Atom or noise? New method helps cryo-EM researchers tell the difference

Cryogenic electron microscopy can in principle make out individual atoms in a molecule, but distinguishing the crisp from the blurry parts of an image can be a challenge. A new mathematical method may help.

Cryogenic electron microscopy, or cryo-EM, has reached the point where researchers could in principle image individual atoms in a 3D reconstruction of a molecule – but just because they could see those details doesn’t always mean they do. Now, researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have proposed a new way to quantify how accurate such reconstructions are and, in the process, how confident they can be in their molecular interpretations. The study was published February 10 in Nature Methods.

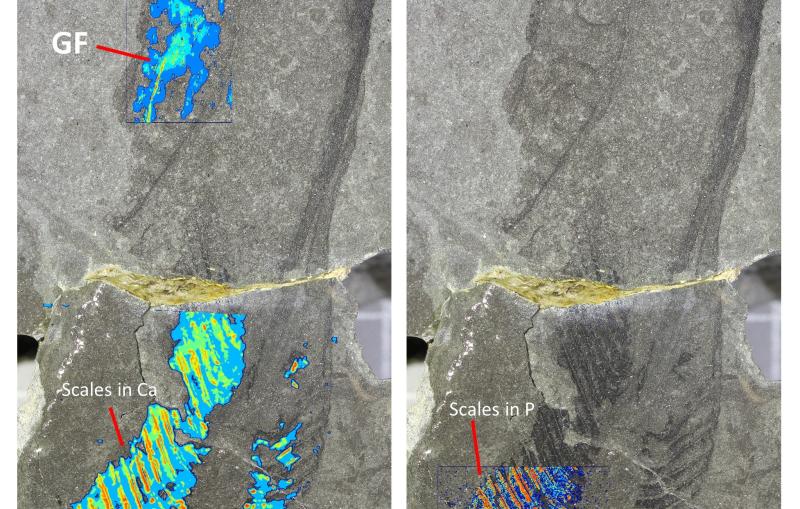

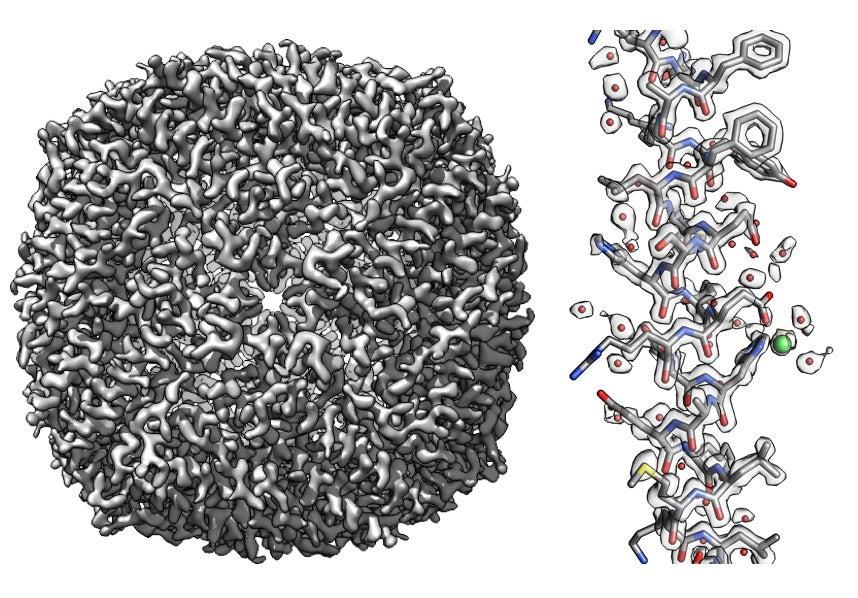

Cryo-EM works by freezing biological molecules which can contain thousands of atoms so they can be imaged under an electron microscope. By aligning and combining many two-dimensional images, researchers can compute three-dimensional maps of an entire molecule, and this technique has been used to study everything from battery failure to the way viruses invade cells. However, an issue that has been hard to solve is how to accurately assess the true level of detail or resolution at every point in such maps and in turn determine what atomic features are truly visible or not.

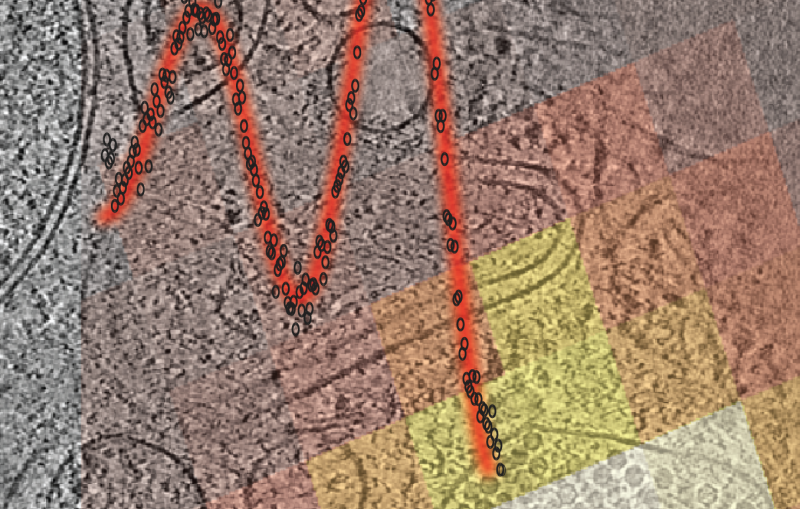

Wah Chiu, a professor at SLAC and Stanford, Grigore Pintilie, a computational scientist in Chiu’s group, and colleagues devised the new measures, known as Q-scores, to address that issue. To compute Q-scores, scientists start by building and adjusting an atomic model until it best matches the corresponding cryo-EM derived 3D map. Then, they compare the map to an idealized version in which each atom is well-resolved, revealing to what degree the map truly resolves the atoms in the atomic model.

The researchers validated their approach on large molecules, including a protein called apoferritin that they studied in the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Facilities. Kaiming Zhang, another research scientist in Chiu’s group, produced 3D maps close to the highest resolution reached to date – up to 1.75 angstrom, less than a fifth of a nanometer. Using such maps, they showed how Q-scores varied in predictable ways based on overall resolution and on which parts of a molecule they were studying. Pintilie and Chiu say they hope Q-scores will help biologists and others using cryo-EM better understand and interpret the 3D maps and resulting atomic models.

The study was performed in collaboration with researchers from Stanford’s Department of Bioengineering. Molecular graphics and analysis were performed using the University of California, San Francisco’s Chimera software package. The project was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Citation: Grigore Pintilie et al., Nature Methods, February 10, 2020 (10.1038/s41592-020-0731-1)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.