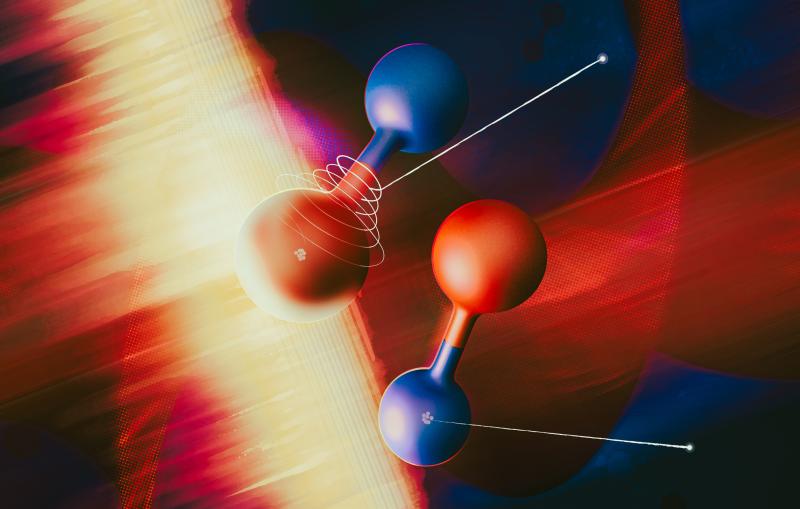

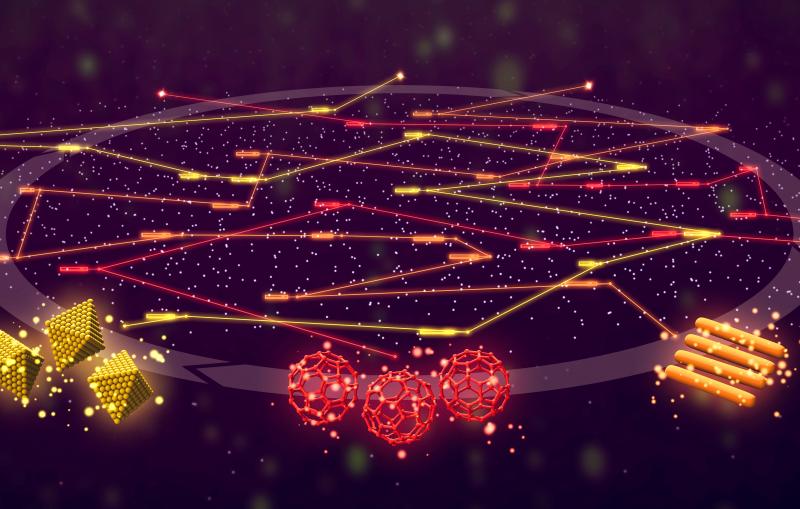

The Linac Coherent Light Source - II, or LCLS-II, once fully operational, will be able to generate

one of the most powerful X-ray beams in the world.

Generating this much energy will also mean lots of heat.

This heat poses a challenge since a portion of LCLS-II will need to have superconducting capabilities.

To keep the accelerator cold enough to be a superconductor, the Cryogenics team here

at SLAC has assembled a cryoplant capable of cooling helium to 2 Kelvins, or roughly

-271 degrees celsius.

This helium, once in its liquid state, will be pumped into the accelerator modules, keeping

LCLS-II cold enough to generate its powerful X-rays, but why chose helium as a coolant

in the first place?

The helium is the only fluid that would be a liquid or gas at this type of temperature.

There’s no other fluid that would help us to reach 2 or 4 kelvins.

Selecting helium as the coolant is the easy part.

The real trouble is cooling this helium from room temperature to 2 kelvins.

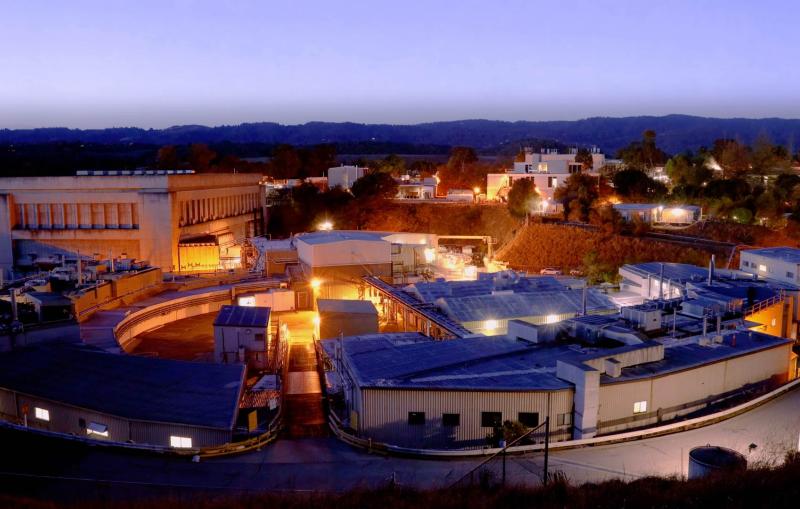

To begin the process, roughly four metric tons of helium are transported to SLAC and

deposited into several outdoor storage tanks.

After delivery, the helium is purified, pressurized and cooled using a highly complex process

that involves cooling water, liquid nitrogen, turboexpanders and decompression.

After these steps, the helium is cooled to roughly 4.5 kelvins, or about -269 degrees celsius

The helium is now in its liquid state, and it travels through pipes into LCLS-II’s

cryomodules, but it’s not quite cold enough yet.

To reach 2 kelvins, there is one final step.

So the helium that has been produced by the cryoplant goes down to 4.5 kelvins,

it’s then transferred to the LINAC, where it’s going to expand.

We expand down to a pressure of 30 millibars and when we reach 30 millibars,

the helium temperature drops to 2 kelvins.

The 30 millibars have been achieved using a train of 5 cold compressors.

After the helium goes through this process, it is recycled back into the system to be

used again.

This way, there is little to no wasted helium, allowing the cryoplant to continue running

for extended durations of time.

Now that the plant itself is assembled and functional, the process of cooling helium

seems deceptively simple.

The cryoplant here is fairly automated.

There’s a large number of operations that are completely automated.

It includes most of the start-up, most of the operation phase and also the shutdown.

This is being done to limit the amount of resources required to operate the plant that

is now running 365 days/year and 24/7.

Even with a robust team of engineers and operators backing this system, the road ahead will not

be without its challenges.

The challenge is so: as of today, the LINAC is operating at 2 kelvins, and we have very

limited heat load generated by the LINAC.

As we move forward, and as we are going to increase the load provided by the cavities

and by the LINAC, we will need to provide more cooling power to the system.

And the challenge for us will be to make sure that the capacity of the cryoplant is matching

the requirement from the LINAC, that is the total heat load that is going to be generated

by the cavities and the cryo-modules when they are turned on to their full gradient.

The LCLS-II accelerator is expected to produce its first X-ray beams in early 2023.

For those first experiments, only one of two cryoplants will be used.

The second plant, housed in the same building, is in the process of being assembled and will

be used for upgrading LCLS-II’s capabilities when the time comes.