Research Pinpoints Role of 'Helper' Atoms in Oxygen Release

Experiments at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory solve a long-standing mystery in the role calcium atoms serve in a chemical reaction that releases oxygen into the air we breathe.

Experiments at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory solve a long-standing mystery in the role calcium atoms serve in a chemical reaction that releases oxygen into the air we breathe. The results offer new clues about atomic-scale processes that drive the life-sustaining cycle of photosynthesis and could help forge a foundation for producing cleaner energy sources by synthesizing nature's handiwork.

The research is detailed in a paper published Sept. 14 in Nature Chemistry. X-ray experiments at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, played a key role in the study, led by Wonwoo Nam at Ewha Womans University in Korea in a joint collaboration with Riti Sarangi, an SSRL staff scientist.

"For the first time, we show how calcium can actually tune this oxygen-releasing reaction in subtle but precise ways," said Sarangi, who carried out the X-ray work and supporting computer simulations and calculations. "The study helps us resolve the question, 'Why does nature choose calcium?'"

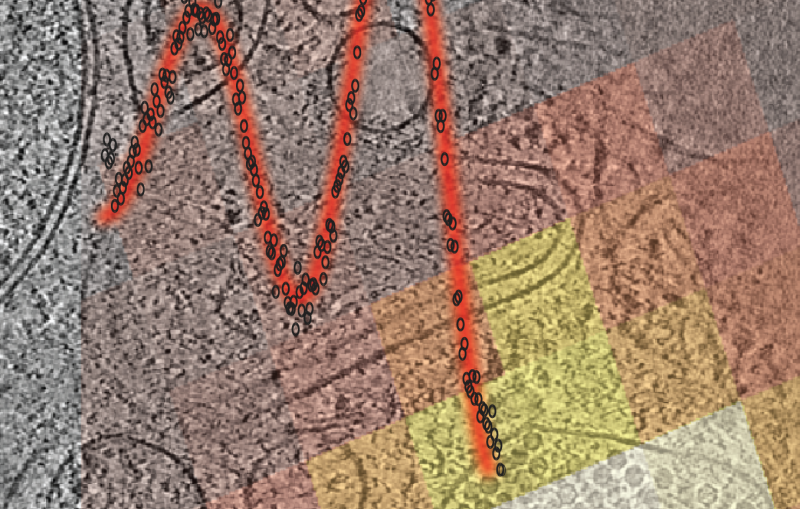

Photosynthesis is one of many important biological processes that rely on proteins with metal-containing centers, such as iron or manganese. The chemistry carried out in such centers is integral to their function. Scientists have known that the presence of calcium is necessary for the oxygen-releasing stages of photosynthesis, but they didn't know how or why.

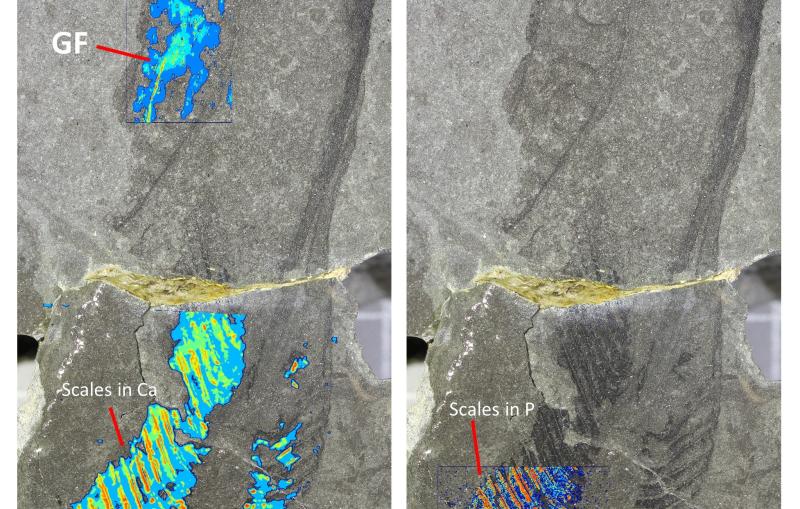

The SSRL experiment used a technique known as X-ray absorption spectroscopy to explore the chemical and structural details of sample systems that mimic of the oxygen-releasing steps in photosynthesis. The basic oxygen-releasing system contained calcium and was centered around an iron atom.

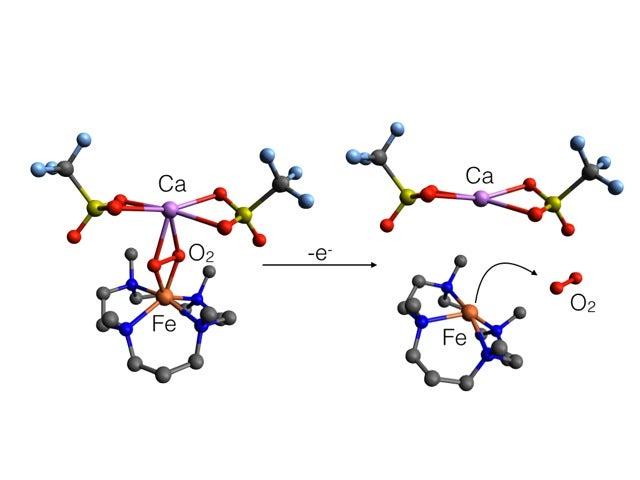

Researchers found that charged atoms, or ions, of calcium and another element, strontium, bind to the oxygen atoms in a way that precisely tunes the chemical reaction at the iron center. This, in turn, facilitates the bond formation between two oxygen atoms. The study also revealed that calcium and strontium do not obstruct the release of these bound oxygen atoms into the air as an oxygen molecule -- the final step in this reaction.

"We saw that unless you use calcium or strontium, this sample system will not release oxygen," Sarangi said. "Calcium and strontium bind at just the right strength to facilitate the oxygen release. Anything that binds too strongly would impede that step."

While the sample system studied is not biological, the chemistry at work is considered a very good analogue for the oxygen-releasing steps carried out in photosynthesis, she said, and could assist in constructing artificial systems that replicate these steps. The next step will be to study more complex samples that perform more closely to the actual chemistry in photosynthesis.

Other participants in this research were from Osaka University in Japan and the Japan Science Technology Agency. The research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan. SSRL's Structural Molecular Biology program is supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Office of Biological and Environmental Research of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Citation: S. Bang, et al., Nature Chemistry, 14 September 2014 (10.1038/nchem.2055).

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.