Cryo-EM study yields new clues to chicken pox infection

Stanford and SLAC scientists studying the varicella zoster virus found that an antibody that blocks infection doesn’t work exactly as they’d thought.

Despite decades of study, exactly how herpesviruses invade our cells remains something of a mystery. Now researchers studying one herpesvirus, the varicella zoster virus (VZV) that causes chicken pox, may have found an important clue: A key protein the virus uses to initiate infection does not operate as previously thought, researchers at Stanford University and the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory report August 18 in Nature Communications.

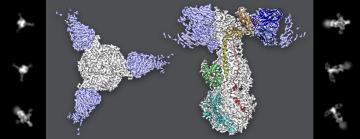

The results were made possible by high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which showed that the immune system can prevent infection by attacking a spot on the protein in an unexpected place, said Stefan Oliver, a senior research scientist in pediatrics at Stanford and the new study’s first author.

Herpesviruses including VZV – along with HIV, coronaviruses, and a number of other virus families – are enclosed in a protective membrane, and the first step in the process of invading a cell is for the viral envelope to fuse with the cell’s membrane. In VZV’s case, a protein called gB that sits on the outside of the viral envelope uses a set of molecular fingers to grab onto and fuse with cells.

But it turns out that’s only part of the story. To investigate what was happening in more detail, Oliver and colleagues used an antibody from a patient that prevented VZV fusion with cells in cryo-EM experiments to discover where the antibody attacks gB.

To Oliver and colleagues’ surprise, the antibody bound to a spot on gB far from the fusion fingers, indicating that it may not need to target the fingers to prevent fusion with a cell. This result suggests that there may be more involved in the process of fusion, which causes infection, than was realized.

Figuring out exactly how the fusion process works will take further studies that could inform the design of treatments and vaccines for other herpesviruses, Oliver said, since they also rely on gB to infect cells. “Vaccines are currently not available for herpesviruses, with the exception of the one that prevents VZV, so the development of vaccines that target this newly identified region of gB has the potential to solve an important medical need.”

Oliver added, “It was only possible to uncover this mechanism by generating one of the highest resolution structures of a viral protein-antibody pair using cryo-EM. Without the cryo-EM capabilities at SLAC these fascinating insights into the molecular mechanisms of fusion function would not have been achievable”.

Cryo-EM studies were conducted at the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Facility. The research was funded by the Stanford Bio-X Interdisciplinary Initiatives Program and the National Institutes of Health. The paper’s senior authors were Ann Arvin, a professor of pediatrics and of microbiology and immunology at Stanford, and Wah Chiu, a professor of photon science, of bioengineering, and of microbiology and immunology.

Citation: Oliver et al., Nature Communications, 18 August 2020 (DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-17911-0)

Content

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

(Image Credit: Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)