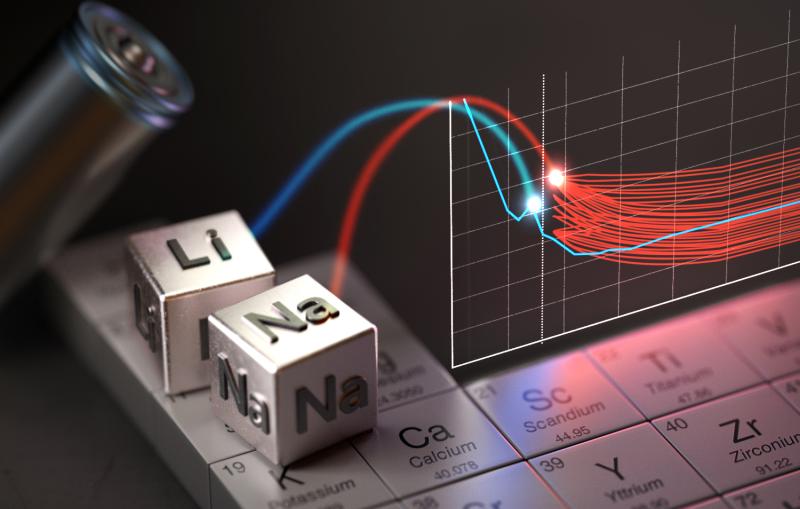

How extreme cold can crack lithium-ion battery materials, degrading performance

Storing the rechargeable batteries at sub-freezing temperatures can crack the battery cathode and separate it from other parts of the battery, a new study shows.

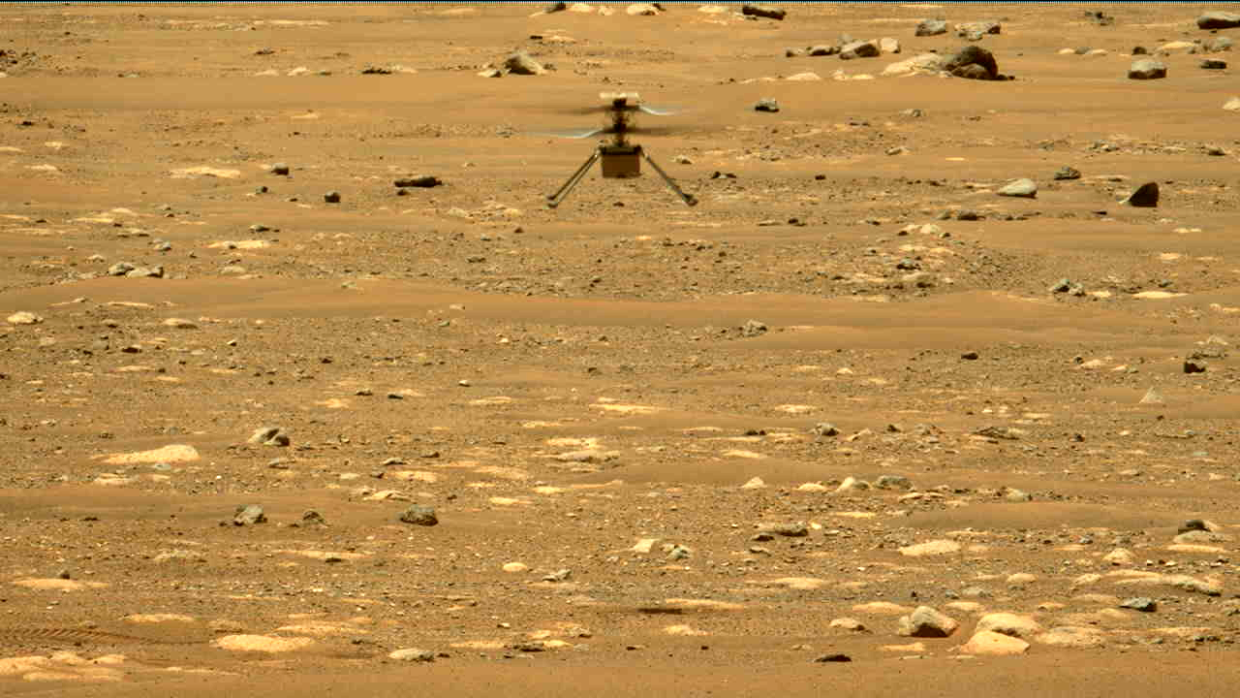

Lithium ion batteries are a bit famous for their poor cold-weather performance, and that has consequences for some of their most important applications – everything from starting an electric car in a Wisconsin winter to flying a drone on Mars.

Now, researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have identified an overlooked aspect of the problem: Storing lithium-ion batteries at below-freezing temperatures can crack some parts of the battery and separate them from surrounding materials, reducing their electric storage capacity.

SLAC scientist Yijin Liu and postdoctoral fellow Jizhou Li made the discovery while looking at the cold-weather performance of the cathode, the part of the battery electrons flow into when it’s in use. Initial studies found that storing cathodes at temperatures below zero degrees Celsius led batteries to lose up to 5% more of their capacity after 100 charges than batteries stored at warmer temperatures.

To understand why, the researchers turned to a combination of X-ray analysis methods at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and machine learning techniques that Li has been working on over the last several years. The combination allows them to identify individual cathode particles – meaning the team could study thousands of particles at once, compared to just the handful they could identify with their eyes alone.

Together, those methods revealed that cold temperatures were shrinking the meatball-like particles within the cathode and in the process cracking them – or making existing cracks even worse, Liu said. And, since materials differ in the way they expand and contract in response to changing temperatures, extreme cold was also detaching the cathodes from surrounding materials.

The results point to some possible fixes, Liu said. By looking for battery materials that are better matched in terms of their temperature response, scientists could address the detachment issue. Doing so could help improve other batteries as well, since all batteries expand and contract as they heat up and cool down. And by engineering different particle structures inside a battery – notably, building them up from smoother, less meatball-like particles – researchers could help prevent cracking and improve long-term lithium-ion battery capacity.

The research was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation. SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: Jizhou Li et al., Advanced Energy Materials, 21 August 2021 (10.1002/aenm.202102122)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.