michael peskin: I'd like to welcome you all to the latest installment of the slac public lectures socially distanced please excuse us but it's still the situation.

michael peskin: Most likely we will have one more of these socially distance lectures at the end of July and then we'll see what the situation is in the fall, it would be great to see you folks all in person in the big panofsky auditorium but we don't have yet the permission to do that.

michael peskin: Today we're going to hear a very interesting lecture by Arianna Gleason a staff member at slac i'll talk about that in just a moment, but first i'd like to call your attention to two features which, if you put your cursor at the very bottom of your zoom window you'll see.

michael peskin: first of them is the Q&A so if you have a question during the talk, please type it into the Q&A.

michael peskin: And at the end of the talk will have 20 minutes or so with Arianna and two of her colleagues listed here as panelists to answer these questions.

michael peskin: And yeah don't be afraid to stray outside of the narrow bounds of this lecture these people have their minds open so let's find out what they have to say about your question.

michael peskin: The second thing is, you will see a CC live transcript So if you push that button, you will get closed captioning.

michael peskin: um i've had some experience with zoom closed captioning it's it has gaffes so just don't laugh too loud, but we hope that for those people who need it.

michael peskin: It it will be a useful feature, so please avail yourself of those two buttons at the bottom of your zoom screen and we look forward to your questions at the end of the talk.

michael peskin: Okay well now let's get started Arianna Gleason is a staff member here at slac at the linac coherent light source our free electron X Ray laser and a member of the.

michael peskin: hdd high energy density group here, these are the people who who basically irradiated things and study matter at extremely high temperatures and pressures.

michael peskin: And why that is relevant to the origin of life is more or less the subject of this talk Arianna got her PhD from Berkeley in 2010 actually an earth and planetary science then she went to.

michael peskin: postdoc at Stanford to Los Alamos national laboratory and there she worked on shock waves and materials and then she joined the slack effort here on high energy density.

michael peskin: she's an expert on visualizing the behavior of material under really extreme conditions and you'll see a little of that in this talk.

michael peskin: Actually an interesting part of her career occurred earlier as an undergraduate she worked as an undergraduate astronomer with the spacewalk project at the University of Arizona.

michael peskin: and actually discovered some comets and asteroids that are now named after her so her name is in the heavens, and we will see more about that in the course of this lecture.

michael peskin: So Arianna please take it over look you'll tell us about the shocking origin of life with meteor impacts and extreme conditions of chemistry, so thank you very much.

arianna gleason: Thank you, Michael and welcome to my friends and colleagues and visitors who are attending this lecture i'm very privileged to work here at the slac national accelerator laboratory.

arianna gleason: I also have a position in the geosciences department at Stanford as an adjunct faculty.

arianna gleason: And i'm very lucky to work with such an extraordinary group of scientists and colleagues, two of which I am fortunate enough to have here, so please stay tuned.

arianna gleason: For exciting discussions with Dr. Richard Walroth and Professor Richard Sandberg at the conclusion of this of this talk.

arianna gleason: And so diving in to one of the most exciting questions and exciting challenges of our time thinking about the origin of life and the different ways in which scientists are pursuing.

arianna gleason: This question, it can be thought of very broadly in a philosophical sense in a religious sense, but also in a scientific and origin sense and aspects of that we will discuss today.

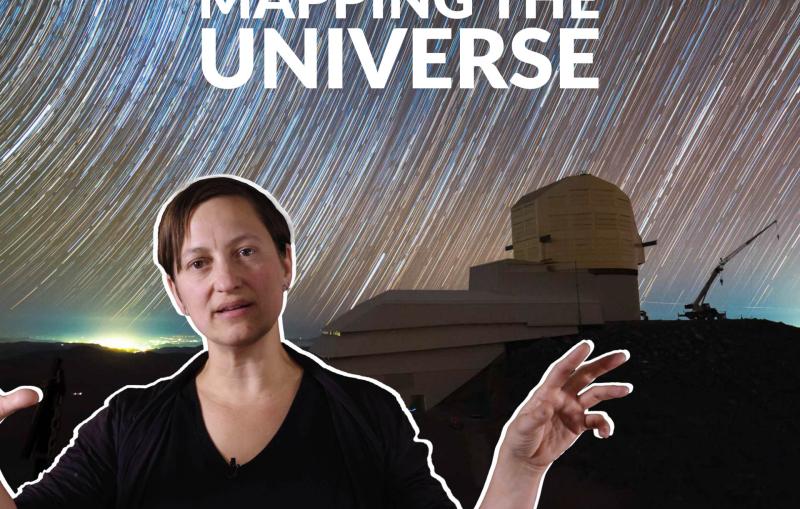

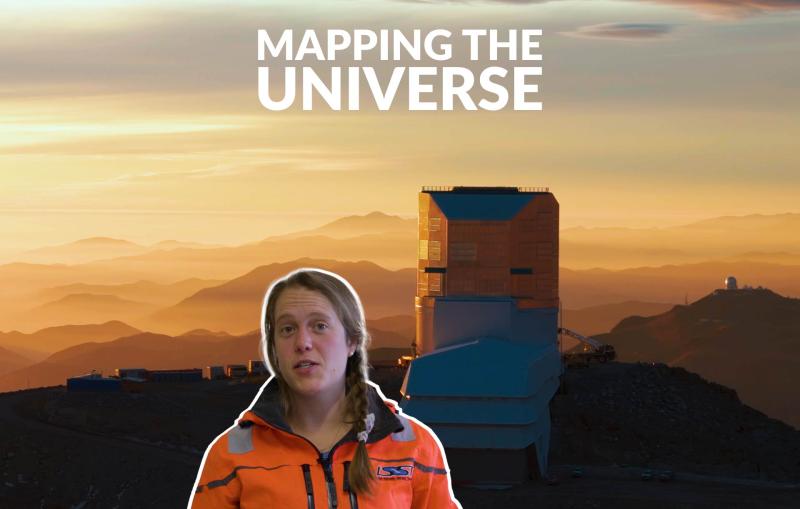

arianna gleason: But first i'm going to share with you a little of my own origin story as Michael mentioned, I have always been excited.

arianna gleason: intrigued by the heavens, and in in various opportunities, even in my younger early days, of which I have an embarrassing photo in the upper left attended some astronomy summer camps that extended into really fantastic.

arianna gleason: Education and experiences at the University of Arizona, where I did my undergraduate work and was fortunate enough to work with a team.

arianna gleason: called space watch and there we studied and catalogued near earth asteroids in working at the kitt peak observatory in Arizona shown here above my head here's a photograph I took from the top of our.

arianna gleason: 1.8 meter telescope that was used to survey the skies, I was lucky enough to be bestowed with a named main bell asteroid so called asteroid gleason.

arianna gleason: And in during my time those with those serving I found a Comet so there's a fuzzy little image here in in the Center of your screen and it turns out to be a long period Comet.

arianna gleason: here's a much younger picture of myself at the 36 inch telescope so many years ago, and this interest in the location and origin of these bodies actually translated into my pursuits later in my graduate school career and postdoctoral career.

arianna gleason: In the early 2010 I joined the extreme environments laboratory here at on campus at Stanford here's a photograph of that.

arianna gleason: The the team there we study rocks and minerals under extreme conditions high pressure high temperature that mimic the conditions of the inner.

arianna gleason: The inner planets the inner core and other terrestrial bodies, and that is.

arianna gleason: an exciting way to investigate how matter transforms at these extraordinary conditions.

arianna gleason: And later on i've been lucky enough to join the hdd high energy density group here at slac where i've continued this work and coupled this interest in.

arianna gleason: location and identification of these comets and asteroids into finding out what are they made of and how could this be connected to the origin of life.

arianna gleason: So here's an outline for this evening's lecture first we'll talk about the different hypotheses around the origin of life, you might be familiar with, with some of these very exciting and.

arianna gleason: Ongoing active area of research next we'll talk about what are we doing in our laboratories here at slac

arianna gleason: To investigate one of these hypotheses so called the impact synthesis hypothesis, in order to do that, we have to be able to visualize.

arianna gleason: dynamics and changes in the meteoritic material in the chemistry and the chemicals involved at very fast timescales, so we need a high rate ultrafast camera.

arianna gleason: And that's something that we can do here at slac and then in the end, I think the punch line of the entire story here is that in fact life at least primitive life may be more common than we previously thought.

arianna gleason: So to sort of step back and consider the broad picture.

arianna gleason: exobiology in the search for life is anybody out there is an exciting and grand challenge, especially of our day.

arianna gleason: And we need to consider what is in that recipe, what is required, well, we need the materials, in fact, the planets that provide habitability for life.

arianna gleason: We need the appropriate chemistry to kick us off what's what's in that recipe book, what are the building blocks.

arianna gleason: In a chemical sense that enable life water liquid water is a fact, one of the main ingredients and understanding, where liquid water is present in our solar system and in other locations, is also very important.

arianna gleason: And then finally energy in order to kick start actually seed, what is the building blocks of life to go from a biotic to biotic requires energy and the different hypotheses toward investigating which one is the one hypothesis, and that.

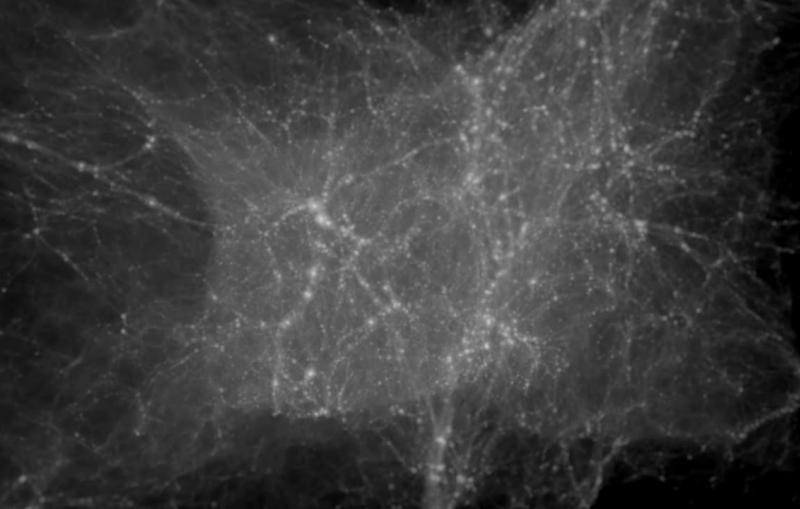

arianna gleason: Energy deposition into a system is part of what we'll discuss here today and I think the punch line is primitive life or life is actually far more common I think that's a very exciting notion, so if we zoom all the way out and think about.

arianna gleason: Where we are in the universe, in fact, the Earth is 14 billion years old, so the the the laws of chemistry and physics, have had an awfully long time to try to get this recipe just right.

arianna gleason: It in the universe, there are hundreds of billions of galaxies and that's just mind blowing but more than that.

arianna gleason: Each galaxy has about 100 billion stars okay so that's also an extraordinary number and each of those stars could be considered as the sun.

arianna gleason: Now most stars have planets and over the recent years so many exoplanets have been discovered in fact.

arianna gleason: There are searches, you could do to look up how many exoplanets have been discovered and confirmed and just recently I looked up this number over 4000 exoplanets.

arianna gleason: That are near the habitable zone have been discovered and confirmed of those 60 or more, this is likely just a limit of what we understand.

arianna gleason: 60 or more are just right in that goldilocks regime that habitable zone that has the appropriate chemistry and energy required.

arianna gleason: And the laws of physics and chemistry are the same everywhere, so this really positions this question well to say Oh, my goodness.

arianna gleason: Life primitive life is far more common than we previously thought so let's talk about what are the requirements what's in this recipe book for life.

arianna gleason: And how does something go from very simple to very complex so here on this graph I show in the upper right hand corner.

arianna gleason: The simple side so we'll start there and let's walk through one by one, all the way to complex and you may be familiar with terms like amino acids or RNA.

arianna gleason: or DNA DNA is the the holder of the genetic code, it is the indicator as, as it were.

arianna gleason: And so, how do we build up this complexity well there are very common a set of common elements that are required to to begin this process that is carbon hydrogen.

arianna gleason: oxygen and nitrogen and we are fortunate, it is fortunate that this is in abundance in our solar system, each of these elements is in abundance in our solar system.

arianna gleason: And across the universe, and these different elements can come together to form very simple molecules which I show here.

arianna gleason: CH4 methane which you're probably familiar with some of us produce it from time to time NH3 ammonia, this is think of it as window glass cleaner.

arianna gleason: Water liquid water is of course necessary and paramount carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide.

arianna gleason: it's what we produce when we exhale these very simple molecules can come together in more complex ways and so What do I mean by complex, I mean the ability to build up.

arianna gleason: These very fundamental building blocks amino acids that are found in RNA and so let's look at this next piece, so the the simple molecules that we've shown here can infect break apart and reform in certain ways to produce the four nucleobases of RNA.

arianna gleason: Then we need to think about an additional level of complexity so we've gone from simple molecules that we're familiar with to something more complex.

arianna gleason: But now it comes to the structure of this RNA that then leads to to DNA, the structure is a helical structure right and it's a chain.

arianna gleason: So we also have to consider how these molecules are building up complexity chemically but structurally in order to satisfy these requirements and it turns out, the structure is key and we'll see that.

arianna gleason: Read we'll revisit that topic of structure and how different.

arianna gleason: surrounding material, maybe host rock and mineral material provides that template that image required for building up these chains of more complex nucleobases in the RNA so template you may be familiar with something called bio mineralization where biological.

arianna gleason: materials are found commonly in on certain minerals and rocks, and this is a very fascinating area of research, wherein on the surface of a mineral or a rock there's a certain surface.

arianna gleason: affinity for for different bonding different chemistry and what can happen is there can be an encouragement and enticement.

arianna gleason: of perhaps some of these very simple molecules to build up its complexity, so called synthesis polymerization right and self assemble in that in that particular structure.

arianna gleason: And that might actually be one of the key ingredients that need to be considered when looking forward to the the possibilities, the origin of life.

arianna gleason: So there are several hypotheses that have been put forward and commonly discussed in the scientific community around how to build up the complexity required.

arianna gleason: The first one, you might be familiar with so called the Miller-Urey experiments which took place in the early 1950s, it is essentially the.

arianna gleason: combination of simple molecules and a bolt of lightning so it's lightning striking a pond, as it were, so this experiment, there was a requirement of some water vapor liquid water.

arianna gleason: And then water vapor in the presence of these very simple molecules we mentioned earlier, and then there is a bolt of lightning or a strike from an electric spark.

arianna gleason: That enables these materials to break apart the simple molecules disassociate and reassemble in a more complicated fashion.

arianna gleason: And this experiment was what was very exciting and in fact the organic molecules the this the materials that were formed did indeed craft the amino acids that are.

arianna gleason: required the the the ones that are exactly required for life Okay, in fact, there are over 70 different kinds of amino acids, of which only 20.

arianna gleason: Only 20 are in our biology here so that's interesting that there's actually a wider variety of amino acids than actually what life uses in the biological construction.

arianna gleason: Another hypothesis that's put been put forward again, you may be familiar with extremophiles so micro organisms and materials that are actually thriving.

arianna gleason: Not just surviving but thriving in extraordinary extraordinary number and the locations, you may least expect.

arianna gleason: One is so called a black smoker, this is a region in the depths of the ocean, where the crust is being pulled apart and there's an upwelling of hot magnetic material.

arianna gleason: As this magma up wells tremendous heat geothermal heat his input into the system and there's an interaction of of metallic.

arianna gleason: minerals of high Z minerals in concert with the circulating seawater this environment is ripe for spurring on

arianna gleason: These extremeophile micro organisms, you may also be familiar with hot springs where differences in pH very acidic very basic can actually generate these beautiful colors that we may.

arianna gleason: view and, in fact, there is a rich or their rich colonies of extremeophiles that that persist in these unusual places, and then we arrive at today's topic which is an impact, I sent this type of synthesis.

arianna gleason: Here we consider the fundamental materials, the simple molecules as ride along as as.

arianna gleason: Participants that ride along on different kinds of rocks and minerals in space we could talk about collisions then.

arianna gleason: Of these different components collisions or impacts between dust screens between meteorites or even as large as large as asteroids and materials that build up to a planetary scale.

arianna gleason: And it's this input of energy during that impact event that dynamic process during the collision it's very short lived.

arianna gleason: But it has an extraordinary amount of energy could that be the input of energy required to break apart and have the molecules rebuild in a more complex way.

arianna gleason: that's what we're going to explore today and we're going to use as our vehicle in this case, to consider meteorites now meteorites are fascinating area of study.

arianna gleason: And in of themselves in fact there's quite quite quite a bit of diversity in meteoritic material and a meteorite is a rocky remnant.

arianna gleason: of an asteroid or Comet that falls to a planetary surface, in fact, we have meteorites that have come from Mars and that's a that's a wide area of exciting study, here we survey the different types from so called chondritic material, this is very carbon rich.

arianna gleason: meteorites to iron meteorites you may have you may have seen possibly a slice through one of these, and the different minerals actually dissolve separate from one another one another, making this beautiful.

arianna gleason: Inter lacing sort of finger pattern there also minerals, excuse me meteorites so called Pallasite meteorites that have both components of a of a rocky.

arianna gleason: planet meaning both silicate rich and iron in the same material in the same meteorite and then you go all the way to achondritic, meaning absence of.

arianna gleason: Carbon rich components and these meteorites are messengers mixing across the solar system, in a sense, you could think of them as.

arianna gleason: The solar system uber right they're moving material around from point A to Point B they in fact contain meteorites have been examined.

arianna gleason: That contain all 70 amino acids so let's just pause right there and take that in meteorites have fallen to the earth that already contain.

arianna gleason: The building blocks of life Okay, so this is very exciting they contain a wide range of organic material, not just a very simple molecules, but in fact manifesting this build up already of the complexity.

arianna gleason: We are going to then consider what's required what's that recipe for life look like in the context of meteorites so we've got here on this image.

arianna gleason: Information that tells us from the study of different meteorites that actually these meteorites have source their amino acids from different regions in the solar system.

arianna gleason: So there's a wide there's a an incredible opportunity for the prebiotic materials present already.

arianna gleason: there's also through the impact and collision process, there is a mechanism to go from simple to complex through that shock wave.

arianna gleason: And impact process and we're going to walk through exactly what that means in a moment, here in the talk.

arianna gleason: But the last thing that I want to draw your attention to is the mineralogy itself the minerals within these different meteorites may hold the key.

arianna gleason: For how that complexity is built up in just the right way that helical shape that is a part of RNA and the other complexities, enabling the chain to go from.

arianna gleason: Individual amino acids to a more lengthy chain and building up of the complexity that might be enabled in fact by the minerals themselves so understanding how those minerals change.

arianna gleason: During that impact process might give us incredible insight into in fact what kick starts that origin of life.

arianna gleason: So previous work has investigated this very question and in 2014 there was a study done where they began with a very simple molecule it's called formamide.

arianna gleason: Okay, so formamide is actually quite common it's found extensively in interstellar clouds so it's very common in.

arianna gleason: In in the in space and a good source material, it also can form all four nucleobases okay that are required and is a constituent component.

arianna gleason: Of RNA Okay, so all four required nucleobases can form, but how do we get from formamide to the nucleobases? well as a concept was put forth by these colleagues.

arianna gleason: Or the this work in 2014 suggesting that an impact or high collision high energy density process, such as a collision.

arianna gleason: Could could generate the complexity required break apart, this formimide, which is oxygen hydrogen nitrogen break it apart and in that dynamic process reassemble.

arianna gleason: Two more complex materials and this idea is also put forward by a colleague of mine who's joining us as a panelist Dr Richard Walroth, and so I want to be sure, and extend.

arianna gleason: The the notation to him that this is part of our collaborative idea and his his idea as well, so this work in 2014 from from previous investigators, they sent in a high power laser.

arianna gleason: They wanted to blow stuff up right break that formamide apart and then visualize watch what happens in time to see the actual re development of the more complex material.

arianna gleason: But the issue may be that their camera their way of visualizing the the complex build up wasn't quite fast enough and that key aspects of that are actually missing and we don't know we can't see it yet and that's where the tools that slac can come in.

arianna gleason: So what are our tools that we use to investigate these very extreme conditions and the materials at extreme conditions, here I show a view graph.

arianna gleason: That illustrates some aspects of high pressure, you might be familiar with, such as a can of soda so it at ambient condition, where we are here let's say it's slac or you are.

arianna gleason: watching me through this webinar the can of soda has in its carbon dioxide that's been pressurized to lock it in so when you open it.

arianna gleason: you hear the release of that that CO2, you might be familiar with high pressure in the sense of.

arianna gleason: helium that supplies your balloon to lift for a birthday party, you may be aware of increased pressures at the base of the of the ocean that a tremendous column of water pressing down.

arianna gleason: There are other ways to generate extreme pressure thermonuclear thermonuclear testing there's also extraordinary pressure at the Center of the earth, in fact.

arianna gleason: 3 million times our atmospheric pressure okay that's an extraordinary number to consider, but these are the pressures, these are the conditions that are at play.

arianna gleason: During these collisions of course there's much higher pressure, certainly at the Center of larger planets Jupiter and, of course, at the Center of stars.

arianna gleason: And we have a set of tools here at slac and across the globe to mimic those same pressure and temperature conditions and I show these at the bottom from very simple.

arianna gleason: of pressure vessels that can exist in a laboratory to ton presses that bring down additional pressure up to.

arianna gleason: Several hundred times atmospheric to something called a diamond anvil cell and so on and so forth, until we get to lasers and the ability of lasers, to actually generate high pressure in the material, and this is essentially.

arianna gleason: Around the regime where we will focus today, and in fact the pressure regime we are considering for this work is somewhere right in the middle below and above 3 million times atmospheric pressure so it's a tremendous range to try to access, but we can do it.

arianna gleason: And so we've talked about impacts we've talked about collisions and part of what happens during that impact process is the generation of a shockwave in the material.

arianna gleason: So what is a shockwave well let's think about a train a set of train cars in a row happily.

arianna gleason: moving along, but all of a sudden, the brakes lock on one of the train cars and it comes to an immediate and abrupt stop what does that mean about the train cars behind behind them.

arianna gleason: It will to come to an immediate and abrupt stop and there's a chain reaction of halting of the train cars, this is essentially the same idea.

arianna gleason: As in a shockwave that moves through a sample, it is a supersonic wave that moves through material generating a mechanical or a pressure discontinuity.

arianna gleason: On one side of the shockwave the sample is perfectly happy at ambient condition, on the other side there's a tremendous jump in pressure, and this is what's illustrated in this train car, you have.

arianna gleason: Train cars that are moving forward and train cars that are immediately at a stop. arianna gleason: And the material properties.

arianna gleason: on either side of that shock front, are quite a bit different and it's the change in the material properties that might be the key to template in the appropriate structure for the complexity of materials we're looking at.

arianna gleason: But how do we visualize that a shockwave as you might consider supersonic wave speeds are far faster than we can visualize by looking it using a suite of different cameras so imagine this imagine a horse is galloping.

arianna gleason: And in fact back in the day, there was a bet about how does a horse gallop do all the hooves come off the ground well if you only have.

arianna gleason: The starting image and the final image of a horse you don't have any information about what's going on in between.

arianna gleason: You have A and B, but you don't know what happened in between, so you need a camera you need a set of images or a way to visualize what is going on in between A and B and so to solve this bet that was placed.

arianna gleason: A fellow named Muybridge set a series of cameras and trip wires to track and take images of a horse galloping.

arianna gleason: And in fact you see here in the second and third image all the hooves come off the ground.

arianna gleason: But they wouldn't have been able to satisfy and come to that conclusion unless they had a camera at the appropriate speed and so that's the key here to see the visual is it to visualize the simple molecules breaking and reforming at appropriate timescales, we need a fast camera.

arianna gleason: And so that's why we want to use and can leverage tools here at slac and so I introduced you to LCLS, this is the Linac Coherent Light Source.

arianna gleason: It is an x Ray free electron laser So what does that mean it means it can generate X rays that are laser like in property okay and we'll get to a few of those in just a second.

arianna gleason: But it is essentially a two mile long camera that can zoom in and and have a like you're riding along right with the atom as it's undergoing some dynamic process.

arianna gleason: And it gives scientists, a very unique tool to study a suite of dynamic processes of which this origin of life is just one.

arianna gleason: So a couple terms will come up in the following slides related to timescale Okay, so a nanosecond is about on par with how quickly your computer runs so you may have.

arianna gleason: gigahertz based computer that's about 10 to 100 nanoseconds to process different activities, so a nanosecond is the amount of time it takes light to travel, about one foot.

arianna gleason: However, the X rays produced by the LCLS are a femtosecond so that is a million times faster than a nanosecond.

arianna gleason: it's about the length of time it takes light to travel the width of your hair, so it is the appropriate speed, it is the fast shutter required to witness the chemical dynamics and the materials processes at play.

arianna gleason: And I want to mention also that the the brilliance and the coherence of the LCLS is an aspect that enables this work, so we are able to visualize.

arianna gleason: The changes in the chemistry and the materials that are required, because the X rays have these certain laser like properties okay.

arianna gleason: So we've got our fast camera, but now we have to generate a shockwave, we have to actually bring about that deposition of energy into the system.

arianna gleason: And we do that by using an instrument here at the LCLS and that instrument is the matter and extreme conditions instrument.

arianna gleason: And essentially we bring in high power lasers to blow stuff up and if that's not exciting I don't know what is so this is an opportunity we have.

arianna gleason: To leverage high power lasers and we go through an ablation process which we'll walk through here in a moment, but this is a schematic.

arianna gleason: Of the instrument that that we use and other colleagues use So you see here in yellow the path of the X Ray beam coming from left to right.

arianna gleason: And just above my head is this Chamber, and this is where we place our sample material and where the large lasers come in and interact.

arianna gleason: With our sample and there's a stick person there for size so it's a little it's a bit taller than myself, and it is.

arianna gleason: Appropriate or we are able to crawl inside and place our optics and be engaged in the experiment which I think is really a unique opportunity.

arianna gleason: And this instrument is is critical to a number of different disciplines, not just in shock physics, but also in plasma physics and high pressure mineral physics and warm dense matter.

arianna gleason: So, how does this experiment actually work in the view graph here in the Center of the the image or a set of targets so let's say, these are the the meteoritic material.

arianna gleason: My large laser comes in and, by the way, that laser deposits as much energy, as is in a bolt of lightning and it does that, in a nanosecond or a few nanoseconds So if you recall the.

arianna gleason: movie back to the future and Doc says one point 21 gigawatts well that's exactly what we're doing here in the MEC instrument we send in this amount of energy as much as is in a bolt of lightning.

arianna gleason: And we're going to perturb our sample but here's the best part we get to use newton's third law we're in for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

arianna gleason: So here I show an image of the sample and these two lasers are coming in, here we happen to use to lasers.

arianna gleason: But here we come in and they are incident on the sample and we have newton's third law, which means as those lasers are incident a plasma.

arianna gleason: And ablation process material is blown off as it's blown off these little yellow dots that's my my material blowing off a plasma is forming.

arianna gleason: i'm going to launch a shockwave in the opposite direction in this case the two shock waves are going to come together okay.

arianna gleason: So this process is going to compress instantaneously my material, so our lattice the structure of the mineral will go from ambient conditioned to something highly compressed.

arianna gleason: In nanoseconds and we want to visualize that process, using the LCLS.

arianna gleason: Alright, so we bring in the X Ray being here, I show that a schematic we are we have this compressed material and now here I bring in my X rays, and I probe at just the right time.

arianna gleason: To view what's happening to my sample I then record using a series of diagnostics information about how my structure and sample is changing.

arianna gleason: And then i'm able to do take that information that data and come up with a structure let's say shown in the upper left of exactly how the atoms and molecules are now packed together once they've been compressed.

arianna gleason: So we're going to leverage that kind of tool in three different ways to get it, this question of the origin of life we're going to use X Ray imaging to follow that shockwave that moves through.

arianna gleason: we're going to use X Ray spectroscopy to actually look at the chemistry, how are the bonds between the molecules.

arianna gleason: In the formamide let's say remember that was that key very simple molecule that serves as the predecessor for these potential four nucleobases.

arianna gleason: we're going to look at how the bonds change in real time and, lastly, we will look at how the lattice the mineral structure is modified.

arianna gleason: That perhaps can accommodate the template or the structure required to build up the complexity in those biotic minerals, a material, excuse me.

arianna gleason: So, first we want to visualize and see the shockwave So what do we mean by X Ray imaging.

arianna gleason: Well, you might be familiar with going to the doctor and X rays are passed through some part of your body to visualize perhaps a broken bone.

arianna gleason: it's the same kind of idea that we're using here only our images are taken ultra fast and they use those unique properties of the LCLS meaning the coherence and the brightness.

arianna gleason: And so here I show actually some new data some recent data this data was processed in fact by a graduate student working with Professor Richard Sandberg.

arianna gleason: And here we have we show a sequence of images so when the far corner, we have a sample with a void, so that circular feature in sort of the upper right.

arianna gleason: And it's listed as T equals zero meaning it's time zero it's just sitting there right, so we have a void this example.

arianna gleason: In fact, is not contained formamide in the void, so this is the the no case, so we have a sample.

arianna gleason: From the top of the screen to the bottom of the screen is the shock compression direction so i'm going to send in that drive laser.

arianna gleason: And i'm going to generate a shock right i'm going to generate a tremendous amount of pressure in a very short period of time.

arianna gleason: And so we're going to see as we step through at 2.4 nanoseconds at four and a half nanoseconds and at 8 nanoseconds.

arianna gleason: There are different linear features, you see white lines that move across the are that are located at different positions in the image.

arianna gleason: We are able to track at that nanosecond timescale, the motion of that shock front as it moves through the void.

arianna gleason: So now imagine the next experiment is going to be, we have the void now filled with the formamide material that starting component that could be so critical.

arianna gleason: So this is very exciting preliminary work and we, we have a number of students and postdocs who are working on this topic and we're very lucky to have that sort of opportunity with them.

arianna gleason: So we're able to witness the shockwave move through Okay, but now we want to understand what's going on.

arianna gleason: On the chemical side, we want to understand and visualize how those bonds are being broken.

arianna gleason: and reformed and here we're going to use a different technique, to see that chemical change this is called X Ray absorption spectroscopy so we send in a different kind of X rays and they're called soft X rays lower energy lower.

arianna gleason: Different wavelengths. arianna gleason: And these are just the right energy to interact and give us information about the bonding so we're going to send in that shockwave.

arianna gleason: We want to watch how the bonds how the the the the chemical dynamics are modified during that shock process and we can do that by looking at soft X Ray absorption spectroscopy.

arianna gleason: In fact there's an upgrade coming or in the works, I should say so called LCLS to the Linac coherent light source number two, where we have.

arianna gleason: superconducting Linac, so there are different kinds of linear accelerators to date we've mostly been leveraging copper linac it recently went through an upgrade actually to achieve very hard X Ray energies, but in in concert with that we are bringing onboard.

arianna gleason: superconducting Linac in this will allow us to reach just the right wavelength of soft X rays at bright at the carbon edge, one of the key edges for looking at.

arianna gleason: These carbonaceous complex materials and it's going to get faster So in fact we'll be able to leverage a million pulses.

arianna gleason: per second using this new upgraded linear accelerator so we're very excited for that and we're going to combine that Linac

arianna gleason: That upgrade with dynamic compression so here's a schematic where I show the the Dry laser pulses coming in to a meteorite sample that perhaps has been filled the poor space is filled with the formamide and then we're going to send in those femtosecond those very short.

arianna gleason: pulse length X rays just the right shutter speed right to see the dynamics in process and part of the way we visualize that is maybe a change in the energy, so I show here fluorescence.

arianna gleason: spectroscopy as well, so one color of the X rays coming in, is then modified and that modification that different color tells us something about the chemical change.

arianna gleason: And finally, we, we need to understand what's going on with the host rock materials so we visualize the shockwave.

arianna gleason: we've looked at the chemistry, and now we want to understand the contribution of the mineral structure change to the template right, how is the material modified and a way to track that.

arianna gleason: A way to fingerprint, if you will, how minerals are being modified how the structure is changing, is by using something called X Ray diffraction.

arianna gleason: And so, here again just the right wavelength just the right energy of X rays, are going to come in and interact with the periodic array of atoms so called this lattice structure and when that lattice structure changes, we will see.

arianna gleason: A different pattern arrive on our detectors and every single mineral every single one has a different.

arianna gleason: structure, in other words there's a unique fingerprint for every single one, so I can track that I can visualize that fingerprint change, as it were, in real time.

arianna gleason: And so we've done this in the past, some studies have been completed, looking at silica looking at quartz and you might be familiar with this in fact.

arianna gleason: The majority of the rocks vast majority the rocks here on the surface, are silicate felled spars the number one only second to two quartz.

arianna gleason: And so we can collect this as our starting material and watch how the structure changes in real time.

arianna gleason: And in fact we've seen how the bonds of the silicon and the oxygen in the silicate are broken and reformed.

arianna gleason: At sites such as an impact site where you can scoop up material and say Oh, you know what I find here I find a different structure that's indicative.

arianna gleason: Of a high pressure event, and I can watch that take place using these high powered lasers, to generate the shock.

arianna gleason: And we've done that so here's an example of a study, where I have a sample of quartz or a few silica so called window glass, as it were.

arianna gleason: And we send in just the right amount of energy to generate a shockwave and when that shockwave is moving through our sample I probe with LCLS at just the right time.

arianna gleason: And so let's see an example of that Oh well, first let's take a tour of how we do that experiment here is the MEC Chamber so, in fact, the.

arianna gleason: The location where you can go in and position your optics there's a target.

arianna gleason: Stage right in the middle and we have our cameras downstream and, in fact, for some of these optics these laser optics are four inch massive optics us to focus.

arianna gleason: Different parts of the optical laser so again very exciting stuff for all you young researchers out there here's the Chamber as it, as it were, again.

arianna gleason: A little person there for size so it's certainly taller than me but big enough, so I can get in and crawl around.

arianna gleason: And here's an example of a photograph of the inside, so imagine you're able to crawl up in there and position your different optics In fact I saw colleagues and friends of mine doing that just today inside the MEC Chamber so it's a very active place where we can we can.

arianna gleason: manipulate and place our diagnostics and cameras, as we need so here's an example of a starting material, this is fused silica.

arianna gleason: And the take home message is that there's actually not much to see fused silica is amorphous meaning it's a disordered structure.

arianna gleason: So that fingerprinting capability looking for a specific pattern of intensity on a camera.

arianna gleason: We actually expect to not see any just above my head, you might see some black sort of pepper speckle patterns, this is damage on the camera.

arianna gleason: And so, here we have our fused silica it's just sitting there at ambient condition and i'm going to send the laser in.

arianna gleason: i'm going to generate a shockwave and then i'm going to probe at just the right time and what happens oh this beautiful pattern.

arianna gleason: is collected So what does this tell me it tells me that my structure my fused silica my glass the bonds between the silicon and the oxygen are breaking.

arianna gleason: and reforming so called a reconstructive phase transition, and this is happening in real time and only a few up to 12 nanoseconds as I show here okay.

arianna gleason: So this is the kind of work that will be completed to study to look at the origin of life, these three key aspects, the imaging of the shockwave.

arianna gleason: That tells us how is the surrounding material modified, how is that shockwave modifying the the meteorites sample.

arianna gleason: We want to understand the dynamic chemistry at that pore space where we're holding our formamide.

arianna gleason: How are those bonds breaking and reforming and on what timescale we suspect based on previous work that in fact there's a critical missing data set at very short times, where the most exciting chemistry is taking place, we need to see that we need to visualize that and, finally, the third.

arianna gleason: aspect of this is how is the mineralogy changing, how are the minerals influencing that kickstart of life that required structure of the.

arianna gleason: nucleic acids that that are formed. arianna gleason: And with that I want to then step back and realize that these processes are taking place.

arianna gleason: All over our solar system likely all over the universe, and this is an extraordinary time to be living in here we have sample return.

arianna gleason: Coming back from Mars, there are so many opportunities there and exciting new data sets coming in from different Rovers in this in the studies that are undergoing.

arianna gleason: For Mars other icy moons of different different planets here's a visual of Enceladus, which is an icing moon of Saturn that has this beautiful so called chaos.

arianna gleason: structure these these cracks these linear features that actually, let us know that there's liquid water there's water below the surface.

arianna gleason: And so there's so much opportunity for that required molecular component that that opportunity for the basic building blocks of life.

arianna gleason: And through these shock compression through the dynamic high energy processes of collisions we have that energy input to build up complexity.

arianna gleason: and, moreover, I think the other piece that we're trying to focus on is how to provide the template how to provide that blueprint and the minerals themselves might be the key.

arianna gleason: So this is an extraordinary time to be a scientist and we are very lucky to have access to the tools, but there's more to be done so, a message to to the listeners out there is this is so.

arianna gleason: important for you to get engaged ask questions there's lots of opportunity for participation and I really encourage you to reach out.

arianna gleason: To to your your your friends your colleagues and try to get engaged if you're if if it if it suits you and with that i'd like to leave you with this thought.

arianna gleason: You know the the history of humankind is marked on a timeline of discovery and I think this is what's next.

arianna gleason: And with that i'd like to acknowledge my extensive fantastic collaborators here I list several names many names, but there are many more, and in particular.

arianna gleason: colleagues here at slac who are just critical to the execution of so many experiments colleagues at Stanford in the extreme environments laboratory.

arianna gleason: Many institutions both across academia and national laboratories play a monumental role in enabling these team large team activities and, certainly, I want to acknowledge my funding.

arianna gleason: Lots of this work is spurred on by the Department of Energy office of science, as well as NSA and certainly the National Science Foundation.

arianna gleason: And with that I will conclude the main part of the talk and i'd really like to introduce to folks who are highlighted here.

arianna gleason: Dr Richard Walroth and Professor Richard Sandberg, so we are fortunate enough to have two Richards.

arianna gleason: With us today good friends and colleagues of mine and a little bit about each one of them, Dr Richard Wolroth here works here at slac and now an LCLS.

arianna gleason: Project scientist staff scientist, but he hails from NASA so he previously worked at NASA and currently much of his work is focused on looking at at lunar regulus and using spectroscopy to study.

arianna gleason: Those materials, I also want to introduce Professor Richard Sandberg.

arianna gleason: He hails from the Department of physics and astronomy at brigham young university but prior to that he was a prominent member.

arianna gleason: At the Los Alamos national lab worked on an extensive set of shock compression studies and is an expert in X Ray optics and looking at.

arianna gleason: Not just materials that extreme conditions, but the the fundamental tools required to visualize that and with that, I think we will transition to the panelists Thank you.

michael peskin: Well Ariana thank you very much it's a really fascinating lecture um let's just get rearranged I think you have to share your screen and we'll go to a gallery view of the three speakers.

arianna gleason: sure.

michael peskin: And so Carmen, you can arianna gleason: There we are Thank you.

michael peskin: There we go okay very good so now we'll have ariana Richard and Richard answering questions if you i'm sure you have more questions.

michael peskin: So please now look at the bottom of your zoom screen there's a Q&A, type your questions in there and we'll answer them, in turn, as long as we have time.

michael peskin: So actually here's, the first question. michael peskin: Yes, um. michael peskin: We all know that you can pick up a rock and say whether it's you know from your sixth grade experiences sedimentary igneous rock it came from sediments or came from volcanoes can you pick up a rock and say this must have come from meteor?

arianna gleason: that's a that's a wonderful question and I think it's it's all about the location of the fall, as it were, I know that in a number of experts collect.

arianna gleason: meteorites and other falls in strategic areas such as the poles right Antarctica and you can easily see where rocks have fallen that are clearly out of out of place.

arianna gleason: There are other ways to test different rock rocky materials and by looking at their isotopes and so for a lay person to or.

arianna gleason: An individual to pick to pick up a rock and claim, without a doubt that it's a meteorite I think there's probably only a few cases where that would be appropriate, one of which is if it's an iron meteorites so it's it's just iron nickel rich highly magnetic.

arianna gleason: That might be a clear, a clear path, I wonder if Richard Walroth do you have other comments there on that one.

Richard Walroth: No, I think you captured pretty well it's it can be very difficult to tell me, I said something is meteorite, but there are certain clues are certain classes meteorites like Pallasites which are so distinctive that they're obviously from meteorite origin but.

Richard Walroth: largely speaking, you know, there are missions, where people go out to find them and if you're jealous to notice about them and know that this rock has no business being among a specific formation, but in general.

Richard Walroth: places like Antarctica are great because it's all going to be ice unless you have the meteorite is coming from somewhere else so that's one of the reasons by NASA loves to go to Antarctica source, a lot of meteorites.

michael peskin: Okay, very interesting um someone out there would like to know um are there flat planets.

arianna gleason: Ah, no, maybe arianna gleason: Richard Richard Sandberg do you want to go for that one.

Richard Sandberg: yeah I actually looked this one up a little bit, so the international astronomical Union right, you may have heard about their definition of planets which they read us redefined Pluto is a dwarf planet.

Richard Sandberg: And one of those is that the planet is big enough, it has enough mass that its gravity kind of squished as it into a circular object or a spherical object.

Richard Sandberg: So, I guess, technically, something that was flat kind of like that that meteorite was at El Hammami I can't remember the long skinny one that was coming out.

Richard Sandberg: That one technically is not a planet because it's not big enough it's not orbiting the Star and clearing there's several definitions of a planet but I guess, we would say it's not really a planet if it's flat.

michael peskin: You agree with that already though i'm not a planetary. michael peskin: yeah you have to remember the Earth is flatter than a Bowling ball it's more spiritual than a Bowling ball.

michael peskin: So um when you have something that big gravity just pulls it all into the most compact shape.

michael peskin: And when the planets form they were very hot, so it was even easier. michael peskin: But the asteroids have crazy shapes sometimes you've seen them.

arianna gleason: They do yeah we've seen I recall a variety of photographs some that are shaped like peanuts, so I think there are certainly different shapes but it's true as.

arianna gleason: Professor Sandberg said, you know the ones that sort of self gravity different forces at play encourage more of a spherical structure, Sir yeah like a ball structure exactly.

michael peskin: Andre Antoine would like to know, has there been any evidence to support the possibility of non carbon based life supporting chemistry, so you talk to me about carbon based chemistry.

michael peskin: that's right. michael peskin: I guess there isn't much evidence, one way or the other but please Is this a possibility that we should think about.

arianna gleason: Probably Dr. Walroth has more insight on that question.

Richard Walroth: To my knowledge there's not been any definitive demonstration, you can have a silicon based chemistry to support life, it comes down to you know there's a.

Richard Walroth: From the chemistry respective you have to have the right energy for bonds breaking and forming so that you can actually synthesize complex molecules and then have them stick around for a long time to actually serve as something for life so on the sort of like a.

Richard Walroth: Narrow zone for at least on earth now, there has been some proposals, for example, nitrogen based chemistries for life on place like titan because it's so cold that you can actually form these sort of stable complexes formed purely with nitrogen nitrogen bonds.

Richard Walroth: Though again that's you know whether or not they actually give rise to life, you know, theoretically, we say something complex can form but life is so complicated that it would be very hard to model it.

Richard Walroth: Just the theoretical basis so short answer experimentally, we haven't seen anything theoretically there might be some other chemistries that there's some indication could work, but they have not yet been demonstrated to experimentally, the valid percent for forming complex life.

michael peskin: Bob Millen actually first of all, really enjoyed the talk, thank you very much he'd like to know about two other sources of energy that might play a role, first of all cosmic rays, and secondly, solar UV radiation.

michael peskin: Are those part of the picture or not. arianna gleason: I think actually Richard has done you've worked a bit on the UV or not worked a bit, but considered the UV input energy option right.

Richard Sandberg: yeah so UV is definitely something that's producing a lot of chemistry in our atmosphere, you know the ozone layer you you've heard a lot about is being formed by.

Richard Sandberg: Mostly ultraviolet and shorter wavelength light that's got a lot of energy up there, so I i'm not an expert in that area, but I definitely heard that that is a source that people have talked about.

Richard Sandberg: Cosmic rays I don't know that those are very, very high energy there's there's cosmic rays that are.

Richard Sandberg: You know many, many, many times more energetic than anything we can produce here on on earth, and so I don't know if that would.

Richard Sandberg: Would kind of you know tailormade take apart these bonds, so they can go back together or just kind of blow everything up, so I haven't heard a lot of discussion about cosmic rays, but.

Richard Sandberg: Maybe Richard Walroth or Dr gleason know more about that, but ultraviolet i've definitely heard about that chemistry in the upper atmosphere.

Richard Walroth: I have not heard of cosmic rays, leading to this, I mean.

Richard Walroth: They were definitely in part a lot of energy inconsistent, so if you have some molecules they're going to break them apart, and we know that they can recombine and form some very interesting compounds.

Richard Walroth: Like one of the things that Dr Gleason was talking about in her talk was this idea of you know, after an impact you from this plasma you get all these fragments new combined so cosmic Rays could probably produce the same types of conditions.

Richard Walroth: it's but you know they're very hard to produce in the lab they're so highly energetic that that's you know, so we have a hard time modeling does this perfectly, but presumably they are forming these kinds of alterations in the interstellar space or not sorry an interplanetary space.

michael peskin: Bob would like to know if you can relate the energies created by impact, so the energies and your experiment is you're trying to reproduce this level of energy or you're in a different sphere.

arianna gleason: No, in fact, the the level of energy deposited into the system and the time scale are a one to one, so they are in fact the same there's some discussions on do you need.

arianna gleason: So called laser induced dielectric breakdown, as in the the the Ferris et al article so like truly generating a plasma of the material and then the the the three.

sort of a. arianna gleason: build up then of the more complex molecules or if the passage of a shock in the context of several 10s to hundreds of GPA so that's you know.

arianna gleason: 10 to the 9 pascal's of enter of high pressure, but also many thousands of kelvin's 3000 5000 kelvin and you do all of that in just an instant.

arianna gleason: And it turns out that the energy relationships are quite quite on par at least from a from a modeling perspective so so we feel confident we can achieve that kind of energy deposition here with our tools.

michael peskin: Okay, Joe would like to know about this business of chirality that you brought up, are you aware of any solid surfaces in nature that favors left handedness as opposed to right-handedness or vice versa.

michael peskin: Could we have life, based on D, instead of L amino acids. arianna gleason: I love that question, you know I by trade, I am not a biologist or really a chemist, as it were.

arianna gleason: But I have done some reading on this and it's actually quite fascinating I think the answer is, we don't know I don't think we could some of the minerals in the structures that have been put forth to.

arianna gleason: Encourage differences in chirality or clays so one, one that was mentioned quite a bit is so called Montmorillonite, and this is a clay mineral that actually is quite common when we produce.

arianna gleason: Cement so some of the materials, of which the buildings are made in fact have the appropriate structure it's in fact a very layered structure of the silicate and depending on the slight differences in the this layered orientation, it could be possible, I think more.

arianna gleason: More step by step, studies more sort of visualization at that level of the appropriate level.

arianna gleason: Of this lattice are required to answer that for the other aspects of the chirality question, I wonder if Dr Walroth has some more insight on that.

Richard Walroth: um. Richard Walroth: Yeah I think you covered very well you know how we can see how these things make a template in terms of you know, could we have life, based on d amino acids.

Richard Walroth: From a chemistry standpoint, the answer would be yes, but it would just have involved everything being the I mean the.

Richard Walroth: So the idea of chirality is that it comes from the term handedness, you have a left hand and right hand and you know.

Richard Walroth: All of our amino acids all conform to one of those two but in principle the other.

Richard Walroth: An enantiomer is called is chemically identical in fact separating out to an antivirus from each other, is a very difficult thing to do, because they are chemically identical so you have to find.

Richard Walroth: lots of different ways to do it it's very important for like developing medicines, because they have to be an edge America with pure So yes, there's.

Richard Walroth: chemically nothing stopping it from having gone the other way and there's a standing question and pretty bad chemistry, why did we go with l amino acids, instead of d like, why did that become the dominant form and.

Richard Walroth: I don't believe that question has been definitively answered yet. michael peskin: Yeah I just gotta jump in here, you know i'm not in this field, but i'm an elementary particle physicist and i'm kind of an expert in chirality and elementary particle physics.

michael peskin: And so, in ordinary chemistry there's a symmetry that says, if you have a left handed structure and a right handed structure, they just have the same chemistry they're just mirror reflections of one another.

michael peskin: On the. michael peskin: It turns out that the radioactive decay is actually chiro and there are a bunch of papers trying to prove that were left handed because of that.

michael peskin: Personally i've read those papers and i'm not persuaded but it's still something that people debate, but the thing you have to think about is evolution.

michael peskin: Once you have a successful kind of protein which is left handed then it grows exponentially and it pushes out all the unsuccessful right handed ones, or vice versa, and I think, personally I think that's the most reasonable explanation, it could have gone either way it's just a coin flip.

michael peskin: um. michael peskin: Let's see Ferguson, would like to know, can you talk a little about the caching of samples being taken by the MARS perseverance and when they will be accessible for further analysis.

arianna gleason: Oh that's a great question I don't happen to know i'm actually going to delegate that to Dr Walwoth who who may know more on the NASA side.

Richard Walroth: So I was actually fortunate to be at a conference recently where they're talking about this very question.

Richard Walroth: And the answer is that the perseverance rover is going to go around a special caching system for drilling and storing samples within the Rover and then there's going to be a separate batch mission, so the perseverance Rover did not land with the way to get back.

Richard Walroth: And the reason for that is, we want to take our time collecting samples liking your samples are the best ones.

Richard Walroth: And in that time sort of rocket fuel being a high energy substance actually doesn't stay good for very long, it has an expiration date.

Richard Walroth: So you want to land a rocket and launch it as soon as you can it already has to survive the trip to Mars, so the idea is that once the rovers finish caching 11 samples, which could be.

Richard Walroth: I don't know how many years it's expected to take there will then be a second mission to bring them back and that one's going to be done by the European Space Agency.

Richard Walroth: And so it's going to be a few years before that would launches I don't know if they've set a launch window for it.

Richard Walroth: But yeah it's it's going to take a while, the perseverance rover just landed i'm not sure if they even cach to their first sample yet, but.

Richard Walroth: they're going to take their time they can analyze the it carries a feat of analytical techniques to make sure that.

Richard Walroth: samples are going to carry the most sense they're going to be extremely extremely difficult to get back from Mars, so we want to make sure that wants to do bring back our worth the worth the effort.

Richard Sandberg: I just googled an article and it said 2031 was about the earliest time they thought they'd be coming back so.

Richard Walroth: That sounds about right. michael peskin: Okay Scott, would like to know what are the outer limits of temperature and pressure at which we think life could persist.

michael peskin: Recently I haven't checked this there was rumor about tardigrades not being tough enough to survive falling through the atmosphere, what are the prospects for simpler life surviving a journey from one planet to another carried by this cosmic uber that Arianna talked about.

arianna gleason: Um let's see what a couple different points to make, there I think some of these uber's are there, different sizes and so you can actually carry material from one.

arianna gleason: place to another if it's large enough and during the re entry or the entry process through through an atmosphere, such as our earth's atmosphere, it does cause quite a bit of degradation.

arianna gleason: Certainly there's a shock layer that forms for over 30, 40 minutes, and that will.

arianna gleason: Essentially disintegrate parts of the of the material, but we have proof that.

arianna gleason: Some of that material survives and continues to fall and then, and then we find it, so I think there are different ways in which the actual host material the the meteorite or the rock and the minerals themselves.

arianna gleason: Are are up to the task, first of survival in terms of temperature or pressure conditions out if the extreme edges, maybe of our solar system and the like.

arianna gleason: it's a pretty inhospitable place it's it's cold, I wonder if, maybe Dr. Walroth has a better idea of sort of the in the the the outer solar system what what the conditions are there, I think the simple maybe prebiotic materials can.

arianna gleason: exist quite quite easily, but it really is through this insertion of some energy source to to build up something more complicated, you need a process I don't know Dr. Walroth do you want to comment.

Richard Walroth: Um so this question is on survivability of life. Richard Walroth: And life can actually be pretty Sturdy and then it's a question of you know.

Richard Walroth: What counts as survival like if it's a bacteria that's fragmented, to the point that it's you know, maybe it itself is not necessarily alive anymore, but it can also see the growth of new things which can feed off of it.

Richard Walroth: In terms of life forming it's a question of scale as well, like you just have a small meteorite which happens to have some liquid water and some sort of like maybe something's decaying radioactively only providing some heat.

Richard Walroth: But it's such a small thing that it's only going to have very few reactions going need sort of like it's.

Richard Walroth: As far as we know, it's a game of chance, so you need a large volume of reactions all on going to have a larger large enough chance to produce the spontaneous formation of life.

Richard Walroth: Also, in terms of life surviving the trip. Richard Walroth: We know that the core of a meteorite can actually stay pretty cold surprisingly has it descends through the atmosphere.

Richard Walroth: So it's entirely possible if there's like a very large enough be right that it doesn't completely.

Richard Walroth: evaporate in the atmosphere, then you know who knows it could be possible that some chunk of that flies off and loses enough speed that doesn't impact, I mean we.

Richard Walroth: pick up these meteorites and there you know you can find them and see them in museums and stuff and they're you know they're not all turned into dust so couldn't be said something in the core of all of those survives but.

Richard Walroth: Probably for that turned out to be life outside of the earth that's a different question so.

Richard Sandberg: Can I just jump in there, I see a couple of questions that maybe this kind of all touches on about.

Richard Sandberg: Is the main theories still that ocean that life is developing an ocean and and I correct me if i'm wrong, but I think what what we're saying is that on these meteorites these uber's might be delivering.

Richard Sandberg: The ingredients of life or the building blocks of life but it's not a very common hypothesis that you know coronavirus or some bacteria is living on.

Richard Sandberg: A meteorite that then lands on earth and that seeded life we're talking more about chemistry occurring to produce the building blocks, but then we believe through those evolutionary processes in the oceans or bodies of water that's where it's happening is that correct.

arianna gleason: Yeah I believe so, Richard Walroth is probably more expert than myself, but I think there's another piece here as well, in the impact process itself and.

arianna gleason: Then the the the remnants or the modification of the surface during that impact event there's a there's a lot of opportunities there.

arianna gleason: Especially for for key mineralogy to play a role, and then you build on top of that opportunities for these these.

arianna gleason: Micro organisms that are happy with extreme conditions right these extreme of files and so you can sort of have a combination of these sequences take place that then promotes more more opportunities yeah.

michael peskin: Okay, Yuli would like to know um how do these spatially relatively loose bunches of electrons from the Linacproduce much tighter X Ray pulses from the LCLS.

michael peskin: What is the magic that compresses the X Ray pulses. michael peskin: And what is the scale of compression.

arianna gleason: That is a great question, I think, Professor Sandberg is is is key to answer that one.

Richard Sandberg: i'm excited chances. arianna gleason: Are you know I know. Richard Sandberg: it's thanks Yuli that's a great question and that's one of the I won't call it magic but that's the word I want to use about these X Ray free electron lasers.

Richard Sandberg: Is you get like you, you describe this kind of loose bunch of electrons that in in science, would call it it's kind of their incoherent they're all doing their own thing.

Richard Sandberg: Except they're all traveling along this long accelerator like Dr gleason showed it near the speed of light very near the speed of light like 99.999% the speed of light.

Richard Sandberg: And then we pass them through this these magnets that jerk come back and forth, and as we do that they're accelerating and when we accelerate electrons they produce light.

Richard Sandberg: And now, this light is starting to interact with the charged particles and it's that interaction of the light with the charged electrons.

Richard Sandberg: which then starts, causing the electrons to start going towards the the the peaks and the troughs it's actually not the peaks and troughs but it's the peaks and troughs in that light wave start pushing the electrons together.

Richard Sandberg: And so the electrons start self organizing and it's a feedback of the the X rays that are produced on the electrons which then causes the electrons.

Richard Sandberg: To produce X rays that are more laser like and so it's this really beautiful feedback and.

Richard Sandberg: It builds up exponentially and it's a lazing process, the technical term is called self amplification of spontaneous remission so those first X rays that are generated are kind of spontaneous.

Richard Sandberg: But then they caused the electrons as they interact over this really long magnetic array called an undulator, it's about a football field long and that's what causes the the electrons to get squished together and organize and produce laser like X rays.

michael peskin: Yes, very early in the series when the LCLS first turned on, we had a lecture on how the LCLS works, the title was zap the X Ray laser is born.

michael peskin: it's actually a great lecture and if you go to the slack website, the public lectures website and click on past lectures, you can look it up.

michael peskin: So i'd recommend probably we should have another lecture like that, now that that was 10 years old, to tell you about what's happened in the meantime, but that's a whole nother question.

michael peskin: I'm going to allow a softball question have arianna.

michael peskin: I would like to know if we can reach the plasma stage of matter using lasers, how much additional energy would it required to reach the nuclear fusion stage.

michael peskin: And could this actually play a role in biology, I think the answer that last question is no but the first one has an interesting answer.

arianna gleason: Yeah the second part is is probably no, but I think.

arianna gleason: deposition of energies, much like what we have leveraged at the NIF so there's the the national ignition facility here, also in the in the Bay area at the livermore national lab so there they use 192 lasers all pointed at essentially just the tip of a pen and this.

arianna gleason: With very strategic targets your sample materials, you can actually start this this process this mimicking the interiors of a star and so here at slac.

arianna gleason: One thing that we're looking forward to for the the MEC the matter in extreme conditions hutch is in fact an upgrade in our lasers our dry lasers, of which I really just mentioned one or the to generate the shock waves.

arianna gleason: But there are other tools other types of lasers that can be leveraged. arianna gleason: So called short pulse lasers that actually deliver higher intensity in a different spatial regime, so you you generate these plasmas.

arianna gleason: And I think that there are a couple opportunities we're looking forward to as a Community where key upgrades two parts of our laser system here will get us to that that next step, and then we can actually do.

arianna gleason: Maybe some of the experiments you're thinking about in our in our upgraded laser facility, I know that also Professor Sandberg is playing a key role in.

arianna gleason: Having the Community be active and aware in this possible upgrade opportunity.

Richard Sandberg: Yes, this is actually a screenshot of a rendering behind me of the proposed upgrade to the matter and extreme condition hutch

arianna gleason: I didn't know that. Richard Sandberg: yeah sorry I just I got. Richard Sandberg: From Alan I don't know if he's still on. Richard Sandberg: But yeah.

Richard Sandberg: So we're really excited about that and the MEC has really changed a lot of our understanding.

Richard Sandberg: And there's I think more than a handful of facilities around the world that have kind of jumped into that game now in Germany and Japan and Korea, China.

Richard Sandberg: Where they are trying to improve upon or duplicate the results at MEC and so there's there's kind of this race now to see who can combine these really brilliant X rays with these.

Richard Sandberg: Higher energy and denser states of matter, and so the mec upgrade would be really exciting a big push forward for the United States high energy density physics community and a really big improvement for slac so we're we're hoping it happens on the order the next five to seven years.

michael peskin: Okay, so let me ask you now a final question, and this one is maybe more philosophical, but you might have something to say about it.

michael peskin: Someone wants to know does this work, help us to understand the other aspect of life that we're extremely interested in now.

michael peskin: Namely the effect of climate change and the impact of human behavior on climate change, so this person asks how can the search to understand the origins of life, help us to take better care of the life on this.

arianna gleason: Oh that's that's a wonderful question. arianna gleason: I think part of part of the answer, there is really engaging in the appropriate scientific studies to visualize these fundamental chemistry and physics.

arianna gleason: Experiments that tell us the story of that of that sequence, as it builds up to form possible life.

arianna gleason: We in the climate change aspect is is one in which we can monitor now unfortunately in real time in a number of ways, how our environment is being modified by by our activity and we can actually zoom in on some of those you know changes in the chemistry.

arianna gleason: and changes in biology that we see as a consequence, and again it's really coming down to some of those fundamental physics and chemistry studies that enable us to see all you know we did wrong here, or you know what the consequence of this.

arianna gleason: You know process that maybe we kick started is modifying the the biology in the following way and so it's a visualization.

arianna gleason: sort of revolution that we can actually see and distinguish these now and hopefully it will help us do a better job.

arianna gleason: Protecting the life that that that that we have here i'd also like to give maybe both a Dr. Walroth and Professor Sandberg an opportunity to pitch in here, maybe Dr. Walroth first.

Richard Walroth: yeah. Richard Walroth: I think it's all that you said and um.

Richard Walroth: Yes, definitely I definitely wouldn't say it's directly related to work on climate change or how to prevent it.

Richard Walroth: understanding this you know, there are some. Richard Walroth: Like looking at, you know how these things form and these types of plasma events.

Richard Walroth: it's related in some ways to types of reactions that happen in combustion, which is, you know how we still derive a large portion of our energy.

Richard Walroth: And could potentially you know if we can close the carbon loop, and some people like me at can recapture CO2 and turn that back into fuel.

Richard Walroth: So understanding that chemistry, in these conditions, might you know, help us to understand chemistry these other ways, and there is work I believe we're done at LCLS looking at combustion, which is.

Richard Walroth: itself a very complicated process you don't think of it, but the chemistry happening in your car engine is actually not.

Richard Walroth: That well understood so maybe we can find ways to be more efficient and reduce your carbon footprint that way, and then this provides just a new way for us to you know.

Richard Walroth: sort of synergistically understand the origins of life, and also how to have practical applications.

Richard Sandberg: Yeah, just to build on on Richard and Ari's comments you know the the the understanding of this high energy density state may not directly tie into climate change, but a lot of the work done it the national labs is.

Richard Sandberg: Dr. Walroth mentioned some there i'll just mention a lot of the work done at NBC and some of the big motivation for the upgrade.

Richard Sandberg: is to understand fusion energy and if we can master that and get that working, that will be essentially.

Richard Sandberg: limitless clean energy, which could make a huge dent we could drastically reduce our dependence on fossil fuels if we can get fusion energy working.

Richard Sandberg: So that is definitely related with this this matter and extreme condition and I guess just for me personally understanding how.

Richard Sandberg: intricate the origins of life is makes me personally appreciate it more and want to take more personal care of it right to do my part to make sure.

Richard Sandberg: That we are preserving and protecting life here, because we can see how quickly species can disappear when we don't get them back so.

Richard Sandberg: So yeah I think when I when I studied the origins of life or think about that process and think it could be coming.