A day in the life of a light engineer

Knowledge of physics and a love of challenges fuel May Ling Ng’s quest for nanometer perfection in the smooth surfaces of mirrors used at SLAC’s X-ray laser.

By Stephanie Melchor

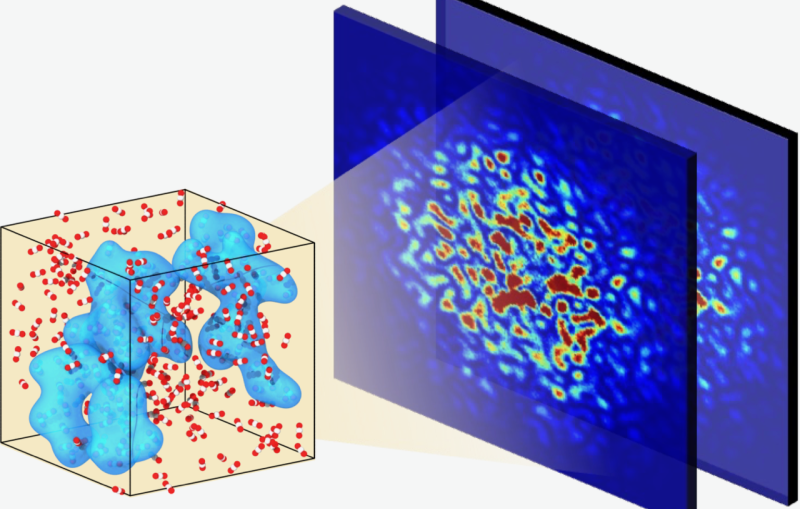

Strategically placed mirrors inside the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) are key to guiding, preserving, and focusing its free-electron laser beam, which scientists use to observe atomic-scale processes with unprecedented resolution. But to achieve this, the mirrors have to be exquisitely precise.

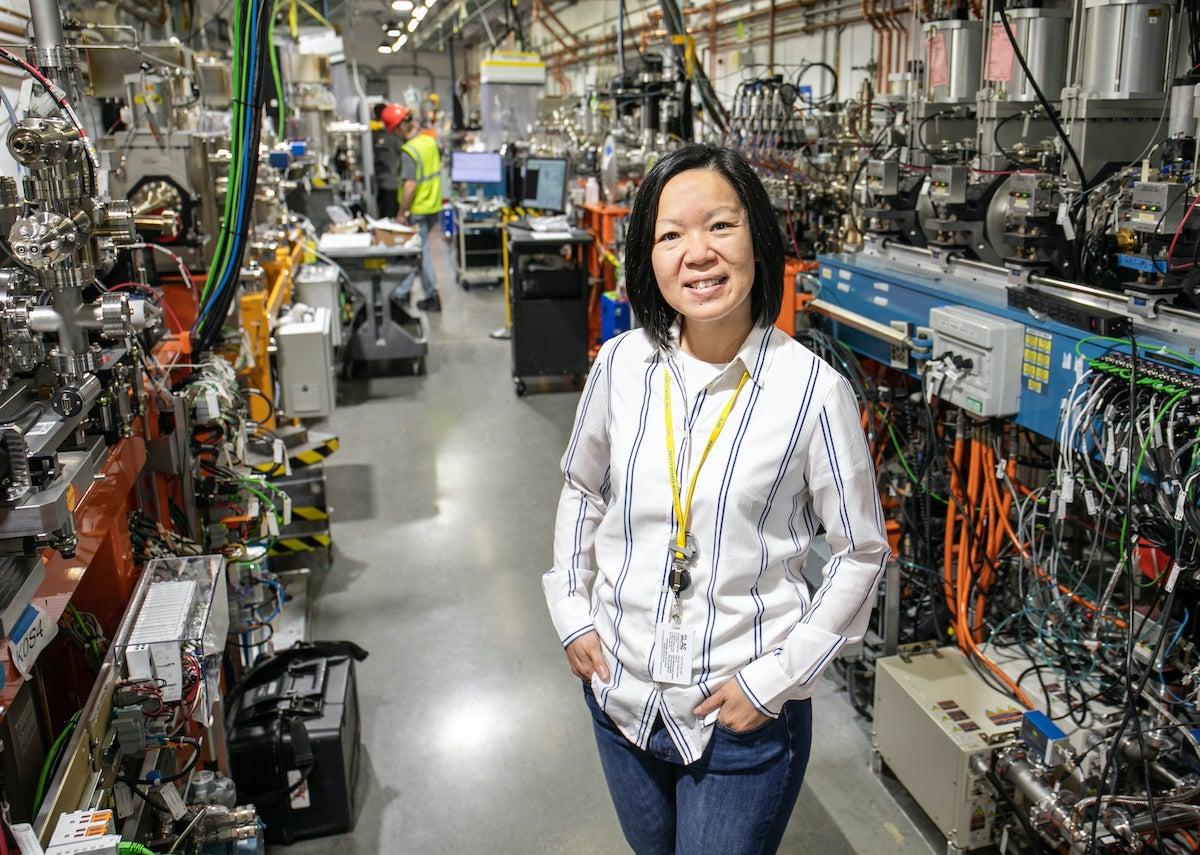

This is where the Optics Metrology Lab at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory comes in.

Staff Engineer and Optics Metrology Lab Manager May Ling Ng and her team use their own set of lasers to inspect LCLS mirrors before they’re installed to ensure the mirror shape and smoothness meet the performance requirements. The entire surface of the mirror, which can be up to a meter long, has to come within less than one nanometer, or billionth of a meter, of the desired profile.

These measurements, which are critical for ensuring the mirrors meet specifications, must be performed remotely. The mirrors are so sensitive that sharing a room with people can generate enough heat to warp the mirrors, and any movement in the room can stir up dust particles that contaminate the mirror surface.

Once the mirrors are staged on the measuring equipment, the process of making those measurements is fully automated. Ng and her team analyze the data remotely, ultimately determining whether the mirror is fit to be installed in LCLS. The process can take up to several weeks, so remote and automated measurements are also more practical.

“No human being is patient enough to sit there and click on a computer a few thousand times,” says Ng. “Without automation, it would be a very, very tedious, if not impossible, job.”

‘A challenge junkie’

Unlike the surface of her meticulous mirrors, Ng’s path to this position was anything but smooth and straight.

Ng grew up in Malaysia and became interested in mathematics and physics as a rebellious teenager.

Her father wanted her to pursue an administrative career in banking or business – something he considered to be a traditional career path for a woman. But Ng recalls being “quite stubborn” as a teenager, and wanting to follow her own path. She told him, “No, I want to do something the boys usually do!”

Boys became engineers, she thought, and set her sights on becoming one herself. As it turned out, she was quite good at mathematics and physics and graduated with honors from University Putra Malaysia, earning a bachelor’s degree in physics.

Shortly after graduating, she moved from Malaysia to Sweden, where her husband was living, to pursue a master’s degree in physics. Ng studied Swedish for a year before starting her program, since her physics courses would be taught in Swedish.

“I’m a bit of a challenge junkie,” she admits.

After her master’s, a job at the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source gave Ng her first taste of working at a light source – an accelerator that produces high energy electromagnetic beams for scientific experiments – and she was immediately hooked. Upon her return to Sweden, she was eager to jump back into work on a beamline at the MAX-Lab (now known as the MAX IV Laboratory) in Lund, Sweden. The beamline was jointly owned by Uppsala University, where she got her PhD in physics, with an emphasis on surface and materials science.

Ng was fascinated by the study of catalytic reactions at surfaces – what happens inside a car’s catalytic converter or in the life-sustaining photochemical reactions in photosynthesis.

Craving the sunshine after being in Sweden for so long, Ng moved to California to do postdoctoral research at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and then at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, and subsequently LCLS.

At first, managing the Optics Metrology Lab at SLAC seemed like a major shift from her fundamental research background, until Ng realized how well all her previous training had prepared her.

“In the end, it’s still about using mathematics to study the shape of optics that can transport and conserve the light from one point to another,” she says. “It's still very much physics – the same principles I studied in school, the same kind of mathematics and data analysis.”

‘Be a bit adventurous’

Between her academic training and various jobs, Ng has lived in three countries outside her home country on three continents. Today, it’s a good thing that she loves challenges, because her position keeps her juggling several responsibilities on top of being an engineer in metrology.

In addition to running the mirror measurements, Ng is an area manager for two metrology labs and the Front End Enclosure of LCLS – the area between the electron dump and the first experimental hutch. As an area manager, she helps ensure the areas are running safely and smoothly. In her free time, she paints watercolor landscapes, gardens, hikes and hangs out with her two cats.

Of all the hats she wears, however, one of Ng’s favorites is being a scientist.

The LCLS mirrors that she measures have different shapes, lengths and mechanics. Some are exquisitely flat, others are formed into a well-defined profile, and some are able to be bent to the desired shape from one experiment to the next, which means that no two mirrors are identical.

Ng and her metrology team have to customize testing protocols for each of the mirrors, and one of the things she looks forward to the most is going into the lab the next morning to see if a new measuring protocol worked or not.

“It’s really exciting for me,” she says.

As someone whose training took her into multiple new fields and around the world, Ng knows a thing or two about excitement – and uncertainty.

“Don't limit yourself to things that you feel comfortable with or that you know,” Ng advises. “Be a bit adventurous! It's scary at times, but it pays off, one way or another.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.