so good evening and welcome to the latest installment of the slack public lectures

today we are very pleased to have dr brian lance of stanford university to

come and talk to us about the discovery of gravitational waves by the ligo experiment

dr lance has been intimately involved with this effort

many years ago as an undergraduate at mit he went to work for dr ray weiss one of

the original inventors of the technique used to do the ligo experiment

he went there i guess during the year as an undergraduate and he just got sucked

into it he stayed at mit to do his phd in his phd he did an experiment that

what shall i say for those of you who know about laser measurement set the world record

for the tiniest fraction of a fringe that one could observe in a laser measurement of the kind that

he will describe to you in this lecture well with that kind of a pedigree he then came out here to stanford to the la

to the lab of professor bob byer where he became the leader of the effort involved

in vibrational isolation of these extremely precise detectors that are

used in ligo and so today he'll talk to us about the discovery of gravitational waves and

how what kind of technology you use and how you pull this off so brian thank you very much

great thank you thank you michael is my mic on there we go good well it's a really a great pleasure to

be here um it's great for slack to host these events i see there's quite quite the audience out there including a

couple of faces i recognize in fact i see a couple of folks from mr who's 8th grade science class

they're they're studying gravity right now i'm i'm going to try to keep the explanations tonight as clear as i can

but if you don't understand anything get those guys to explain it to you after the lecture

so as michael said i'm brian lance here to tell you about gravitational waves the the sound

that you get when two black holes collide um i'm speaking on behalf of the entire

ligo scientific collaboration and the virgo collaboration it's about a thousand of my closest friends

the um there we go you can see the folks who

are this is a list of the people in the the ligo scientific collaboration i should say ligo is the laser

interferometer gravitational wave observatory and i'll be telling you about laser interferometers and about

observing gravitational waves tonight so there's a list of sort of

some of the folks in the ligo scientific collaboration uh you can see stanford's over here on the corner

and uh maybe a little extra shout out for the locals

we we run a network of detectors the two u.s detectors for the ligo sites

are at hanford washington and livingston louisiana the virgo collaboration is bringing a

detector online this fall near pisa italy the germans and the scots i mean the

i mean the folks from the uk have a 600 meter detector in northern germany

the japanese are building one underground the australians are have the corner station of a detector in

australia and recently the ligo collaboration has entered a collaborative agreement with the

government of india to build a third liga facility uh in india which should be coming online in 2022 or 2023

on september 14th at these two sites at the hanford site on the livingston site we actually

saw some signals that came from outer space that looked like this

i'll tell you more about this what strain means and exactly how to interpret these signals as we go on

through the talk i just wanted to show you this right at the beginning here's some noise you're not really seeing anything

and then you see this big ripple at hanford and seven milliseconds earlier in fact you saw the same ripple at the

livingston observatory and when you line these two things up what you see is noise here and noise here but a

coincidence signal at those two detectors seven milliseconds apart if you shot if

you shown a light beam directly from hanford from livingston up to hanford to take 10 milliseconds for that beam to get there the fact that

these arrived seven milliseconds apart means that instead of the beam the signal coming in to livingston and then

to hanford it kind of came in at an angle so you can kind of tell where that signal is in space

sort of a ring if you had three detectors instead of doing as a wag recently called it by angulation with three you

could actually do triangulation and figure out where the source was so we're looking forward to the rest of more to

some more of these sites coming online this fall and over the next several years

so what do we think caused those signals let me just show you this we'll talk a

little bit more about it as we go through the through the evening here are two black holes they're sitting in front of a starry

sky and this black hole and this black hole are each about 30 times the mass of the sun

they're so dense that not even light can get out of the gravitational well

they're about uh 400 kilometers about five about 300 miles across

and the edge of this is called the event horizon that's sort of the sort of the

classic edge of that black hole that tells you how big it is light can't get past there and what you're going to see

is that as these two guys go around the starry field behind them is going to get distorted so here they are they're

spinning around you can see the starry night behind them is getting distorted because the light that you're seeing from those stars is

getting distorted as it goes past those two black holes they're spinning in closer and closer

together they're emitting gravitational waves you can see that the stars even out here are getting distorted and in a

moment this is going to slow down and you can watch those two black holes become a single black hole and the whole

background is getting distorted as the waves go out this is a really

pretty picture i'll show you a little more technical version now here again we've got the two black holes

this blue space is sort of a cut through space-time and the colors represent

time slowing down near the black hole we'll start those two things orbiting around each other it's just two objects

just spinning around in space as they're spinning around they're emitting gravitational waves right now we're

about not quite half a second before these two black holes are going to crash into each

other you can see that space is getting distorted time is slowing down if you look into these holes sometimes you can

see a little black ring in the bottom as the as you see the event horizon here

you see time is getting dramatically slowed down the little colors talk about the the direction that space is getting

curved in here's our waveform coming in this is about where we could start seeing that waveform in our detector

in just a moment the wave the thing is going to slow down and now you see that space instead of being just

rather curved near the black holes it's getting really distorted and twisted up

and right there they form a single black hole

and then it ripples to ripples down to a single round black hole in just a fraction of a second that whole simulation was up just over half a

second and now you can see those gravitational waves coming out

all right there's a couple of pretty pictures let me tell you a little bit more about sort of what's going on with gravitational waves now

usually when people think about gravity they think about newton right so here's here's our friend isaac newton and he

wrote down this nice formula the only formula i think that you're going to see tonight about the force of gravity

being proportional to the gravitational constant the mass of the two objects and the distance between them so you've got

some earth you've got some apple in orbit around the earth space is like a big empty stage you've got these two

objects and they're pulling on each other with a gravitational force it does a great job of explaining lots of things

about the orbits of planets things falling onto the ground but it has a couple of problems one of

them is that it implies that there's action at a distance if you have a an object

here your apple and your earth over here and you suddenly were to move your apple

if you believe this equation about force it would tell you that all across the universe

the the force of the gravitation from that apple would change instantaneously and you know that that's just got to be

wrong it's puzzled people for a long time

it was resolved by albert einstein in 1916 when he said that in fact general

relativity is the better way to describe what's happening and instead of space being an empty stage in

which you've got these masses what it says is that there the space is actually like a fabric and that fabric is

distorted by the mass and the distortion in that fabric tells the mass how to move

as wheeler said space-time tells matter how to move and mass tells space-time

how to curve and so you get these curved pieces of space around the around your massive objects

so you've got your sun and your earth here and space is getting distorted a lot by the sun and a little bit by the

earth and their traveling wave and you can describe the distortions in this space

with a traveling wave if things are suddenly moving around i'm not going to try and write those

equations down for you we'll do sort of a simplified version instead right

so if you've got an electron right it's got an electric field if you move the electron you get

distortions in that electric field and if you accelerate your electron back and forth you get traveling electromagnetic

distortions or light and those waves travel out at the speed of light they are light

either visible light or radio waves or gamma rays if you've got a chunk of matter

it's got a gravitational field if you suddenly move the chunk of matter you get distortions in that gravitational

field and those distortions travel out at the speed of light they carry the information about the

gravitational field out to the rest of the universe

let's take another look real quick at our at our cool video here so here you see space getting

curved here you see space getting very curved i want you to to watch some of the colors in here you

can see these these ripples here in the space time as our as our two objects form into a

single black hole if you watch the colors out here what you'll see is these distortions are going to travel out and

you get little funny color distortions as those ripples those perturbations in spacetime travel out at the speed of

light

i could like watch this video all day i do sometimes that's not good so when those waves get to us they're they're

much weaker and the way that they interact with us is if you've got some

pair of black holes they're emitting a gravitational wave when it comes out to out to here if you imagine you've got a

ring of free particles in space as the wave comes through that ring gets distorted into an ellipse oscillates

back and forth as the space time is getting distorted so someone in the bla

in the back row here were to suddenly become a pair of black holes and like collide the waves would come up towards

me and i would get to stretch this way and shrunk this way kind of oscillate back and forth like

this as those waves go past right that's called that's called the stick man doing the stick man

so the way we try to measure that is you put a couple of objects in space

and you measure the distance between them with a laser so here we have a

version of the the ligo interferometer there's a laser that comes in here there's a beam splitter there are these

two long arms and you measure with your laser the distance of this arm and the

distance of that arm and as the wave goes past it's going to distort those distances and you measure that distortion with

your laser now why haven't we done it until recently

it's because space doesn't distort very much right space-time does not like to

get distorted space-time is very stiff so even if you put a lot of energy into stretching space-time you don't stretch

it very much the gravitational waves that i showed you before

took space-time and stretched it by one part in 10 to the 21.

we have the world's best strain meter here we can measure a distortion of one

part in 10 to the 21 with these with these long arms it's not so easy to do and that's why it's taken us so long

right einstein predicted these waves back in 1916. when he did most people figured you'd

never be able to see them there's been a lot of technology advanced since then and we've just now been able to do it

ray weiss who was talking about uh earlier this evening

in 1973 wrote a paper where he showed that using these new laser measurement systems

you should be able to finally build a machine that was good enough to do it

and now what's that more than 40 years later we finally finally managed to do it

um i should say if you take so how big is 10 to the minus 21

right if you take the distance from the earth to the sun it's 150 million kilometers if you distort that distance

by one part in 10 to the 21 it's about the size of an atom

right so that's kind of what we're doing right we're measuring a distance like that it's just we're watching it wiggle just a little bit

right and we can measure that actually with with pretty good signal to noise so

the way we do it as well as one of these laser interferometers i'll show you this show you how this works here's our

here's our laser here's our beam splitter and here are two mirrors you shine a beam out of your laser it

splits the beam splitter goes to the two mirrors comes back and as the two mirrors change the light

coming on to your detector here changes as well the way this works you can imagine this light is an

electromagnetic wave the yellow is the intensity of the electric field it's bouncing off the arm

the blue is the electric field from this arm they come back together at the beam splitter

and they combine here now you see there's every time where there's a plus on the yellow field there's a minus on

the blue field and so they add up to be zero there's no power until you start to distort those arms

and then the field coming out of this port of the beam splitter

the electric fields change and the changes in those electric fields as they line up and go out of alignment

cause power at your detector here what this means is you're measuring in

our case this four kilometer this two and a half mile long this four kilometer arm

with a ruler the ticks on that ruler are a wavelength long right so they're about in our case

about a micron so it makes a really good ruler and

not only that but it's not really good enough right in fact we can what we do is then we measure this intensity very

carefully and we can watch even very slight changes in that intensity so we can actually measure

one i should have done this earlier a trillionth of a change in that wavelength

all right so a little bit of a digression on history turns out this has a funny

there's a funny little connection in history through here so this is the michelson interferometer

built in 1887 by professors michelson and morley and

it looks a lot like what i just showed you there's a light source here they used an oil lamp there's a beam splitter they

one light one of the beams goes through the beam splitter bounces back and forth a whole bunch of times gets to e bounces all the way back to the beam splitter

the other light bounces off here bounces back and forth to e prime back to the beam splitter those two beams recombine

and come to a little siding glass here at f they did this

because they were trying to measure the luminiferous ether in the late 1880s the whole electromagnetic theory was just

getting started and waves travel through something right we all know this at least we think we do

sound travels through air water waves travel through the water light must travel through something

and they called that something the luminiferous ether and these guys were looking for it and they had a very clever experiment what they figured was

that as the earth was moving along through the ether one arm was going straight

into the ether and one was sideways now this arm as you go in you know as the light goes this way the arm's a little

shorter a little longer when the arm goes back this way it's a little shorter there's no net effect for this one but

for this arm as you go along the light's got to go not only to the end of the arm and back it also has to travel forward a

little bit so this light has to travel a little farther than that light and interferometers are really good at

measuring lengths so michelson and morley said hey we should be able to measure

the earth traveling through this luminiferous ether not only that but they did a really

clever thing they took this five by five foot chunk of rock and they were

able to turn it right so they start going this way and then as they run along and so now

my left arm is going to look a little longer they're going to rotate this block now my right arm is a little longer

and now my left arm is a little longer i know i better stop or i'm going to crash into something so they did this really

pretty measurement this particularly appeals to me if you look at the paper what you'll see is

is they say this is version two of the experiment in the first experiment one of the principal difficulties encountered was

that of revolving the apparatus without producing distortion and another was its extreme sensitiveness sensitiveness to vibration

this this is still true um it was so great that it was impossible to see the interference fringes except at brief

periods when working in the city even at two o'clock in the morning and as a graduate student this really appealed to

me they did a clever thing so that chunk of rock is actually sitting in a pool of

mercury it's just like this like science in the old days right you can just turn that thing evidently very nicely

and they didn't see anything they didn't see a darn thing so here's their here's their measurement

right and here's their prediction for what they should see actually divide the prediction by eight to fit on the

same plot and they're like that's weird because you know if you're if your interferometer is stationary it's clear

that the arm should be the same length but if your interferometer is moving and the arms should seem like they're a

different length as you go through the luminiferous ether and this caused quite a bit of

discussion in the physics community at this time and and no one could explain what was

going on until not until albert einstein came along in 1905 we see with his special theory of relativity and said

look the speed of light is a constant doesn't matter whether you're you're sitting still or you're moving along at a

constant velocity the speed of light is the same right there is no lumen at first ether that's why you couldn't

measure it the special theory of relativity then evolved into the general theory of

relativity which predicted gravitational waves which we measured 100 years later

with a michaelson interferometer i just think that's cool all right so here we come back to our

interferometer it's hard to measure

these distortions in space time because space doesn't like to get stretched what are some tricks we do to make this

to make this machine actually good enough to do it we're sort of three classes of tricks first you make the

arms really long our arms are four kilometers long two and a half miles long that's how much

that's how much vacuum system we could afford that's how long we made it the longer you make the arms the more

absolute length change you get for a particular strain so the longer they are the easier it is to measure your strain

second thing you do here's a little more detailed version of the interferometer the second thing you do is you measure

the distance change in those arms very accurately so

somehow you have to measure this length and measure this length very precisely i'll tell you just a couple of tricks

that we do to make this happen first like michelson and morley did we bounce

the light back and forth in this four kilometer long arm about 300 times so instead of being sort

of like four kilometers it's really like what 1.2 000 kilometers so it's much the

effective length is much much longer

i'll just point out right now there's 100 kilowatts of optical power in these arms by the time we're done it's going

to be almost a megawatt of power stored in these arms why do you need that much power so when

the light comes back out of these arms it comes to the beam splitter and your ability to measure the relative change

of those two arms comes down to the counting statistics the counting statistics of the photons at that beam

splitter if that's true what you want is you want a lot of photons so another trick we do is we

have a really big laser um we have the best science well

various ways to define best for my way we have the best laser in the world so we should this thing can put out about

125 watts of very very very clean laser light at one micron it's a gift in kind

by the german government here you can see a couple of guys that lasers and from hanover working working on that laser

you can put out about 125 watts when it's working um but that's not enough right we need more

power than that so there's another trick we play and i'm just going to kind of tell you what it is rather than trying to describe it very carefully

in the picture you saw the interferometer before what you saw is that when there's no gravitational wave there was almost no light coming onto

the detector down here almost all of the light was going back towards the laser

so what we do is we build an optical cavity when we sort of in a very california sort of way we recycle that

light instead of just letting it fall out of the infrared we turn around we push it back in and we store this light

at our beam splitter so with our last one we had 20 watts going into the interferometer we had 800 watts

in our power recycling cavity sorry i love acronyms in our power recycling cavity at the beam splitter and that

gave us enough optical power that you could really accurately measure where

you were on that optical fringe the third thing we do this is my

favorite you keep the mirrors from moving right the interferometer tells you how far

apart the mirrors are so you want to measure that very accurately and you want to keep the mirrors from moving right so the only thing that changes the

distance is the gravitational wave actually stretching the space so how do we keep these mirrors from

moving here's a here's a picture of the vacuum system

that holds all these things it's a big ultra high vacuum that mirror that i showed you before is in this vacuum chamber right here and if

you zoom in and sort of cut away the walls what you see is a contraption that looks like this for scale

these posts are about eight feet tall the top of this chamber which has been taken off about 18 feet off the ground

here's our mirror we start measuring above 10 hertz

so low frequencies kind of these kind of distortions we just try to control those out we only start looking for

fluctuations in space faster than 10 cycles a second and we look for it at these mirrors at

10 cycles a second at 10 hertz this mirror has to be moving a billion times

less than the ground does if we want if we want to hit our if we

want to hit our requirements which we're doing a pretty good job of we do that with seven stages four stages of

pendulum two stages of seismic isolation system and an external stage of laminar flow

hydraulics i'm just gonna tell you about the hydraulics for just a second there are lots of things that make

running an interferometer like this difficult one of them is that you have to keep the distance of those arms

more or less fixed it can't move by more than about 10 to the minus 13 meters or the light comes out and the

whole interferometer stops working so to hold it at its operating point you have to control the rms length of those arms

now we all know about the tides the moon goes overhead the water goes up and down what most people don't realize is that

in fact the ground moves up and down to about plus minus six inches and as that tidal bulge goes past the earth

the ground around that bulge gets stretched a little bit and these four kilometer arms actually change their

length by plus minus 120 microns twice a day now the distance between the mirrors has

to be fixed and the ground is sliding back and forth underneath them so you've got these big hydraulic systems that

push the mirror against the ground as the as the moon is distorting the ground so

you can keep your interferometer working

the guy who told me about building hydraulics like this these super quiet laminar flow hydraulics is a professor dan de bray

who's sitting right here so he's kind of the the smart guy in our lab if you have any questions about seismic talk to dan he knows all about

it all right so back inside so here are here our mirrors here's sort of a cad drawing of the

mirror the mirror itself is a piece of glass about 34 centimeters in diameter about 20 centimeters thick weighs about

40 kilograms about 90 pounds um and it's suspended as a four-stage

pendulum and i brought a demo so

why would you suspend so here's the here's the advanced ligo optic

um why would you suspend this on a pendulum if you take your suspension point

and you move it at low frequencies of course your optic follows kind of follows along

you can use this to put your optic where you need it to be for the interferometer to work if you move your suspension point at the

resonance of the optic the optic moves a lot more than your suspension point and this is bad so we have all kind of

controls around our optic to damp out those those fundamental modes the good thing about a suspension

is that if you move the suspension point at high frequencies what you see is you get a lot of attenuation

between the suspension point and the optic works both horizontally and vertically

and of course if some is good then more is better right

see if i can do this so with a two-stage pendulum

you should be able to move the top really kind of a lot and you can see now my suspension point

is moving a tremendous amount and as long as i don't hit the resonance the optic just can't keep up so you get

a lot of isolation between this top of the optic and the mirror itself

so for advanced ligo it's a factor of about 10 million at 10 hertz

we have the world's best optical coatings and if we do it right the motion at 10 hertz for that optic is actually driven

by its thermally driven excitations so the ground isn't actually the driving anymore it's the it's a thermal

fluctuations of that optic and one of the cool things that we do to

make that happen is that in fact not only is this thing a piece of glass but the one above it is a piece of glass

and they're bonded together they're little ears that we join onto here

and then onto the ears we have glass fibers and this whole thing is welded together into a single when you're done

it's a single piece of glass if you whacked that thing you get in a lot of trouble but if you whacked it it rings for about 10 million

cycles before it finally calms down

here's a picture of the scale of it this is a betsy she's our lead suspensions expert at the hanford

site standing next to one of the engineering prototypes here's the a mock a mock-up of the mirror you can see how

big this thing is right so here's the top of that four-stage pendulum attached to the optics table

if you use real if you look at the real optics what you see is something like this they're much they're much prettier but you can't actually see who's working

on them so that suspension actually gets attached to the to the seismic isolation

table this this is the table here suspension bolts up on the on the bottom

at one hertz this table is a thousand times quieter than the ground at one hertz and this is

really useful because instance at livingston at the livingston

site there's a train that's right near one of the end stations right so the end mirror of one of the arms there's a

train next to it and they load logs up onto the train they drive it across this rattly bridge and it used to be that

twice a day the whole interferometer would fall out of its working point you couldn't run it while the train was going past

now smooth the silk because the the the table here keeps the thing quiet

at low frequency so it's easy to control you can see it's got springs here and masses you get the same kind of pendulum

isolation that you do with your suspension but also it's covered with high performance sensors and actuators

and control systems and so at very low frequencies we can use our active control systems to hold it quiet

again dan told me how to do that here's a picture of it being installed

at the observatory and a couple of pictures of the prototypes down in my lab down down on

campus that a two-stage platform here the optics table is on top this is wen chang hua here's dan clark next to a

later version where it's got all kind of high performance sensors set around on it these are for control the user to

measure how well the thing does as i said at one hertz we can make it a thousand times quieter than the ground

does okay so now we've done sort of three things

we've got really long arms we can measure the distance between the mirrors in

those arms very accurately and we're holding the mirrors really quiet

and what we're looking for is for something to change the length of the arms

and that for that something to not be us right so

this is a spectra it's called a spectrogram of the of the two events

you get about half a second of data and what you can see right here

is the event this is going to be a sound i'm going to play this in just a second let me tell you what's going to happen for the first sort of half a second

there's going to be a rumbling and that's what the interferometer sounds like when there's no signals just sort of the residual

noise in the instrument and then the signal comes in you can see it's about 200 milliseconds

and here we have 30 hertz and you can see it's very loud starting at 30 hertz and running up to about 150

hertz over you know not quite 200 milliseconds so here's what it sounds like i hope

with just the noise so that's no signal let's see if i can do that again

now we're going to play it again i'll play it twice with the signal and then we're going to shift it up to

kind of put it a little more in the audio band same signal just frequency shift it up a couple hundred hertz play

it twice the higher frequency and then we'll repeat that so this is what it sounds like if you take the output of

our detector and you play it on a pair of speakers right so they told me i had to make the title something about the

sound of black holes colliding this is it

the little whoop whoop is something we've been looking for for a long time now we call that the the

chirp and when you when you take a look at the signal as a function of time here you

can see it at hanford in louisiana again it's sort of half a second long the strain the maximum strain is about one

part in 10 to the 21 and this is the hanford and the louisiana

detectors lined up here we have the best fit numerical relativity model of the event

and when you take the actual signal and you subtract the best numerical fit

for the signal this is what you get left this is the noise so we call this our signal and this is our noise and here's

a spectrogram of that this signal is filtered out so you don't really see anything below about 40 hertz

if you do a better model for what that signal looks like down to low frequencies you get a signal that looks like this

and i should really at this point give a shout out to all the people doing numerical relativity

ten years ago you couldn't actually model a single orbit of two black holes going around

each other on the computers you just couldn't do it i was at a talk once and they someone said something like

the coordinate system for the calculation fell into the event horizon

you know like i'm not even sure i understand what that means right but it's as bob wagner down on campus said he's

like well wasn't a very good choice of a coordinate system now was it

anyway you can see they've gotten much much better and it's critical to actually being able to understand what

happened so from this wave form we think the two

black holes were 29 and 36 solar masses and my wife was harassing me earlier this

week saying the biggest like the question that people always ask her is how do you know

what the black hole masses were so let me just give you a comparison

this is the signal that is the best fit to the signal that we saw

about about 200 milliseconds here's a four second version of the signal that we were

expecting this is two neutron stars neutron stars are about 1.4 solar masses

um you and it's here it's about 50 hertz here it's about 900 hertz and you can't even see

what's going on in here because there's so many cycles if you zoom in on the end

then you can do a better job of comparing these two signals and what you see so here for the same 200 milliseconds at

the end of the signal this is what a black hole in spiral looks like this is what a neutron star in spiral looks like

they look about i mean they look qualitatively very similar they the frequency

is getting faster the amplitude is getting bigger and then it falls off and that's true for both of these

but the actual frequencies are very different right and it's the change in frequencies

it lets you measure the mass another another thing you could do is you can compare

when these two signals are about 65 hertz right at rest sort of right here so this is what the neutron stars look

like the lighter masses at around 65 hertz you go forward five cycles looks

about the same go backward five cycles looks about the same if you squint you can see that the amplitude

here in the amplitude here has changed a little bit you know here if you start at 65 hertz

and you go forward five cycles the whole event's over you go back in time five cycles and

you're not even in the detector band anymore so by looking at the rate of change of that signal you can figure out

what the masses are we think those two masters were 29 and

36 solar masses and they've spun into a single black hole which was 62 solar masses

and the eighth graders in the room are probably doing some math right now what they see is that this is 65

and this is 62 and that as these two black holes crashed into each other

three solar masses of mass went away so einstein tells us that e equals m c

squared m is three times the mass of the sun

this thing emitted three solar masses of energy in a few milliseconds that means

there was a much power coming out of this thing the amount of power coming out of this was 50 times

more than all of the power of all of the light coming off of all of the stars in the

visible universe i can't even get my head around that right it's just ridiculous right it's a tremendous amount of energy and yet when

it got to us you could barely see it right i mean it's just i mean the signal noise is pretty good but strain of 10-21

not very much um

we were we were lucky that we saw it in fact um how lucky were we

the first observing run for advance lago was supposed to start on september friday september 18th

for about a month before then we've been doing an engineering run kind of getting everything ready for the first run getting it all tuned up making sure it

ran for a long time without trouble making sure all the calibrations were right in the middle of the night on

monday people are like okay it's time to go home switch it to on

they leave the site it's like two in the morning at hanford about 45 minutes later after everyone's

left signal comes in like well i guess we're starting

observing one a little early aren't we don't touch it don't touch the machine we've got to get enough statistics that

we can tell if this is a real or not all right so i'm coming near the end of

my time um we spent a long time getting to the point where we finally

measured the first gravitational wave and so you might say that we've gotten

to the end of our quest but i'd like to argue it's not the end

it's actually the beginning right it's not the end of the quest to find gravitational waves

it's the beginning of a new kind of astronomy you know people been looking up at the stars for forever since there were people like

you walk outside tonight if it's not too cloudy you can walk up and see a beautiful night sky

the neat thing about looking at the stars in the modern era is that when you look in the visible

light you see images like this of our milky way but every time you look up at the stars

with a new instrument what you see is something different right

here's what the here's what our milky way looks like if you look at it with the fermi telescope run

here out of out of slack um this is what the sky looks like in gamma

rays and you can see that there's the milky way in here but it's not

it is not the same the first gamma-ray telescope that went up they put it up to watch

the russians to make sure they weren't setting off nuclear weapons and what they saw was that there were explosions

in gamma rays coming from the other direction and they they thought maybe the russians are setting off

nuclear weapons on the other side of the moon right which is pretty crazy but in fact what's

actually happening is probably even more crazy and we're not exactly sure what it was but maybe i'll i'll come back to

that in a minute here's what the sky looks like if you look in the in the infrared this is a

satellite uh image from kobe um from the fear ass machine here you can see now the center of the galaxy is

very bright here it's very dim because it's it's obscured by dust dust in our galaxy here you can see it

quite clearly if you look at that same that same telescope same instrument same

satellite and instead of looking at the infrared you look at the microwaves and you pull out the galaxy and you look at

the stuff that's behind the galaxy what you see are fluctuations in the microwave field that are left over from

the big bang that's what kobe that's what kobe tells you these are fluctuations in the microwave background

left over from the big bang that tells us how the universe started

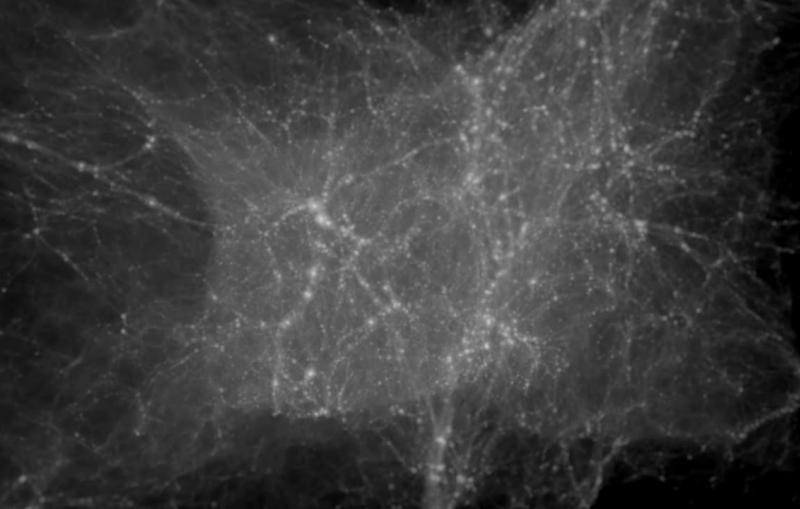

and now we have another way of looking at the at the sky and it looks kind of like that

actually to be fair this thing was only on for 200 milliseconds so i should turn the star off right now but i just i just can't

bear to but we think that now with this new instrument we're going to be able to

learn to learn a lot more with gravitational waves you can look at anything that's got a lot of mass and

it's shaking around this might be the centers of supernovas when the center of that star collapses

driving one of the most energetic events in the universe it might be the neutron star that's

formed after this supernova the neutron star here this is the crab nebula

um in 1054 this was a supernova the Chinese could see it in the daytime and wrote about it now there's a neutron

star in the middle it's sort of the density of nuclear matter and it's spinning around around 60 hertz if it's

got a little wart on it that little wart spinning around 60 times a second and pretty soon

the gravitational waves from that thing maybe we'll be able to see them

be very interesting to tell you maybe what the neutron star is actually really like

maybe when you have two neutron stars that crash into each other the kind of thing that ligo started out

looking for here's our little neutron star in spiral from earlier

what you see when these two neutron stars crash into each other these are actually matter right they're not like

curvature of space-time black hole things they're actually stuff and if when they crash into each other

with their dense matter and their magnetic fields what you'll probably get is a huge burst of gamma rays

we think that's one of the sources of gamma-ray bursts if we see

a gravitational wave signal like this followed by a by a gamma ray burst on the for instance the fermi telescope a

few milliseconds later we'll know what gamma ray bursts come from be very exciting

not only can we combine the gravitational waves with other kind of instruments but there are also a bunch of new gravitational wave instruments

coming online ligo can see gravitational waves at around 100 hertz

100 cycles a second but there's some other instruments that people are working on there's one in outer space called e-lisa

instead of being four kilometers long those arms could be a few million kilometers long and look

for gravitational waves at lower frequencies down here where you might have black holes in the center of the

galaxies crashing into each other there's also a group called nanograv people i stole this slide from looking

at radio pulsars around the galaxy and looking for distances from us to the radio pulsars to change at sort of

periods of weeks or months indicating that very low frequency gravitational waves have gone by from for instance

again the black holes in the center of galaxies crashing into each other there's also people looking at the

microwave background that thing that i showed you before with kobe looking for fluctuations in that

microwave background caused by gravitational waves from the beginning of the universe

so i'll argue that it's not the end it's actually

the beginning of a new kind of astronomy and i'll also argue that although it's

the end of my talk it is the beginning of the time for you all to ask questions

i'm really glad you guys came out thank you very much

now i think okay so brian

thank you very much um we now have time for questions and let me remind you of how this works

um there are some of my colleagues standing in the aisles here with microphones raise your hand and be

recognized wait until you get the microphone to ask the questions otherwise we're recording this the

question will not be in the recording and sir why don't you take the first question

you have this wonderful instrument has it measured anything else since

good good question um the this event was from data from the first

third of the first observing run um the second two thirds of that observing

run we're now processing the data and those event that will release that

um soon in the next couple of weeks maybe month or so and then then we'll know still still looking um

then we're going to start the second observing run this fall and the predictions for that are

anywhere from a few events to maybe 10 if we're super lucky we'll have

to you know keep keep your fingers crossed for us when that when that run starts but check check the news in a couple of

weeks and see if the data from the rest of the first observing run has come out yet

anyone please

we hope of matching your uh measurements of gravitational waves with the gamma

burst uh related to the same event and the second trouble understanding what you're saying um

so that collision of this two black holes probably will also produce some burst of gamma

rays maybe any hope of matching like time wise

and confirming that that was uh and maybe finding the right place is there any kind of coincident thing that we saw

in with other observatories that went along with this gravitational wave um for like for the neutron stars you

should definitely see something like that because there's real matter and it's crashing into each other at some

reasonable fraction of the speed of light you would definitely expect to see gamma rays

for the black holes if if the black holes have kind of sucked up all of the normal matter

around them you wouldn't expect to see any signals

in the visible because there's just there's just space time getting distorted if there's still some matter around then

you might see something and in fact the fermi collaboration released a paper

recently saying that they had there might have been something in the gamma rays about 400 milliseconds

after the event it it wasn't strong enough to be significant except for the coincidence

time and it was kind of right at the edge of the earth so it subject to confusion but

you know it's one of these things that you can't you can't dismiss it so i'll give you a

maybe on that one and also that would be a way to compare the speed of gravitational wave it would

be yeah it would be a way to to see if they're actually traveling pretty close to the speed of light which would be

very interesting to see i mean we expect that they travel the speed of light but being an experimentalist i'd like to

measure it yeah

a question here uh that last question kind of was my first question so i guess i'll move on

um i'm kind of curious going back to michaelson morley um they didn't have a laser

right how did they pull that off they were good they had an oil lamp

yeah yeah they had a so the

there's a thing called the coherence length which tells you when light comes off of something how far along can you

go on that light and the wavelengths to still be sort of reasonably well related to each other

for ligo it's like forever for these guys it's very very short and they had to align the absolute length of

their five their 11 meter long arms to a to just a few i don't know just a

few wavelengths um to get their oil lamp fringes to line back up

they were very patient

i've been texting my grandson notes from this lecture and his question is

can anything surf a gravitational wave

i wish wouldn't that be cool amplitude's pretty small um and people

have talked a long time about trying to somehow harvest the energy of of the gravitational wave to some good effect

and so far we haven't done it yet but um you know he's still young enough he

might be able to in a few years he might be able to tell us the answer that'd be good

okay please thank you how long did it take to build

the entire structure yeah so we started so initial ligo got

its funding in um

the mid 90s built the initial ligo detector

uh kind of the the construction of that happened in the late 90s ran that for a number of years

didn't ever see any signals with that i started doing research on the advanced

ligo detector when i got here to stanford in 98 1998

started working with dan and others to figure out how to build those seismic isolation systems and doing sort of the

research for those we started in

installing in like 2009 i think about

um and it's the machine was down for several years as we were bolting stuff into it so it's been a while coming

on yeah okay way in the back

yeah do gravity waves distort other things besides

length such as i'm thinking time and if so do you have to compensate for that when

you do your measurements right if you remember the

animation at the beginning there were some funny color distortions near the black holes as they were

colliding which meant that there was some time distortion the color was the time but there was some time distortion

near those black holes by the time the waves get to us they're weak enough

that you can just you can describe the event as merely a

distortion of space you don't need to involve a time distortion as well um

i'll i'll i'll stop there i'm not a gr guys i'll just i'll just stop at that

it's hard to think about these things okay my question is i understand that

you're measuring about 10 to the minus 21 meters and you mentioned earlier that you were able to measure about one trillionth of

a wavelength but the wavelength is only about a micrometer so that doesn't get you anywhere near 10

to the minus 21. so how do you get there yeah that's right so we're measuring a strain of 10 to the minus 21.

the length is 4 kilometers so the distance we're measuring is 4 000 times 10 to the minus 21 it's

about 4 10 to the minus 18 meters is the length that we're measuring and that's how you that's

where that extra factor comes from right so that's how we're getting the

you know the factor of 10 to the minus 12 of 10 to the minus 6 gives you 10 minus 18 meters and the

signal is about 4 to the -18 meters

yeah let's see i wonder if you had any theoretical estimate for how often you

have colliding black holes like how lucky were you you have to wait another century for another one like this i should have said

this when i was giving the talk in the history of astronomy there's only

ever been one collision of black holes ever measured that's the one that we did

right so far right there might have been a second one in the first set of data that's kind of marginal anyway there's

more data coming out soon based on

16 days of data and one event you can make some statistics about how

often these things happen and any statistics teacher would tell you that it's kind of dodgy

we think it's between two and 400 black hole binary mergers

per year per cubic gigaparsec from

three billion electric cubic three billion light years um we hope soon to get a better estimate on that

when we and and it's funny it's um a guy named franz pretorius who's actually the guy who got that black hole

merger calculation to work was out at stanford a couple of months ago giving a talk and he's like

how come everyone's like like dissing on these black holes i love black holes like why why weren't you

thinking about them and there were a few people who thought we'd see them first kip thorne for instance was one of the guys who said you're probably going to

see black holes first because the signals are so big but the problem is we had no idea we had no idea what the

event rate was there are several papers that predicted it correctly and a whole slew of papers that predicted it

incorrectly so um we're actually very pleased to actually have some data now

yeah is somebody over here

i was wondering if uh all the energy that was released by the two black holes

colliding was in the form of gravitational waves you said the mass shrank by about three

solar three solar masses that we think so yeah we think that it's all came out as gravitational waves

i mean that's what the that's what the numerical relativity models show us

if you believe general relativity is right then the answer is yes

we'll see

so could the gravitational waves if uh like if something in space is close

enough to the black holes colliding could it cause like a physical change in the object like pushing it off orbit

or like breaking off a chunk of it yeah it would be bad if you were too close to those gravitational

to those two black holes spinning into each other um what you would see most likely if you got really close

is you wouldn't see the wave at first what you would

just see is the the force of gravity being really strong on you which would kind of

cause you know how the the moon causes tides on the earth and

it stretches the earth just a little bit it would be like that except it would be a lot worse it would like stretch you

right out into a pencil um and that'd be that'd be it for you and you kind of wobble around as the as the masses

went past yeah it'd be ugly

the age-old question have you figured out whether gravity is a wave or a

particle or both so in this regime we're treating it purely

as a wave you would in a place like slack which is filled

with particle theorists right particle physicist you better say something about the graviton

the mass of the graviton is very small it would be surprising if we could measure if we could build

something that could individually measure gravitons there's a very interesting paper though i'm

looking for a whiteboard if you go to papers.ligo.org

papers.ligo.org you can get the main event

the the paper describing the event there for free you can download it for free there's also a whole series of companion

papers and one of them talks about the what you can learn about general

relativity from this event and although you can't see individual gravitons

what you might think is that if gravitons had a mass that they might get

smeared out they wouldn't be traveling at quite the speed of light and if they're not traveling at quite

the speed of light then maybe the more energetic ones would travel at a different rate than the less

energetic ones and that that waveform which has some low energy ones at the beginning and some high energy ones at

the end would get distorted as it traveled 1.3 billion light years through

space and from that you can set some limits

on sort of the behavior of the graviton so far we don't see anything interesting

but you can it's an interesting question to ask and i think as we get more statistics and look at things that are

farther from the earth maybe we can start to accumulate some more data about sort of the

the behavior of the graviton be interesting to see

what about the velocity of propagation of gravitational waves

is it equal to the velocity of light or uh oh the speed of the gravitational waves yeah the same the speed of light we

think so um we we don't have a good independent measure of that because all we have is

these you know sort of eight cycles and 200 milliseconds that's what we got um we

you can predict the generation of that signal very accurately with the numerical relativity model

even when the gravitational fields are very intense or can see in here space is quite distorted and we can

still do a good job of measuring that which means that numerical relativity and general

relativity seems to be holding up to the tests and if that's true

the gravitational waves should be traveling at the speed of light now that's a kind of let's a lot of

where fours and what fours and maybe this and maybe that we don't have any evidence

but i will say this we don't have any evidence that they're not traveling at the speed of light there's a question earlier if there's some other thing

like like a supernova that emitted neutrinos and and light then you could compare the time that the light gets to

you and the time that the gravitational wave gets to you and get a better measurement we haven't been able to do that yet but it would be interesting to

see that thank you do you have any thoughts as to whether

the experiment that you have there can shed some light on different theories of

quantum gravity is sensitive enough enough to discriminate between

different theories i don't think so um

again trying to think of

i've seen any discussions about gravity with you know with

with sort of you know with interesting potentials yukawa potentials and that sort of thing that you could dismiss with this and so far

i i think that would be a tough one that'd be tough or maybe you want to chime in on this

yeah i'd like to determine there there have been some papers on the question of how this

these 30 solar mass black holes got that close together so that they could actually make this

event happen and some of the theories of that have to do with quantum gravity in the early

universe so that's a way at it um other people think that well there

are lots of binary stars and some of them are big and this is just something that would naturally happen and it's hard to get

data on this how many black holes do you create that are a certain distance apart

and in what kind of environment so i think astrophysicists will be arguing about this for a long time

but potentially this is a source of information if we could only ever figure it out

okay let's take three more questions and then we'll end so uh please who is that

there's one over here

um hi um so i know in i think 2014 or

15 i think there was a false detection of gravitational waves by ligo that had to deal with like these e modes and b

modes and it was i think talking about primordial gravitational waves and that wasn't ligo that was um

the bicep experiment oh it's from the biceps okay also here at stanford yes yeah the primordial stuff is not like it

we can't we can't see down to those kind of frequencies so do since okay since if those were a

false reading and those were i think connecting to the theory of the big bang since we've detected these gravitational

waves from these black holes does that mean we should does that mean that the search for these primordial

gravitational waves is going to continue still or is this uh good enough to

i guess confirm no i think that the i mean the questions that we're trying to answer with

black holes and neutron stars and sort of or contemporary astrophysics in the last

few billion years um i think are quite complementary to the early universe

questions the things that bicep and planck and the the primordial

uh black gravitational wave people are looking for um

so the imprint of gravitational waves on the on the microwave background tell us much more about sort of things that were going on right

right at the big bang and i think that both are interesting and they're and they're different um if

anything hopefully the sort of the excitement that comes from this will you know drive the field forward a

little bit that's what i would that's what i would hope

i'm not supposed to begin you twice described

time space or space time excuse me as stiff is that more correct than saying that

these forces are weak or was an arbitrary choice it's a similar way of saying the same

thing right i mean it's just except that when you talk about

two objects close to each other and you say well you know you look at the electron and the proton and they've got

some electrical force and they've got some gravitational force right you don't need a wave to describe

the gravitational force between them you can just say that you know one you know the electrical electromagnetic force is

much much bigger than the gravitational force but by the time you get out to where you're looking at you know several

wavelengths away the sort of classical way of describing gravity is just a force you can't really

use it anymore and so you need you need sort of einstein's way of describing space time and there you sort of have to

rely on things like saying space time is very stiff right because it talks about how the waves are

propagating but yeah in the end it should in the end it better come out to the same thing

right yes okay last question who has it

there's one here

before we close is it possible to hear the sound of black holes colliding one more time one more time

she was hoping to hear the sound one more time let's see

okay there it is

okay thank you all for coming we'll go out in the lobby and brian will

be out there