Fossil Leaves Preserve Living Chemistry

X-ray studies conducted at SLAC and in the United Kingdom have resurrected the detailed chemistry of 50-million-year-old leaves from fossils found in the western United States and found striking similarities to their modern descendants.

X-ray studies conducted at SLAC and in the United Kingdom have resurrected the detailed chemistry of 50-million-year-old leaves from fossils found in the western United States and found striking similarities to their modern descendants.

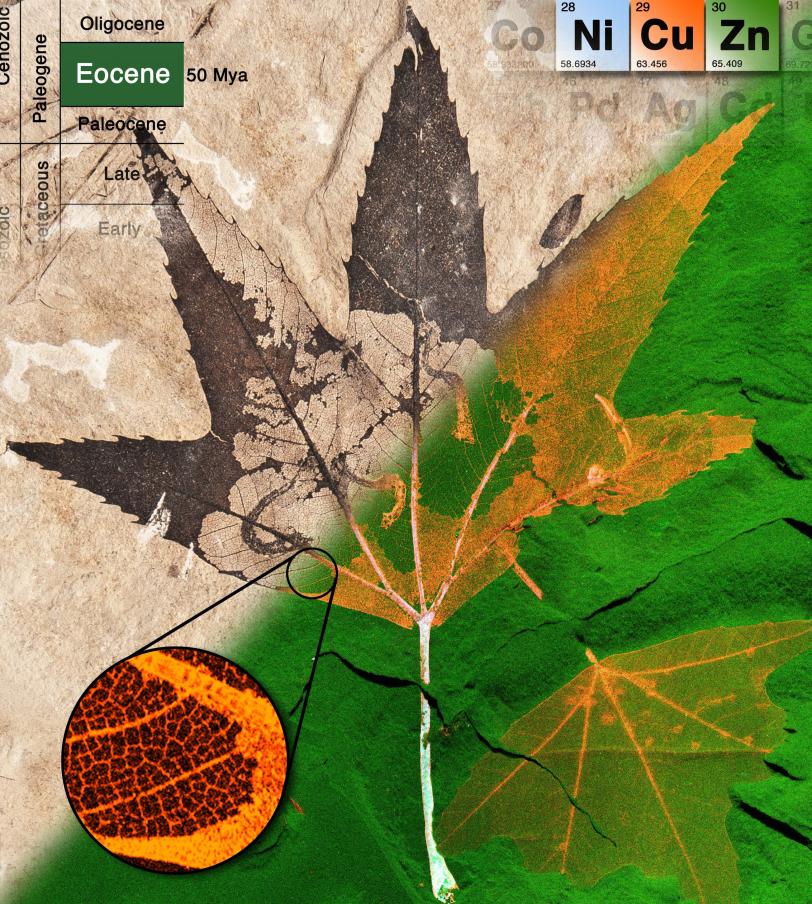

Using the same nondestructive X-ray fossil-scanning techniques that revealed color patterns in the plumage of an early "dinobird," researchers mapped for the first time the traces of various metals that remain in the fossil leaves and compared those to the location and concentration of the same metals in modern leaves.

Based on detailed images and related research, the researchers concluded that the metals present in the fossil leaves are a product of their living chemistry.

The distribution of copper, zinc and nickel in the fossil leaves, recovered from a region of ancient lakebeds in Colorado, Wyoming and Utah, is almost identical to that in modern leaves. Each element is concentrated in distinct leaf structures, such as the veins and edges. Also, the way these trace elements and sulfur were attached to other elements was very similar to that seen in modern leaves and plant matter in soils.

"This opens up the possibility to study part of the biochemistry of ancient plants, so in the future it may enable us to observe the changes, if any, in the use of metals by the plant kingdom through time," said Nick Edwards, a researcher at The University of Manchester and lead author of the study, published in the March 26 edition of the Royal Society of Chemistry Journal Metallomics.

The research took place at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and at the Diamond Light Source in the UK.

"These fossil explorations may lead us to a greater understanding of how the complicated chemistry of life has developed," said Uwe Bergmann, interim director of SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser. Bergmann participated in the study and also conducts research at SSRL and LCLS on the oxygen-producing complex of photosynthesis as a potential path to clean energy.

Studies of well-preserved plant fossils could provide clues to whether plant chemistry has changed over millions of years, leading to a better understanding of our planet's ancient environment, the researchers said. The intricate biochemistry of fossilized plants had not previously been studied in such detail.

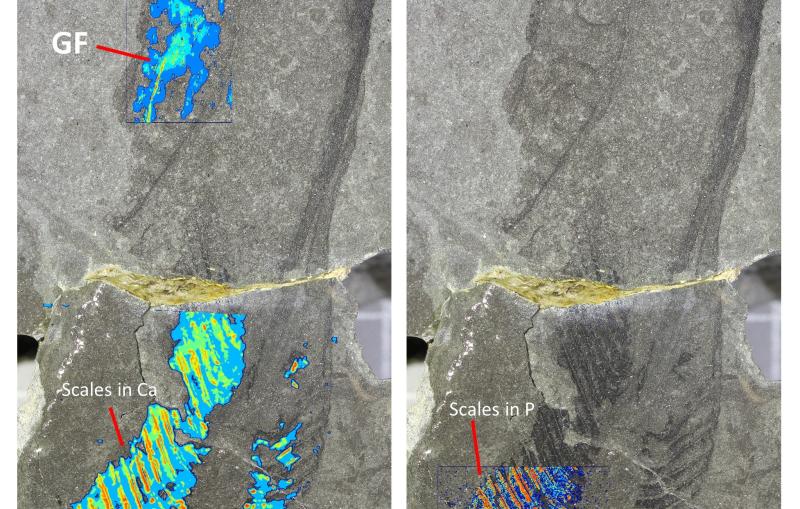

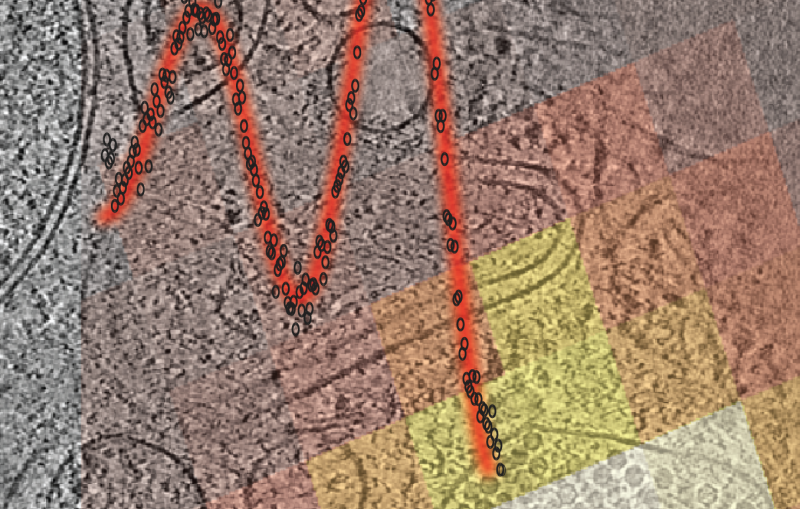

"In one beautiful specimen, the leaf has been partially eaten by caterpillars and their feeding tubes are preserved on the leaf," said Roy Wogelius, a professor at The University of Manchester who participated in the fossil research. "The chemistry of these fossil tubes remarkably still matches that of the leaf on which the caterpillars fed."

He added, “This type of chemical mapping and the ability to determine the atomic arrangement of biologically important elements can only be accomplished at a synchrotron."

As with animal fossils, the natural occurrence of copper in the plant fossils may have helped to preserve their fine details, said Phil Manning, a paleontologist at The University of Manchester who also took part in the study.

"This property of copper is utilized today in the same wood preservatives that you paint on your garden fence," he said.

Citation: N.P. Edwards, P.L. Manning, et al., Metallomics, 26 March 2014 (10.1039/C3MT00242J)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource is a third-generation light source producing extremely bright X-rays for basic and applied science. A DOE national user facility, SSRL attracts and supports scientists from around the world who use its state-of-the-art capabilities to make discoveries that benefit society. For more information visit http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.