michael peskin: Okay let's go ahead um i'd like to welcome you all to the latest installment of the slack public lectures at home, as it were.

michael peskin: we're sorry that you can't come to SLAC and join us in the. michael peskin: Panofsky Auditorium, but we hope that, as the vaccines are distributed and Bay Area life comes back to normal will do that soon, but for the moment, we hope to present a very interesting lecture in this format and will continue to do that, over the next few months.

michael peskin: So, today, the speaker is Caterina Vernieri she's a Panofsky fellow at SLAC working with the ATLAS experiment at the CERN large hadron collider the LHC.

michael peskin: Caterina got her PhD in Italy in Pisa under the leaning tower, as it were.

michael peskin: Working on an experiment at Fermilab then she moved to.

michael peskin: what's called the cms experiment, one of the large experiments at the large hadron collider um she moved to fermilab for a postdoc and during that time.

michael peskin: She really did some very interesting work, I remember when she came here as a young postdoc to SLAC and told us how to find higgs boson ones that.

michael peskin: were ejected, from the lhc collisions at very large momentum a completely new method and when when you can't beat them you join them or hire them at least.

michael peskin: So she's now here as a postdoctoral fellow at SLAC and working on the next stage of how we will explore the higgs boson at the LHC and so without further ado Caterina please go ahead.

Caterina Vernieri: Thank you Michael for the kind introduction, so alright, so today indeed i'm going to tell you about my favorite

Caterina Vernieri: particle the higgs boson and how we capture it and before I get into the lecture I actually want to tell you a little bit about

Caterina Vernieri: how I decided to become a particle physicist. So I was born and raised in this little town on the Amalfi Coast in the south of Italy, and when I was a kid there was one thing that I loved was watching this

Caterina Vernieri: Italian a popular science TV show called Super Quark in hindsight was a big clue about my future career. Anyway, I was fascinated about those stories I would

Caterina Vernieri: Watch in this program about scientists and how Caterina Vernieri: They would tackle the big mysteries of nature, with their research, so I decided early on, I wanted to be a scientist but I didn't know which type of scientist and more important, how to become one.

Caterina Vernieri: Until the end of the high school I realized that what I wanted to become was a physicist because physicists are those scientists that they're actually trained to

Caterina Vernieri: investigate the fundamental laws of nature, as well as to the device experiments to investigate those theories and I moved Pisa and

Caterina Vernieri: I decided ... I didn't have really a clear path on what to do next until I got to visit, for the first time a particle detector, a particle experiment.

Caterina Vernieri: And I was struck by these objects, it was a giant object, with all the cables coming out of it, very complex, and several scientists were working together in order to

Caterina Vernieri: operate it and understand the data coming out of it, so I decided, I wanted to be part of that and I then

Caterina Vernieri: graduated in Pisa in particle physics, and I left the day after my graduation and I started moving West, first, I went to Geneva, then to Chicago.

Caterina Vernieri: And finally landed here at SLAC a couple years ago to work on a very exciting project that i'm going to show you by the end of the lecture.

Caterina Vernieri: And this is one of my favorite picture of myself, standing next to a particle detector experiment, you can appreciate the amount of cables coming out of it and, later, I will show you what actually, this is and hopefully you will agree with me that this is pretty cool project.

Caterina Vernieri: Alright, so the plan for today is that I will start by giving you a general introduction to particle physics what it studies.

Caterina Vernieri: And what kind of mysteries tries to solve and then I'll tell you more about the Higgs boson and what it is, why it's so special and what we don't know yet about it and

Caterina Vernieri: Then i'll give you a little bit of an overview about how we look for higgs bosons and how we measure them and then I'll show you the next generation of the camera for the LHC that we are building at SLAC.

Caterina Vernieri: Ok, matter, if I tell you that matter is made of molecules and atoms. That it's all we are used to when we think about the ordinary matter, we know that atoms are the elementary unit that forms an element in the periodic table of.

Caterina Vernieri: All the elements specify them all and all their properties and all those that have been found in nature, and we would think that this is it.

Caterina Vernieri: But actually that's just the beginning of the story, because atoms have more complex structures and are not indivisible.

Caterina Vernieri: But if we were to investigate them on the shortest scale, then what we would appreciate if they have an inner structure, they are made of a nucleus, and one or more electrons are orbiting around them

Caterina Vernieri: and at much shorter scale, the nucleus is not fundamental either but it's made of particles: protons and neutrons.

Caterina Vernieri: and protons themselves as well as neutrons are made, of even smaller particles: the quarks so the matter at shorter scale

Caterina Vernieri: are actually made more simple particles the quarks and electrons and those are the simplest the particles we have detected so far with no inner structure.

Caterina Vernieri: And to give you an idea of how shorter of a scale we're talking about I wanted to make these comparison, so I want you to imagine the atom to be as big as the distance between the moon and the earth.

Caterina Vernieri: Then the nucleus would be equivalent roughly to the extension of Menlo Park, and the person would be

Caterina Vernieri: as big as SLAC. And then in comparison a human being would be the size of the smallest particle we're talking about so that's the short of as short of a distance

Caterina Vernieri: we are expecting nature. This is when particle physics kicks in. It focuses on the elementary constituents of matter and their fundamental interactions.

Caterina Vernieri: Now. Caterina Vernieri: To the best of our knowledge, our way of

Caterina Vernieri: describing fundamentally reality is through fields. So fields are those entities that oscillates and propagate through space, which is a very abstract concept.

Caterina Vernieri: So I want to give you an analogy that hopefully, will help you build in some intuition about what the field is. So imagine you have an antenna propagating a radio wave to your device.

Caterina Vernieri: What's happening here is that we have an oscillating electrical current that is generating a signal, an electromagnetic wave that is propagating through space.

Caterina Vernieri: And it generates an electric signal in your device, and that is transformed by the receiver into the music that we listen to.

Caterina Vernieri: So what quantum mechanics tell us is that these waves, these radio waves are actually made of particles, photons to be precise, and the frequency of isolations of those particles

Caterina Vernieri: sorry, the frequency of oscillations of the wave, it is then related to the energy of those particles, the photons.

Caterina Vernieri: So what quantum mechanics is telling us is that the particles are essentially oscillations, so I want you to think of particles as oscillations of the field, local vibrations of the field.

Caterina Vernieri: And this is very difficult to explain in classical term, it is the essence of quantum mechanics.

Caterina Vernieri: But for what, the sake of this lecture, what I want you to remember it's that particles are essentially oscillation of the field.

Caterina Vernieri: and are associated to those. In nature, we have discovered a number of those fields and

Caterina Vernieri: All of them behave similarly, when we turn off the source of the field, the field is zero, with one exception and that's the higgs field and we'll talk more about that later.

Caterina Vernieri: And we have a number of fields in nature and why we have this many it's actually still a mystery that particle physicists also trying to address.

Caterina Vernieri: Then. Caterina Vernieri: The standard model of particle physics is a theoretical framework that we use in order to

Caterina Vernieri: summarize our current understanding of all the elementary particles in the fundamental forces that we have discovered so far.

Caterina Vernieri: And it's essentially, you can think of the standard model as the periodic table of the elementary constituent of matter.

Caterina Vernieri: So we have several types of particles and they are grouped into families, we have the leptons and the quarks that are essentially forming the building blocks of ordinary matter.

Caterina Vernieri: And they do not have any detected structure and they are associated with their own anti-particle as well.

Caterina Vernieri: So let's start from the leptons. We have the electron, you're all familiar with the electron, but it comes in nature, actually with two heavier replica that are also less stable.

Caterina Vernieri: The muon and the tau, they all have electrical charge and each of them is associated to a very special particle, the neutrino. The neutrino does not have any electrical charge.

Caterina Vernieri: And they almost massless, so they travel almost at the speed of light and they really don't interact much with the other particle, so you can think of the neutrino as traveling through the earth with almost no interaction with anything else.

Caterina Vernieri: And then we have the quarks, they will charge, and again they come into three families, we have the up and down that make up the proton and the neutron, and again we have a heavy replica of these up and down quark, which are called charm and strange, top and bottom.

Caterina Vernieri: And then we have in the last column here, the force carriers, they are responsible of transmitting the information of the force among particles they're responsible of the particle interactions.

Caterina Vernieri: So let's look into them, we have the electromagnetic force that it is mediated by the photon, all the charge of the particle feels it

Caterina Vernieri: The photons responsible for electricity, magnetism, and binding together the electrons in the atoms.

Caterina Vernieri: Then we have the electroweak force that as the name suggests, is really much weaker than the magnetic force and is mediated by the W and the Z Bosons, and all the particles feel it.

Caterina Vernieri: This force is responsible of changing the makeup of the quarks and leptons so, for instance, they can transform a down quark into up quark.

Caterina Vernieri: So a proton can become a neutron, and the electroweak force is basically responsible for radioactivity.

Caterina Vernieri: And then we have the strong force that it's felt only by the quarks, and it's responsible for binding together the quarks into stable particles. That's so strong.

Caterina Vernieri: that a quark cannot exist free in nature, if , once we produce quarks at the large hadron collider, actually the strong force is so strong that gluons that mediate the strong force are emitted and then split into quarks and antiquarks until we have a spray of stable particles.

Caterina Vernieri: So gluons are essentially what keep the quarks together to form the protons

Caterina Vernieri: So what we say it's actually that protons are made up of quarks, three quarks and a certain number of gluons as well.

Caterina Vernieri: So in this picture you see that something is missing and it's something that we all experience all the time: gravity and this is because the Standard Model, as far as.

Caterina Vernieri: As we know, right now it has described so most of our data, but it falls short from being a complete theory of nature, as it doesn't include yet general relativity in the theory. Also we don't really understand fundamentally gravity that well.

Caterina Vernieri: We understand, indirectly, the effects that it has on celestial bodies, but we don't really know how it does what he does and how microscopic particles are affected by gravity.

Caterina Vernieri: And eventually what we would expect is to have a graviton that could mediate the gravitational force, associated to this force, but we have not found it yet so that's why gravity is missing from this picture.

Caterina Vernieri: And one of the latest addition to the Standard model has been Higgs boson and it's very special in this picture because it's the particle responsible of giving mass to the other particles.

Caterina Vernieri: By other means, if the Higgs boson doesn't exist, then all the particles would be massless and the universe would be very different from what we are used to see.

Caterina Vernieri: And I want to tell you a little bit about how particles acquire mass. So the Higgs boson is associated to the Higgs field as much as the photons are associated to the electromagnetic force and electromagnetic field.

Caterina Vernieri: All the particles feel the Higgs field and they are slowed down by the interaction with this field so the more they are slowed down, they acquire inertia,

Caterina Vernieri: the larger is the mass that they get. So basically, the mechanism through which particle acquire mass, it's through the interaction with the Higgs field. Stronger is the interaction, more massive is the particle interaction, that's basically it.

Caterina Vernieri: There is something special about the Higgs field, that I told you at the beginning when I tried to give you the concept of what a field is.

Caterina Vernieri: The Higgs field, it has a non zero value everywhere in the universe, which is kind of unique and this means that what we expect is that Higgs boson should collectively

Caterina Vernieri: interact and collectively form the Higgs field that fills up the whole universe, with a non zero value.

Caterina Vernieri: So one way to test it it's by experimentally try to observe events where two Higgs bosons are produced. That would be a clear hint of the collective behavior, the collective interactions of the Higgs bosons and telling us more about the Higgs field itself.

Caterina Vernieri: So why does this, it is still a mystery to us, but hopefully by observing the

Caterina Vernieri: Production of two Higgs bosons and its self-interaction, that's how we call it, the Higgs boson self interaction, probably will help us shed light around the mechanism that gives a non zero value to the Higgs field.

Caterina Vernieri: And I think I probably have build the case to explain why the higgs boson is so special and why its discovery was a major milestone for all of us in 2012.

Caterina Vernieri: It was one of the most important discovery, because finding the higgs boson at the LHC, and I'll tell you more about how we found it

Caterina Vernieri: was an incredible proof that we understand now a bit more, a bit better how particles acquire mass. It was definitely a big a big day for the two physicists, Francois Englert and Peter Higgs that had first theorized the existence of this particle in the 60s, and that they won a Nobel Prize for it.

Caterina Vernieri: Now we have, we have all the pieces of the Standard Model and what we have now.

Caterina Vernieri: We have the Higgs Boson finally discovered and all the particles that have been found in nature, so far experimentally, are all in the table that I've shown you before.

Caterina Vernieri: And all the interactions of the particles can be described by these little equation that in a very elegant way summarizes

Caterina Vernieri: all the fundamental interactions between particles, this is a very little and compact form, that can fit in a T shirt that you can buy at CERN. In the last row here I have highlighted are essentially

Caterina Vernieri: describing the interaction of the Higgs Boson with all the other particles, and this is the part that we have unlocked just nine years ago after the Higgs boson discovery. It is the part that we are probing right now to actually verify

Caterina Vernieri: the predictions of the Standard Model and hopefully understand better about, of the Higgs self interaction and the collective behavior of Higgs bosons.

Caterina Vernieri: So this is the part that we're studying now, probing now at LHC. Let's see and it's time for me to tell you how about actually how we produce Higgs Bosons.

Caterina Vernieri: So we collide protons, and the way this works is, it's thanks to special relativity. So Einstein has told us that energy can be converted into mass, so the basic of principle of an accelerator is that

Caterina Vernieri: we accelerate protons at very high energy and then, when we smash them we see an interaction of the quarks inside the proton.

Caterina Vernieri: And the energy of these particles can be converted into the mass of a massive object that we can create. We're looking for Higgs bosons, but in principle, we can create anything, also something more exotic that has not been discovered yet.

Caterina Vernieri: The large hadron collider is the biggest Caterina Vernieri: and most powerful accelerated ever build. We call it LHC, our jargon, it's 27 kilometer.

Caterina Vernieri: The ring is long 27 kilometers and it's located in Geneva Switzerland at CERN. And if you land in Geneva, you won't see the accelerator, because actually is sitting 100 meters underground.

Caterina Vernieri: And protons are accelerated at almost the speed of light, we have two proton beams circulating in the same ring going in opposite direction and colliding

Caterina Vernieri: 40 million time per second in four different points, where we have placed our big cameras to analyze the results of the collisions.

Caterina Vernieri: And CMS and ATLAS, are those two that were were designed to look for Higgs bosons so I'll mostly refer to the two of them.

Caterina Vernieri: The energy that is reached by these protons is incredible and it's a number that probably won't tell you much it's 13 TeraElectronVolts

Caterina Vernieri: To give you an analogy of how powerful this is, this is the equivalent of about three flying mosquito.

Caterina Vernieri: And the amazing part is that the energy is concentrated in space in a trillion times less space, than a flying mosquito and that's what makes the LHC very extraordinary.

Caterina Vernieri: So now, let me tell you a bit about the accelerator itself, so this is a visual of the tunnel, where the magnets are.

Caterina Vernieri: That accelerate protons almost at the speed of light, these are superconducting magnets. Caterina Vernieri: That are cooled down to 2 Kelvin, which means that the temperature of the magnet is actually colder than other space, it's one of the coldest place on Earth.

Caterina Vernieri: And this is a visual of a simulation actually, of the proton accelerated into the beam pipe, you can see here in this view the quarks and gluons inside the proton.

Caterina Vernieri: And then the two proton beams are made colliding near to the crossing point where the big camera is.

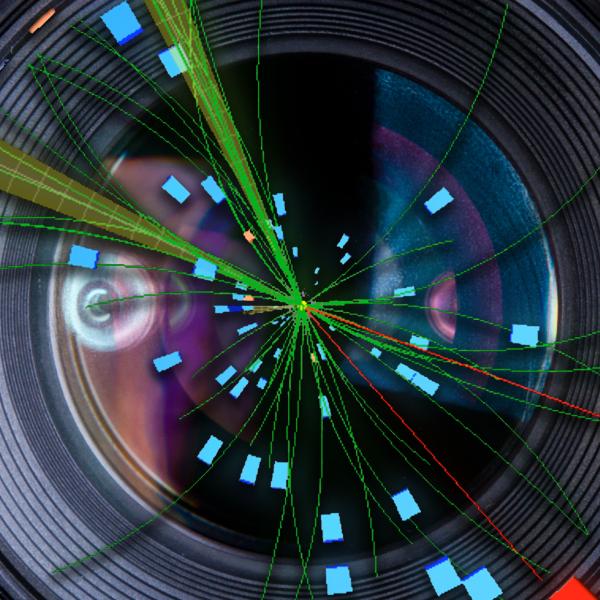

Caterina Vernieri: And the camera looks like this - if we were to do an x-ray to the camera. So different layers organized in a cylindrical symmetry around the beam interaction region.

Caterina Vernieri: So you see the two protons coming, something would be produced in the camera is this it's a it's wrapped around the beam interaction and I'll show you more about how this is built later.

Caterina Vernieri: This is just a result of the collision as we would expect something happens the proton, the proton is smashed.

Caterina Vernieri: Quarks intract, something is produced and the results of the collisions travel through the detector leaving some signals in each of the layers.

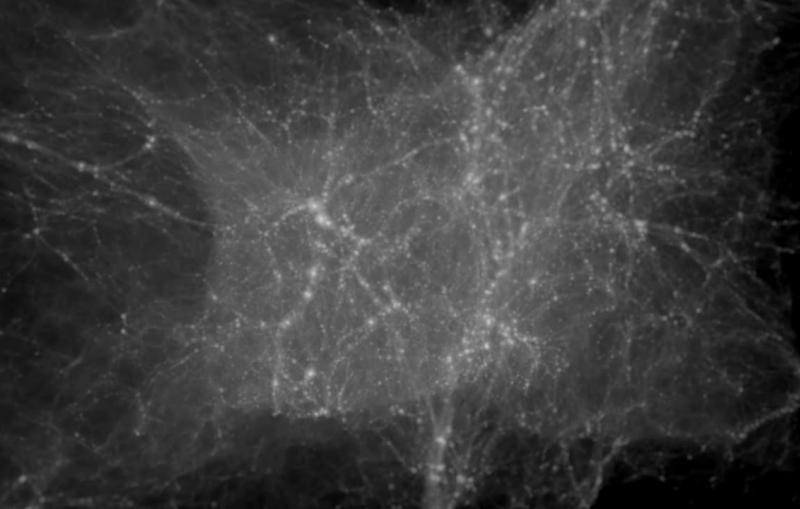

Caterina Vernieri: In this is the kind of images that as particle physicists working at LHC, we have to deal with. We don't really see a Higgs Boson, that's basically invisible to us. But we have to reconstruct the results of those collisions and understand what had been produced.

Caterina Vernieri: In reality, this is a real event. Caterina Vernieri: We have the 3D view and then a projection on the transverse plane, where you can see, like imagined that the beam is coming out of the screen.

Caterina Vernieri: And you can see, this is a beautiful image also featured on the bank notes of the Swiss bank, and what we have to do is essentially analyze particles

Caterina Vernieri: that have been produced and see what kind of event had had originated this. In reality the challenge is even larger than the simulation I have show you before, because in real life, you can see that we have lots of particles here and that's because.

Caterina Vernieri: we don't collide one proton at a time, because it will take too long to collect interesting events that are very rare to produce and have

Caterina Vernieri: low probability to happen, what we do is actually to collide a bunch of protons hundred billion proton at the time.

Caterina Vernieri: 40 million times per second, which is very impressive, you can think that LHC basically collides 2 billion protons per second.

Caterina Vernieri: putting all the math together, because at the end every time we have a bunch crossing we don't have one proton proton interaction but on average 50.

Caterina Vernieri: So, and in each proton proton interaction, we have particles that are being produced, and that's why you see hundreds and hundreds of particles here collected in the detector, in these images. So don't worry i'm going to explain to you how we get those images now.

Caterina Vernieri: And I first want to show you the kinds of images I've been looking for for almost my entire career now, since my PhD. And this is like how we're looking into our detector

Caterina Vernieri: a production of two higgs bosons, decaying to some particles, and this is the kind of events I've been interested in and i'm going to tell you now how you're going to get there.

Caterina Vernieri: First of all. Caterina Vernieri: We don't produce very often Higgs bosons in the Large Hadron Collider otherwise our job would have been way easier.

Caterina Vernieri: Most of the time we actually produce bottom quark, one in a hundred proton proton collision.

Caterina Vernieri: And one in a half a million we produce W bosons, and 1 in a million Z bosons

Caterina Vernieri: And one in half a billion we produce top quarks, And only one in a billion we produce Higgs bosons, and that's why we collide many protons per second

Caterina Vernieri: To have some hopes to actually produce some Higgs bosons in our lifetime.

Caterina Vernieri: Studying double Higgs production is even more challenging, because the probability of producing two Higgs bosons simultaneously is one in a trillion.

Caterina Vernieri: Even even smaller than the higgs boson, that's why we have not observed this particular process yet. So literally looking for Higgs bosons at the LHC it is

Caterina Vernieri: like looking for a needle in a haystack and because we are completely swamped by background processes and that's one of the challenges we have to face in order to succeed in our in our in our plan.

Caterina Vernieri: Then the second challenge is that the Higgs bosons are short lived so they die very fast in our detector and decay to lighter particle.

Caterina Vernieri: And that's why they're almost invisible to us, and the only hope we have to identify them is to reconstruct the decay chain of the Higgs boson into these lighter particles.

Caterina Vernieri: We're lucky, because the Standard model tell us which is the probability to have the Higgs Boson to decay in each of the other particles, so we know that most of the time

Caterina Vernieri: decays to b quarks, about 58% of the time and then it decays to Z bosons, W bosons with a lower probability.

Caterina Vernieri: And this is how the Higgs boson decay would look like in our detector. So what we have to deal with as experimentalists is actually to have images like this and then try to understand what kind of

Caterina Vernieri: what kind of particle are being produced and if those particles are somehow compatible with the hypothesis that an Higgs boson has been produced.

Caterina Vernieri: This is one of my favorite event that we have recorded at the Large Hadron Collider. In this is beautiful event, where the Higgs boson is producing in association with the Z boson.

Caterina Vernieri: That it's very short lived too, and it decays into an electron and a positron, beautifully reconstructed here, and then we have the Higgs boson to the b quarks.

Caterina Vernieri: So this is the kinds of images we have and now i'm going to tell you how we know that this is an electron and this is a positron and those are b-quarks, and how we get images like this.

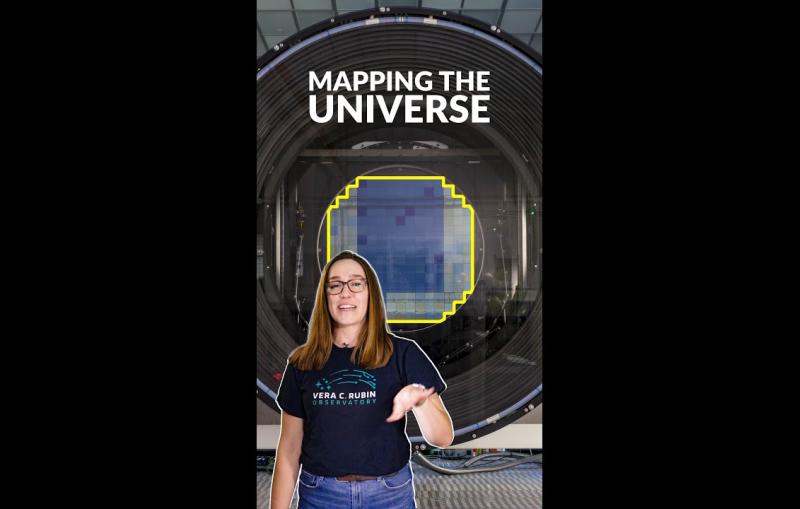

Caterina Vernieri: Our camera is a giant. ATLAS is 150 feet long and 80 feet wide.

Caterina Vernieri: It's huge. There is a human for scale, I am even too big now in this representation for ATLAS, I should be smaller to be real size.

Caterina Vernieri: It is a huge camera. The core of the camera is made of over a hundred million pixels and takes pictures 40 million times per second to match with proton rate collisions and.

Caterina Vernieri: For comparison with a five story building Just to give you more intuition, of how big it is, its bigger than a five story building.

Caterina Vernieri: The other experiments CMS, I worked on this too. Caterina Vernieri: Is that the other experiment has been designed to look for the Higgs Boson not the Large Hadron Collider.

Caterina Vernieri: it's a little bit smaller but much more heavy and both of them have been developed using different technology, what the performance they have achieved to look for Higgs bosons are equally impressive and I'm going to show you a bit about both.

Caterina Vernieri: Indeed this concept applies to both of them. It's a very general concept for cameras at proton proton colliders, so this is a section

Caterina Vernieri: of the detector, of the camera so just a section of these ones, and you have to imagine that the beam is coming at the bottom out of the screen.

Caterina Vernieri: and particles are being produced and they travel through detector. Here we can see very clearly, all the different layers of the detector.

Caterina Vernieri: We have at the very core, closest to the interaction region, the tracker detector made of silicon and that's the one we're building here at SLAC

Caterina Vernieri: for the next generation of the camera, so the tracker detector what it does is to reconstruct the trajectory of

Caterina Vernieri: charged particles and then the next two layers are designed to absorb the energy of the particles that are being produced. So here we have first the electromagnetic calorimeter that

Caterina Vernieri: measure the deposits of energy of all the particles that interact with the electromagnetic force, and then we have next to it, the hadronic calorimeter, that measures the energy of all the particles that interact with the strong force, like the proton and neutron.

Caterina Vernieri: And then we have other layers of tracker detector at the end that are made there, to in order to measure the trajectory of the particles that normally interact much in calorimeter, the muons, and to reconstruct their trajectory with more precision than just the inner tracker alone.

Caterina Vernieri: So our job, basically, is to read out each of the layer of our detector that is designed with a different technology in mind to target different particles, so we have tracking system, the electromagnetic colorimeter, hadronic calorimeter and then the muon system

Caterina Vernieri: So we collect the hits from each detector and then depending on how they correlate to each other and

Caterina Vernieri: the energy we have, the trajectory of the particle, we are, we produce particle images and then we have our we have algorithms in place that can tell us which particle had been produced compatible with those hits in the detector. So that's the kind of

Caterina Vernieri: image recognition, we have to do in order to reconstruct the particles and interpret the beautiful images that i'll be showing you.

Caterina Vernieri: And know and I want to tell you a bit more about this very complex camera, this is a very big object, as I showed you and I wanted to show you how we put this together.

Caterina Vernieri: A hundred meters underground to record the collisions of proton proton interaction, this is the CMS cavern before CMS experiment was installed so

Caterina Vernieri: This is 2004 before when before the first collisions of the LHC. So the detector had to move down.

Caterina Vernieri: Was lowered, we were extremely good precision, so you have to think that these objects are huge, these are sections of the detector. They weight more than hundred tons.

Caterina Vernieri: The biggest largest was even like 1000 tons and have to be like monitoring the vibrations, vibrations had to be monitored that the level of a few millimeters in order to not break anything.

Caterina Vernieri: And the alignment has to be very precise, this is the last piece that was lowered down and the biggest one, all together, were 15 different pieces and it took two years to put it together down in the cavern and then to align.

Caterina Vernieri: And this is a beautiful image of the end of the installation, and the thing in the middle is the tracker detector that is being inserted after all the other pieces had been built. And the tracking detector if you were to take a picture

Caterina Vernieri: before the installation will look like that it's made of 200 square meter of silicon sensors. Just to give you an idea that corresponds to roughly 70 million pixels.

Caterina Vernieri: And here I am again, this is the picture, showed you at the beginning, so that was taking a few years after installation and I was sitting next to next to the tracker detector the pixel detector.

Caterina Vernieri: The one that is literally the closest thing to the beam pipe where the proton travel that I could be, that's why it's one of my favorite, you can see all the cables that are taking the data out of the detector to be analyzed.

Caterina Vernieri: So those are very complex cameras and one aspect that is very fascinating of these experiments, is that they really require the synergy and corporation

Caterina Vernieri: or several scientists in order to build operate maintain those cameras, as well as analyze the data coming out of it, we have very complex algorithm in place that required the synchronized effort.

Caterina Vernieri: of several scientists engineers and so on, and it's about 3000 people working together and from all over the world, and this is very impressive.

Caterina Vernieri: So always very fascinating to me how we can make this works and all different time zones, so now let's go back to our goal, so we want to see how we actually look for Higgs boson at LHC.

Caterina Vernieri: And I've told you how we produce it and we have a lot of the other processes and I have told you that it is short lived and it decays

Caterina Vernieri: And we know how often it decays into different particles and how those particles should look like.

Caterina Vernieri: interacting with our detector because we understand particle matter interaction well, so we know how each of these particles should look like, which signs should leave in our detector so we know what kind of images we should expect. So our job is definitely backwards, we start from

Caterina Vernieri: this image here in the one and in the very corner and we have some hits reconstructed in our detector and some energy deposited in the calorimeters.

Caterina Vernieri: And then we can combine all this information together and with our algorithms we interpret that as a flow of particles.

Caterina Vernieri: And we can then reconstruct them as a list of potential candidates of particles that are being produced and then help us to label them.

Caterina Vernieri: This combination of hits in the detector is potentially compatible with the hypothesis that was originated by a b-quark.

Caterina Vernieri: This is the kind of analysis we do. We start from hits in our detector, we interpret them as a flow of particles and then we

Caterina Vernieri: attach them a label and then we go on and verify if these two b-quarks are for instance, are compatible to be originated by an Higgs bosons or something else.

Caterina Vernieri: One of the best way to look for Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider is actually through its decay to two photons.

Caterina Vernieri: So two photons, this is how it will look like in the detector we have these very large deposits of energy in the calorimeter, the electromagnetic calorimeter, that are compatible with the photon, this is a beautiful 3D of the whole event, so we focus on the two photons.

Caterina Vernieri: We measure, their energy and their direction and, then what we do is actually to verify if it's compatible with a Higgs boson event. So we calculate the invariant mass of the two photons.

Caterina Vernieri: And, given the energy in the direction then we can do that, the problem is that in our in our

Caterina Vernieri: collider we produce photons, can arise by. many other processes can give with the same marks as the Higgs boson decaying to two photons. So when we put together all our events that are the decaying into two photons what we see is that actually

Caterina Vernieri: If we look at invariant mass distribution, we have a lot of events in our data and a few of them that they're piling up, in this very nice peak, that is, corresponding to the Higgs boson mass, so the Higgs boson mass is 125 GeV.

Caterina Vernieri: which just to give you the scale, GeV stands for Giga electron volt, and a proton mass is one GeV, so it is much more massive than one proton.

Caterina Vernieri: This is the kind of distribution, we have to analyze to verify that if our data are compatible with the background only hypothesis.

Caterina Vernieri: Or with the hypothesis that the Higgs boson had actually had been produced, and this is literally the paper from the Higgs boson discovery.

Caterina Vernieri: So this is the the first image that we have of the Higgs boson, and this is the clear hint that we had actually produced a few events compatible with the Higgs boson mass at 125 GeV decaying into two photons.

Caterina Vernieri: Since the discovery in 2012 we actually have tried to measure all the decay of the Higgs boson to the other particles and

Caterina Vernieri: We, this, this is kind of a summary table of everything we have measured in the last 10 years.

Caterina Vernieri: So, because it's important for us to prove the interaction of the Higgs Boson with the other particles and see for instance verify if it's true that the strength of the interaction is actually proportional

Caterina Vernieri: to the mass of the particle. In this plot, has actually, is organizing all the particles as function of their mass, so the mass of the particle is on the X axis.

Caterina Vernieri: and on the y axis, we have the strength of interaction and you can see that we actually have verified this proportionality with all the particle that we have observed directly interacting with the Higgs so far.

Caterina Vernieri: Some with better precision some still need some more some more data, like the muon, then we have the tau, the bottom quark, the W and Z Bosons.

Caterina Vernieri: And this is an incredible success of our theory, so far, it seems that the Standard Model is successfully explaining how the particle is and getting mass.

Caterina Vernieri: Although why it works this way is still a mystery, and hopefully understanding, understanding more about the Higgs boson self interaction, observing those events where two Higgs Bosons are produced will help us understanding more of what's missing in the Standard Model.

Caterina Vernieri: In our plan right now is to keep analyzing Higgs bosons so we are in a technical stop, there are no collisions right now at the LHC. We hope to start at the end of the year.

Caterina Vernieri: The plan is that for the next couple of years, we will double our data set, which means that, so far, we think we have 8 million Higgs on tape.

Caterina Vernieri: And what we plan to have is collect about 60 million of Higgs bosons, then the LHC will undergo a major upgrade in order to increase the intensity.

Caterina Vernieri: Of the proton proton collisions that will help us recording more Higgs bosons in a shorter amount of time, so we hope to be able, by the end of the upgrade that it is called High Luminosity LHC by 2027, we hope to be able to start recording Higgs bosons at a much

Caterina Vernieri: higher rate, instead of 3 million Higgs bosons per year, we hope to record 5 million Higgs bosons per year, and to collect more events

Caterina Vernieri: with two Higgs bosons being produced. Of course, this doesn't come for free on the cameras and the fact that we're going to run at very high intensity.

Caterina Vernieri: what means is that we will have much more challenges to face when it comes to reconstruct our events.

Caterina Vernieri: So, increasing the rate of the collisions means that instead of colliding, I was telling you at the beginning that we collect bunches of protons, so those bunches would become even more dense

Caterina Vernieri: to maximize the probability of producing Higgs bosons, which means that, instead of having an average 50 proton proton interaction, we would have 150.

Caterina Vernieri: It means that we will have to deal with thousands of particles being produced in a 10 centimeter region, and this is a very major challenge that our camera have to face in order to be able, actually to reconstruct Higgs bosons once we produce them.

Caterina Vernieri: and this is the last part of the lecture I'm going to tell you now about the camera that we actually building here at SLAC. Part of the camera that we are going to

Caterina Vernieri: install and the goal is that we need to replace the current camera and improve the resolution of our camera in order to be able to distinguish particles that are produced nearby.

Caterina Vernieri: So basically will improved their resolution, so we improve the granularity of the innermost layers of the camera, those that I have circled there. So those are the layers that we're going to build here at SLAC, the closest to the interaction regions.

Caterina Vernieri: This new camera will have 5 billion pixels and in order to to read out all the, improve the granularity and read our all the hits that we are going to get from the particle interaction.

Caterina Vernieri: I want to give you a little bit of an idea of how a pixel silicon sensor works, and this is the basic unit of our camera.

Caterina Vernieri: So basically what we have it's that the silicone sensor is arranged in a way that we have the charged particles traveling through it.

Caterina Vernieri: And it loses energy ionizing and essentially release charged particles that are collected by the front end electronics, that is directly coupled to the to the sensor. It's a matrix like the one I show here so basically we have a matrix which is

Caterina Vernieri: less than an inch square and we have little pixels directly coupled to these, are pixel sensors very highly regulated that are directly coupled to the front end electronics and

Caterina Vernieri: the segmentation I'm talking about here it's down to 50 microns which is roughly the thickness of a human hair, so that's how much small, we have to go in order to be able to reconstruct all the particles that keep new currency of the detector at percent level.

Caterina Vernieri: And I want to give you some better visual of why it's important to improve the granularity

Caterina Vernieri: of our detector to improve then the physics performance. Think of the protons coming in colliding and then for simplification that we only have three layers the pixel detector here.

Caterina Vernieri: And then the collision happens and something, something interesting is produced and we have two particles traveling in opposite directions, and leaving some hits into each of the layers, those are the red dots.

Caterina Vernieri: So we use these red dots to reconstruct the trajectory of the particles. So you can easily, see now that's smaller is the red dot, the more precise we can reconstruct back to the trajectory of the particles.

Caterina Vernieri: So, up to now whatIi've told you about the pixel detector is very similar to a camera, but there are two major differences.

Caterina Vernieri: So on the left, you see a picture I took a few years back with a digital camera and on the right of what like will look like an image from our pixel detector, some hits with some charge that's been detected.

Caterina Vernieri: So one of the biggest differences and on the picture I took almost every pixel had light and record them all, for the pixel detector we only

Caterina Vernieri: Have a few hits, only record information from the pixel pixel sensors that have recorded some signal so that's the first big difference.

Caterina Vernieri: In the other side, you can take with the newest and coolest camera a few thousand frames per second the pixel detector has to take picture 40 million per second and that's one of the biggest challenges that in designing a camera like this one.

Caterina Vernieri: So. Caterina Vernieri: Now let me show you the camera that we are going to build here as SLAC, so this is a 3D view of the whole camera.

Caterina Vernieri: In we have all the silicon sensors wrapped around interaction regions. The cool part is that it's actually the detector its closest to the interaction region that's why it's important that there's a very good resolution and we have those many channels to readout.

Caterina Vernieri: If we zoom in you see here that we have different structures just around the interaction region.

Caterina Vernieri: This one is big half a meter, we have the sensors just wrapped around in this geometry around the beam interaction. And then we have these rings structures, when the sensors a mounted in this other way perpendicular to the beam interaction region.

Caterina Vernieri: In zooming in, and I want to tell you a bit more about the challenges that this camera have to face in order to operate safely these pixel silicon sensors.

Caterina Vernieri: You can imagine, is that, by operating this silicon sensor what happens is that, Caterina Vernieri: they dissipate a lot of heat, so we have to take out the heat that is produced by the pixel silicon sensors.

Caterina Vernieri: And it's mostly the front end chip that produces a lot of heat, then we have to take it out, so we have to take out also the data and route the cables but additionally layer of complication is that we have to route our cooling system and those tube you see are two millimeters.

Caterina Vernieri: 0.1 inch Caterina Vernieri: diameter titanium tubes that bring in the CO2 that serves us to cool down our detector to minus minus 50 degrees Celsius in order to operate safely our electronics.

Caterina Vernieri: And routing this and developing the system and making sure that we can still detect our particles, it's one of the challenges we have a design level, make sure that everything works, and we have

Caterina Vernieri: all the components in place and clear when we have to mount them together so that we don't have interference or something clashing on a modules or things like that.

Caterina Vernieri: We are building now our first prototype we have started a couple of years ago, and now we're very getting close to assembly, the first one and that's how it'd look like.

Caterina Vernieri: This is the ring with the ring structure made of carbon fiber and

Caterina Vernieri: The green things are actually the modules the silicon pixel sensors that that arranged in the inner and the outer radii and then we have this tubes coming out these are the cooling loops.

Caterina Vernieri: And it will be tested here at SLAC, we have design a text box that will help us to producing the conditions of operations at the LHC

Caterina Vernieri: and cooling down to minus 50 Celsius. This is how it looks like it's incredibly small so here would be where the beam pipe goes.

Caterina Vernieri: In then here it's where modules are going to be arranged so it's very, very tiny object, full of electronics.

Caterina Vernieri: Sophisticated electronics. So this is how it looks like, I have a few pictures from the clean room now to show you. This is the ring that we got.

Caterina Vernieri: a few months back and this is the metrology we're doing on it, we have to control the flatness of these objects at the level of 15 micron and again same thickness as a human hair. And this is the box, we have built

Caterina Vernieri: in order to test it and to was successfully tested by Valentina that you will see, at the end in the q&a and Scott, a few months back before Covid, we actually cooled it down minus 50 and now we're getting ready actually to mount the modules.

Caterina Vernieri: In one question is okay, how do you attach modules and that's another obvious answer on the end we cannot actually use screws.

Caterina Vernieri: But we actually have to use a glue, and the glue that we can use to attach the modules to glue the modules into the carbon fiber local support has to be very special because, has the be

Caterina Vernieri: To satisfy a lot of criteria, the main one is that has to be a good thermal conduct, it has to really ensure a good thermal contact between the modules and the local support in order to

Caterina Vernieri: to help the transfer of heat, and we need to also, has to survive the radiation environment of the LHC. So we have spent a few months

Caterina Vernieri: probably a couple of years to develop this procedure, we need to control the glue with extremely precision, like each of the sensor

Caterina Vernieri: is just 20 millimeters square and we need to dispense glue at the level of per mill of a gram and we have to have an accuracy

Caterina Vernieri: In order to be, an accuracy in space, which is at the level of the micron, in order to be sure that we cover all the space under the sensors not more not less, just we are within the parameters.

Caterina Vernieri: And we have made several tests, and this is a picture of last month, where there is me working with Hannah, Rachel and Matt and all the attempts, you can see all the attempts from the table

Caterina Vernieri: that we have made in order to perfectionize our procedure and now we're getting ready actually to build our first prototype and to fully validated the design, of course, this is our collective effort.

Caterina Vernieri: At SLAC, I'm working with this team, and then we have pictures from back in the days before pandemic, where we can gather together.

Caterina Vernieri: And here is a picture, how the whole community that is putting together the inner layer of the pixel detector.

Caterina Vernieri: It is mainly a US effort, we are building it here at SLAC and these are all our colleagues from other institutes that were visiting our lab just a few months before Covid last year.

Caterina Vernieri: So with the new camera and more data from LHC what we hope to do is to actually identify more and more of these events, where we have two Higgs bosons being produced each of them decaying to b quarks.

Caterina Vernieri: This is a candidate event from a couple of years ago, and we hope to see more of this in the future, and hopefully the Higgs boson will actually guide us

Caterina Vernieri: Through some unexpected features, some unexpected forces, some unexpected signs in our data of new physics and something that Standard Model is not able to explain yet and

Caterina Vernieri: We also hope to produce something completely new I told you at the beginning that to one we

Caterina Vernieri: collide protons, we can produce anything, and we can also still looking at the LHC

Caterina Vernieri: For new particles, not in the Standard Model yet that they can decay to lighter particles and we can detect them by looking at the decay into some other some other particles.

Caterina Vernieri: So we're also doing this at the LHC, although the Higgs boson is my favorite topic, but the LHC is the place where a lot of searches are ongoing for new physics.

Caterina Vernieri: And LHC essentially what it does is to recreate the condition of the universe, right after the big bang.

Caterina Vernieri: So a trillionth of a second after the big bang the universe was very different from now, of course, it was very hot and dense.

Caterina Vernieri: and quark and particles were essentially existing in their free state and able to interact with one another, before more complex structures would form and

Caterina Vernieri: evolve in the way we know so that's why it's really important for us to probe matter at very high energy to understand better

Caterina Vernieri: the fundamental interactions and the how particles got together in how they acquired mass and probably hopefully that will help us shed light on the Higgs boson mechanism and the Higgs field in general

Caterina Vernieri: In conclusion, I want to tell you a bit more about the future, I've shown you.

Caterina Vernieri: our roadmap before that was going up to high luminosity LHC

Caterina Vernieri: Of course, these are very complex projects and we are thinking now on what we could do beyond high lumi LHC

Caterina Vernieri: of in order to achieve a higher energy and continue our exploration of the fundamental particles at the very high energy.

Caterina Vernieri: and bringing the time the clock back to closer to the big bang in order to understand better the mystery of the fundamentals laws of

Caterina Vernieri: the elementary particles, how they got together and so on, and again this is our very complex projects, so the planning is starting now to identify the technologies that we would need in order to be able to achieve those.

Caterina Vernieri: And this is a part of the process that is actually currently ongoing all over the word to understand the priorities of the future of our field.

Caterina Vernieri: And with this I think I have I'm concluding everything I wanted to tell you, and it's probably time to hand this back to Michael for the q&a.

Caterina Vernieri: Thank you so much for listening. michael peskin: Well, thank you very much for this beautiful talk um I probably you should introduce the panelists we have two of your colleagues here from SLAC who are going to also answer the questions.

Caterina Vernieri: yeah Okay, I was not ready for that, so all right, so Valentina, I showed you a picture of her, Valentina is a a postdoctoral fellow in our group and we're working together on.

Caterina Vernieri: on ATLAS, looking for events where two higgs bosons are produced, no surprise here, and she also, I showed you a picture, she's working in the clean room building and testing the first prototype of the inner pixel detector.

Caterina Vernieri: And Ariel, I feel bad introducing Ariel.

Caterina Vernieri: He is a scientist in the in the group, we don't really directly work together but enjoy taking Ariel a lot, he's knowledgeable in many things.

Caterina Vernieri: In things I have not talked to you about here, for instance, he knows a lot about how we have to select particles online.

Caterina Vernieri: In order to enhance our ability to retain Higgs events or more interesting events and he's an expert in particle reconstruction in the LHC ATLAS experiment so.

michael peskin: Thank you very much we've got lots of questions, but maybe, those of you in the audience, who also have your questions, please notice at the bottom of your screen there's a Q&A

michael peskin: thing to click if you click that you'll get a little window and you can type your question into that and then we'll ask those questions in succession.

michael peskin: So let's begin the first question actually i'd like to take my perfect my prerogative as the host to answer the first question, so the first question by Rod is is the boson particle the same as what is known as the god particle.

michael peskin: And the answer is yes Leon Lederman one of the early great contributors to neutrino physics invented this name the god particle for the Higgs boson and used it in the title of a book.

michael peskin: Many physicists are very uncomfortable with this, I don't like to refer to the Higgs boson and God, in the same sentence.

michael peskin: But once I attended a seminar given by the actor Alan Alda who's taught a lot about how scientists could better communicate with the public and I told him about how uncomfortable I was with this, and he said you just have to embrace it.

michael peskin: So it's the god particle. michael peskin: Okay um let's go to the then the next question i'm.

michael peskin: Tawanda would like to know when sending particles in the round collider, how do you get the centrifugal force to ensure that it follows a circular trajectory.

Caterina Vernieri: Ariel do you want to get this one? Ariel Schwartzman: Right right right, yes, yes, very, very good question so.

Ariel Schwartzman: So basically we have to swing the accelerator, or you want to keep on the protons inside accelerate and the air

Ariel Schwartzman: is so high that one need to to put a lot of force to be able to bend this chargeparticles because they're moving close to the speed of light.

Ariel Schwartzman: And that's the reason why the colliders are so so huge imagine that you're driving your car and you want to you want to make a turn and the faster.

Ariel Schwartzman: you're driving your car the, the larger the curvature has to be in order to keep the particles inside the particle accelerator so so so we have to use this huge.

Ariel Schwartzman: superconducting magnets that Caterina mentioned, to be able to to bend these particles moving almost at the speed of light and keep them inside the tunnel.

Caterina Vernieri: yeah and maybe to add a visual, so we have sections of magnets right over the over the circumference so in a small we we accelerate them in a circular trajectory by small steps.

Caterina Vernieri: With most small segment linear segment so that's why it's not a way to compensate is a fact and achieve the same color collision.

michael peskin: Carol would like to know what does anti-matter have to do with these interactions.

Caterina Vernieri: Well, when we produce when we produce particles at the LHC we produce

Caterina Vernieri: we collide protons right and we smash them and we have quarks and anti-quarks in the proton that interact and give origin to

Caterina Vernieri: particles like top quarks, Higgs bosons or other things and every time there is a Higgs bosons decay, I didn't mention that I didn't make actually clear distinction, but when, in the case of b-quarks actually decays into b-quarks and anti b-quarks. So we do produce

Caterina Vernieri: particles and anti-particles equally in our collisions and

Caterina Vernieri: Each of the particle in the standard model has its own anti-particle and we do

Caterina Vernieri: reconstruct them all and they had just that opposite charge and and we we know how to reconstruct them all in our camera.

michael peskin: Actually it's really amazing there's very complicated pictures, about half of the particles that you see are anti-matter. Yeah.

Caterina: that's true. michael peskin: Ryan, would like to know if the probability for producing a higgs boson is so low, how can you be sure that it's actually a higgs boson instead of random error.

Caterina Vernieri: that's an excellent question and. Caterina Vernieri: We do have in place a lot of statistical tool in order to ensure that what we have it's actually a signal and not a fluctuation in our data.

Caterina Vernieri: We have had cases in which our data would just fluctuate and and then by adding more data, we would say that was not compatible with an actual signal but was actually

Caterina Vernieri: Just a fluctuation and noise. And our statistical tools, are such that, when we claimed the observation of the Higgs boson.

Caterina Vernieri: We had we had a test hypothesis to judge if our data were compatible with a background only hypothesis or a background plus a higgs signal hypothesis and.

Caterina Vernieri: In the probability that our data were described by only the background was one in 3.5 millions so that's how much we were sure that the particle I showed before in the Higgs Boson, the nice peak, was actually the Higgs boson decay.

Caterina Vernieri: And Ariel is an expert in statistics so I'm sure probably he can add a few fun facts about it.

Ariel Schwartzman: No, no, no, it says one thing to add, I mean this is why we have to take a lot of data and run this experiment for a long time when we're looking for rare processes, like the higgs boson.

Caterina: Okay. michael peskin: Regina is interested in what she's heard about the dark matter of the universe and she'd like to know, are there differences in the way that dark matter interacts with the higgs field versus particles of normal matter.

Caterina Vernieri: that's another beautiful question um yeah I did not mention it very explicitly, so we are testing the coupling of Higgs bosons how the higgs boson would interact with all the particles, we know of.

Caterina Vernieri: We don't know yet what originates dark matter, but we know that potentially can be produced at the large hadron collider and that's one of the other exotic things

Caterina Vernieri: Some scientists working at the LHC are working on. Understanding if actually the higgs boson could be coupled to some dark matter

Caterina Vernieri: dark matter particle in that would be a very peculiar signatures, where we would see the Higgs boson decaying into nothing and that's a very interesting signature.

Caterina Vernieri: and actually at SLAC I think Ariel you are working on that right?

Ariel Schwartzman: Yes, so so right there are various models theoretical models that predict potential.

Ariel Schwartzman: interactions between the higgs boson sand particles that could be candidates for dark matter, so so one of the interesting interesting things that we, we can do.

Ariel Schwartzman: Is not only to establish the higgs boson but also utilize in as a tool to see whether the higgs boson maybe coupling to particles that could be candidates for dark matter, so we are doing the things

Ariel Schwartzman: Simultaneously, or the LHC we have dedicated analysis, like the ones Caterina described.

Ariel Schwartzman: Focusing on the higgs boson measurements and properties and we have all their analysis, where we look for specific signatures that we will see the detector if there is a interaction between a higgs boson and dark matter particles, for example.

michael peskin: Okay um there's someone in the audience, who would like to know the answer to the following question.

michael peskin: If the higgs boson gives mass to every particle, why are they so hard to see why is it that out of every billion events there's only one higgs boson.

michael peskin: and michael peskin: Is that it seemed to him or her, that would be easier to see this particle if it's responsible for all mass you have a response to that it is the prediction of the standard model.

Caterina Vernieri: yeah. Caterina Vernieri: It's another interesting question. Caterina Vernieri: We that's what.

Caterina Vernieri: The probability that's coming out of Caterina Vernieri: the standard model and because of, we produce we studied quark quark interactions, basically we collide quarks and gluons and there are many other things that can happen, dominated by the strong force, that can interact in a very high probability.

Caterina Vernieri: Interesting events that with a mediated by the weak force were originated the higgs bosons.

Ariel Schwartzman: Maybe I can. Ariel Schwartzman: complement that with the fact, I mean it's just very hard to produce the higgs boson at LHC I mean part of the reason is that.

Ariel Schwartzman: The main mechanism to to produce a higgs boson depends on the type of colliders So here we have a hadron collider and, in this case it's a proton proton collider and the main mechanism is through gluons.

Ariel Schwartzman: That interact, but if you remember from the earlier slides from Caterina, the gluen doesn't have a mass.

Ariel Schwartzman: So, so there is not a direct interaction between the the gluon and the higgs because of the lack of mass one needs to go to what is called higher order processes.

Ariel Schwartzman: in which they are virtual particles in between, and that is just very hard to do, I mean the probability for the happens very low that contributes.

Ariel Schwartzman: To why it's so hard to produce a higgs boson at the large hadron collider. michael peskin: Maybe I should inject something here I mean you have to understand a little about the the scales of master energy in nature.

michael peskin: So the heaviest quark, the top quark, weighs 100,000 times more than the quarks inside the proton.

michael peskin: If we could build a top quark collider instead of a proton collider we'd produce much more higgs bosons it'd be much more obvious.

michael peskin: But unfortunately top quarks only live for I guess a millionth of a billionth of the trillionth of a second.

michael peskin: And then they decay into the lighter things that we have available eventually protons and electrons those are the only particles, we know how to accelerate.

michael peskin: And they're made of these puny particles the couple very weakly to the higgs boson so you know i'm sorry but that's that's what nature gives us.

Caterina Vernieri: we do what we can. michael peskin: Okay, how does one distinguish between the b-quarks and higgs decay oh from those directly generated in the primary collision.

Caterina Vernieri: And that is a beautiful question for Valentina michael peskin: Maybe I should also ask how do you distinguish between you had those quarks labeled as b-quarks...

Caterina Vernieri: yeah michael peskin: How do you know what kind of course they are it's just energy right yeah.

Valentina Cairo: yeah so we can start from the latter, and then we go to the higgs boson so identifying and tagging.

Valentina Cairo: Just as a splash of b-quark is one of the key elements of the physicists at the large harden collider, so the this particle is a typical signature in the detector and that's how we managed to reconstruct it.

Valentina Cairo: Typically, the game, we play is that we look at how the displaced are the vertices in this particle, when this particle decays compared to the primary collisions and that's one of the handles, we have, and then we built very complex algorithm, so this is one of the areas in which.

Valentina Cairo: particle physics physics uses a lot of. Valentina Cairo: artificial intelligence so that's really an area in continuous development, so this is in simple words, how we identify and I always say that a spray of particles a coming from b-quarks.

Valentina Cairo: Then from there, we want to know if this works are from the higgs boson. Valentina Cairo: And so what we're doing in analysis, for instance, when we analyze our data is one of the hundreds, we have is to check if the if two b-quarks are compatible with the mass of the higgs boson.

Valentina Cairo: So that's a way to distinguish this b-jets from the others from the ones which are not compatible with with the Higgs Boson

michael peskin: Okay Gary would like to know how stable are these silicon detectors under the intense particle flux, to which they're subjected do they have a definite lifetime?

Valentina Cairo: I love this question too so maybe I can start. Caterina Vernieri: Yes.

Valentina Cairo: Yes, yeah, so this is, this is a beautiful question because it's one of the problems we are fighting with already now at the large hadron collider.

Valentina Cairo: And so, definitely don't they don't have an infinite life they suffer a lot from radiation and so now, after a few years of data, taking out the large hadron collider we are seeing the impact.

Valentina Cairo: Of the radiation damage on our silicon detector so really when we reconstruct charged particles, is one of the.

Valentina Cairo: Key discussions in ATLAS going on, nowadays, and how do we deal with it in our next data taking before we replace the detector so definitely they suffer.

Valentina Cairo: Now what we will be doing for the new unit tracker is already you know evaluating how much radiation, we will get because the environment is much more complex is much more dense and so this would be an even larger problem, no problem in the future.

Valentina Cairo: One thing we consider when we build new detectors is how we can replace them.

Valentina Cairo: Because if they suffered too much from radiation so much that we can't tune the values anymore, we cannot, you know adjust the power, the voltages and so on, to make the detector work, then we have to take them out and substitute them.

Valentina Cairo: And Caterina was mentioning earlier on how we load the modules right the glue we use and so on, and that's one of the key features, is something that suffers from radiation.

Caterina Vernieri: yeah and we are, and we hope that glue will survive, but that's the one of the reasons, actually, that we are building a new camera we're taking the excuse, make it bigger fancier, with higher resolution.

Caterina Vernieri: But we actually need a new camera because the one that we will have, by the end of the next run beginning, that is beginning now and ending 2025.

Caterina Vernieri: The pixel detector will not be usable anymore after that additional radiation, so we need a new camera anyway anywhere, and we are making it compatible with the higher intensity that we expect.

Caterina Vernieri: Each of the parts that I mentioned to you like, even the titanium tubes and the local the local support it is made of carbon fiber.

Caterina Vernieri: The silicone also is chosen, all those choices are driven by having material that radiation hard.

Caterina Vernieri: And I also told you half the truth, when I told you that we were cooling them down during the operations because of, we have to transfer out the

Caterina Vernieri: heat from the silicon sensors, one of the other reasons is that operating that cold actually limits a little bit the damage made by radiation on the sensor, not on the electronics.

Caterina Vernieri: So yeah, we have to deal with that and we already know that half way through high lump LHC, we will have to build a new camera

Caterina Vernieri: For the innermost layers and replace it, we just don't want to think about it, for now, because we have still to build the first one, but he would not last 10 years so that we will have to be replaced after five years.

michael peskin: Good well there's another silicon question on the list, this is from Sarah I guess in in Silicon Valley, you have to ask silicon questions.

michael peskin: she'd like to know, could you tell us a little more about the specifics of the sensors what process technology is used and what do you will you see in the next generation of sensors as you go forward.

michael peskin: Maybe I should say to Sarah that if we could do these in person, you could come and after the question session will stand around in the

michael peskin: In the lobby outside the auditorium and we can talk about this in all technical detail, but I think here, I have to just ask Catarina to give a brief answer to this question.

Caterina Vernieri: OK so i'll be brief and then in case, are you can reach me out, so we can discuss this over zoom at a later time. So we're using technology that is based on an ASIC of 65 nanometers and we're going to.

Caterina Vernieri: and the wafer is 100 micron thick and we have a segmentation down to 50 microns so we have a matrix so about 200,000 pixels.

Caterina Vernieri: In roughly 20 millimeter square and those are produced and bumbled in front end for us and what we get at SLAC are sensors already assembled we don't do the assembly or inside.

michael peskin: Okay i'm. michael peskin: A member of the audience would like to know.

michael peskin: As the number of simultaneously track simultaneous tracks in a small space increases is there some point where it becomes theoretically impossible to distinguish nearby tracks.

Caterina Vernieri: Definitely it is Caterina Vernieri: Valentina, do you have that in mind?

Valentina Cairo: Well, more than a theoretical limit it's a practical limited. It is

Valentina Cairo: also related to the to the sensors themselves that we have, and then the rest, the intrinsic resolution of the detector but we've been discovering I was mentioning earlier on.

Valentina Cairo: If I an understanding the question correctly. Caterina Vernieri: Think Okay, we probably understood the question here because I thought it was like these there a point where we are limited.

Caterina Vernieri: I thought like the computational power that we have in order to analyze all the hits we have.

Valentina Cairo: yeah that's a different question, yes, so in that case, if if we are talking about the computational power is a different challenge that we tackle.

Valentina Cairo: And normally what we do is we don't we try we start with a very simple procedure we have the hits

Valentina Cairo: And we built what we call space points, but then from there on we start building small track candidates and then we clean up the environment so it's it's a sort of an active procedure.

Valentina Cairo: That that we do for reconstruction is that the charged particle trajectories and then there is an intrinsic limitation in how many clusters, we.

Valentina Cairo: contribute to the same same track and that's another place where where we use neural networks, for instance, and so on, so there are two aspects, one is related to that detector side than one is the computational part and how we do this in an algorithm.

Caterina Vernieri: yeah and we have recently started some simulations and say okay if we work to increase the intensity a little bit more for the high lumi LHC

Caterina Vernieri: How this would affect the performance of our tracker detector and reconstruction of higgs bosons to b-quarks, for instance, so we have recently done this study and what we have seen is that we are limited now by the kind of.

Caterina Vernieri: segmentation granularity because we're going to build the camera in this way right it's not that we're going to have.

Caterina Vernieri: A much finer resolution. So based on the current resolution that we're assuming if we were to increase more the intensity of our.

Caterina Vernieri: particle accelerator, there is a point where we start losing performance, so increasing like the density of the proton's by an additional 20% would actually something that already hit the limit of our current camera.

Caterina Vernieri: And that's in in eventually the goal would be to go even a finer segmentation but then that's a trade off from the amount of channels, you can read some of dangerously.

Caterina Vernieri: Because, if you have smaller pixels, then you have more channels to read out and it's a very it starts hitting the computational

Caterina Vernieri: wall that we can really analyze those data in the in a limited amount of time in order to construct our particle images so it's.

Caterina Vernieri: A multi dimensional optimization that has to take into account of the technology we have possible in the computational power that we have available.

michael peskin: Okay we're coming to the end so i'm just going to ask you a few more questions, the first one, if the higgs particle conveys mass and mass produces gravity does the higgs boson tell us something about how gravity can be incorporated into the standard model.

Caterina Vernieri: that's one of the way we hope to find hints about how to develop.

Caterina Vernieri: How to evolve, the standard model into the next Caterina Vernieri: step that would include gravity so eventually understanding more for instance, if we were at we work to produce a graviton and understand the interaction of the Higgs with the graviton and that would give us an hint. For instance there are some models that predict.

Caterina Vernieri: The existence of a graviton and that will be mediating the gravitational force in this.

Caterina Vernieri: Graviton would have a probability to decay to higgs bosons and so by observing that directly would actually shed light on how to include gravity and the interplay between gravity and the higgs sector as well.

michael peskin: There were a couple people in the question, who asked about this recent announcement by the LHCb

michael peskin: about electron universality, do you want to say just a few words about that.

Caterina Vernieri: um yeah that's very exciting to connect to connect to the previous question that's not an observation of one over a 3.5 million yet.

Caterina Vernieri: it's it has a little bit lower statistical values still very exciting, but we still need more data in order to validate that announcement.

Caterina Vernieri: To go back to the statistic question we had at the beginning it's very exciting if that's true, it may be that we have a new force.

Caterina Vernieri: That is in what we're seeing it's effect, now that is effecting differently, a flavor over another.

Caterina Vernieri: And if that's true, then what we can expect are two things that the LHC, first of all, even though CMS and ATLAS we're not designed to look for these processes, we can still look for them.

Caterina Vernieri: and someone else from ATLAS could actually probably try to perform similar analysis so with less precision, probably in trying to see if we see similar effects.

Caterina Vernieri: Or to look for additional effects in our data, because if this force exists then it should manifest itself in our data and CMS and ATLAS should be able to catch it.

michael peskin: Although Maybe I should caution, those of you in the audience that particle physicists don't consider three Sigma as proof.

Caterina Vernieri: optimism too michael peskin: This would be an amazing thing if it were true yeah. Caterina Vernieri: So we are cautiously optimistic about it, we need more data to really open the bottle of champagne.

michael peskin: And finally, the last question there's a member of the audience who's in high school and wants to study particle physics in college, do you have any advice, how can I put myself on a track to work in places like CERN and slac.

Caterina Vernieri: Well, here at connecting this to these lectures, so I would say it's a great start already I think being curious and.

Caterina Vernieri: study physics, is definitely all you can do and once you have got your basics trying to get an internship.

Caterina Vernieri: There are a lot of summer programs at CERN, SLAC, Fermilab, try to directly work with scientists on some research projects.

Caterina Vernieri: that's how it started that's how I decided, I wanted to become a particle physicist I spend my first summer at Fermilab.

Caterina Vernieri: On CDF and and that, for me, was was very helpful to decide what I wanted to do next, so I really strongly encourage you to really.

Caterina Vernieri: After you study after you have done the first exams in physics, to get experience to work on different experiments. There we have been talking about the LHC here, but there are beautiful experiments in particle physics and there might be others that might be interesting to you.

michael peskin: Okay well Caterina, Ariel, Valentina, thank you very, very much I think there's a lot of many comments on the question so that that people in really enjoyed this talk and well virtually at least we can give you a round of applause, thank you very much.

michael peskin: i'd like everyone to know that this talk was recorded and all of our public lectures can be found on YouTube. SLAC has a YouTube channel SLAC see not Slack.

michael peskin: Has a YouTube channel and one of the lines you'll see there for the slack public lecture so probably within a week the video of this lecture will appear there, and if you enjoyed it tell all your friends we'd love to propagate this knowledge outward as far as we can.

michael peskin: The next SLAC public lecture will be at the end of May it'll be on a very different subject matter and high density and we'll have the announcements out toward the beginning of May, and I hope to see you all there, thank you very much.