the APEX Experiment and are also involved in the SLAC-led Heavy Photon Search, both of which are searching for evidence of such a dark photon at Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility.

“I fervently hope they find it,” Bjorken said. “It would go against the grain of most conventional thought.”

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.