Researchers map out intricate processes that activate key brain molecule

For the first time, scientists have revealed the steps needed to turn on a receptor that helps regulate neuron firing. The findings might help researchers understand and someday treat addiction, psychosis and other neuropsychological diseases.

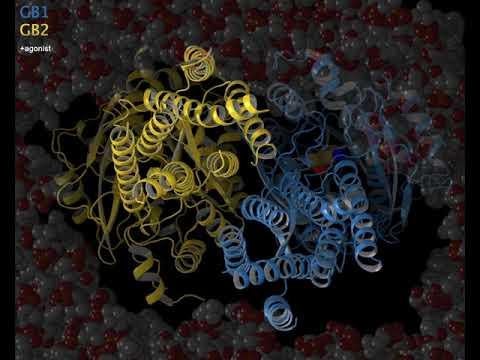

GABAB receptor

For researchers looking to understand and someday treat certain neuropsychological ailments, one place to start is a molecule known as GABA, which binds to receptor molecules in neurons and helps regulate neuron firing rates in the brain. Now, researchers have produced a detailed map of one such GABA receptor, revealing not just the receptor’s structure but new details of how it moves from its inactive to active state, a team writes June 17 in Nature.

Scientists have never seen such details before in a human receptor, said Cornelius Gati, a structural biologist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and a senior author of the new paper. Information about the structure of the molecule and its transitions between states could help scientists better understand GABA receptors and may help chemists design better drugs to treat addiction, psychosis and other conditions.

Scientists have never seen such details before in a human receptor, said Cornelius Gati, a structural biologist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and a senior author of the new paper. Information about the structure of the molecule and its transitions between states could help scientists better understand GABA receptors and may help chemists design better drugs to treat addiction, psychosis and other conditions.

GABA, short for gamma aminobutyric acid, is central to our brains’ proper functioning. When released, it binds to neurons at one of two receptors, GABAA and GABAB, and slows their firing rates. Drugs that mimic GABA generally have a calming effect – the tranquilizer benzodiazepine, for example, works by binding to GABAA and activating the receptor.

In the new study, Gati and colleagues focused their attention on GABAB, using cryo-electron microscopy to take detailed pictures of the molecule. The technique involves freezing a sample to better preserve it under the harsh conditions in an electron microscope, and its chief advantage is that it can catch molecules in a more natural state than other methods.

In this case, the scientists hoped to map the structure of GABAB in both inactive and active, GABA-bound states. But when they reviewed data from their experiments, they found they had also caught more detail than they had anticipated. Those new findings include the existence and rough maps of two intermediate states that, Gati said, “we didn’t even know existed.”

But perhaps, more important than the intermediate states themselves, was observing, for the first time, the active form of GABAB, said Vadim Cherezov, a structural biologist at the University of Southern California and the new paper’s other senior author.

To capture the active state, the team added two molecules into the mix with GABAB and took additional cryo-EM images. Adding those molecules – a GABA-like molecule and another, called a positive allosteric modulator or PAM, that fine-tunes GABAB function – stabilized GABAB receptor in its active state.

Being able to see each of those steps along with new details, such as the site where the PAM binds to GABAB, Cherezov said, could help researchers design better drugs to treat neuropsychological disease.

Gati is a Panofsky Fellow at SLAC. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the French Foundation for Medical Research and the U.S. Department of Energy, Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Citation: Hamidreza Shaye, et al., Nature, June 17, 2020 (DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2408-4)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.