A Simple Way to Make Lithium-ion Battery Electrodes that Protect Themselves

Surprising Result Could Pave Way to Cheaper, Higher Capacity Batteries

Menlo Park, Calif. — Scientists at three Department of Energy national laboratories have discovered how to keep a promising new type of lithium ion battery cathode from developing a crusty coating that degrades its performance. The solution: Use a simple manufacturing technique to form the cathode material into tiny, layered particles that store a lot of energy while protecting themselves from damage.

Test batteries that incorporated this cathode material held up much better when charged and discharged at the high voltages needed to fast-charge electric vehicles, the scientists report in a paper published Jan. 11 in the inaugural issue of Nature Energy.

“We were able to engineer the surface in a way that prevents rapid fading of the battery’s capacity,” said Yijin Liu, a staff scientist at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and a co-author of the report. The results are potentially significant because they pave the way for making lithium-ion batteries that are cheaper and have higher energy density.

Good Nickel, Bad Nickel

Chemistry is at the heart of all lithium-ion rechargeable batteries, which power portable electronics and electric cars by shuttling lithium ions between positive and negative electrodes bathed in an electrolyte solution. As lithium ions move into the cathode, chemical reactions generate electrons that can be routed to an external circuit for use. Recharging pulls lithium ions out of the cathode and sends them to the anode.

Cathodes made of nickel manganese cobalt oxide, or NMC, are an especially hot area of battery research because they can operate at the relatively high voltages needed to store a lot of energy in a very small space.

But while the nickel in NMC gives it a high capacity for storing energy, it’s also reactive and unstable, with a tendency to undergo destructive side reactions with the electrolyte. Over time this forms a rock salt-like crust that blocks the flow of lithium ions, said study co-author Huolin Xin of Brookhaven National Laboratory.

In this study, the researchers experimented with ways to incorporate nickel but protect it from the electrolyte.

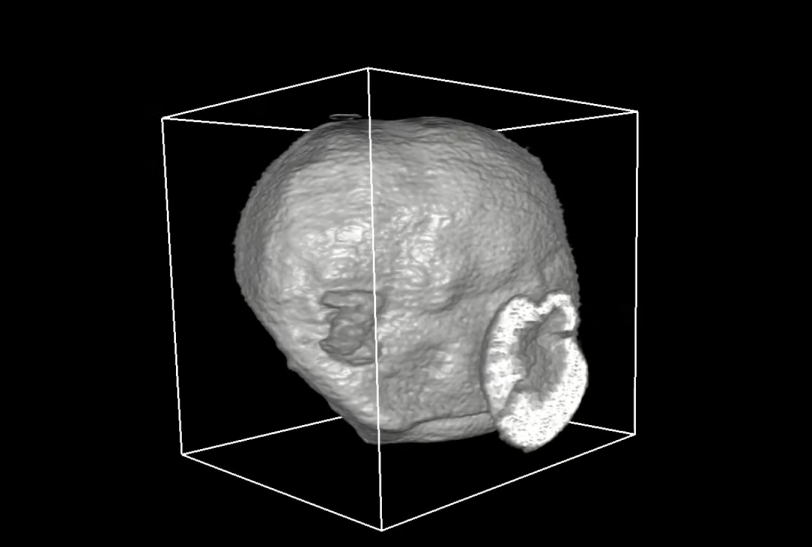

3-D rendering NMC cathode material of a battery

Particles that Protect Themselves

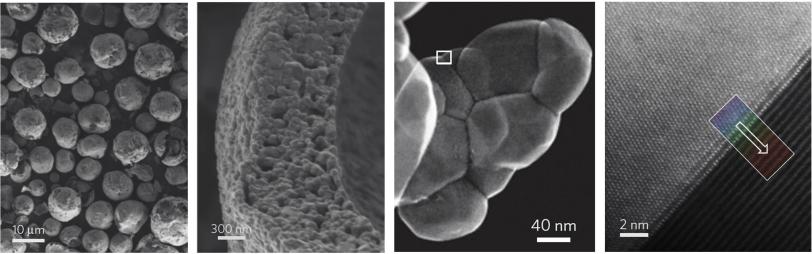

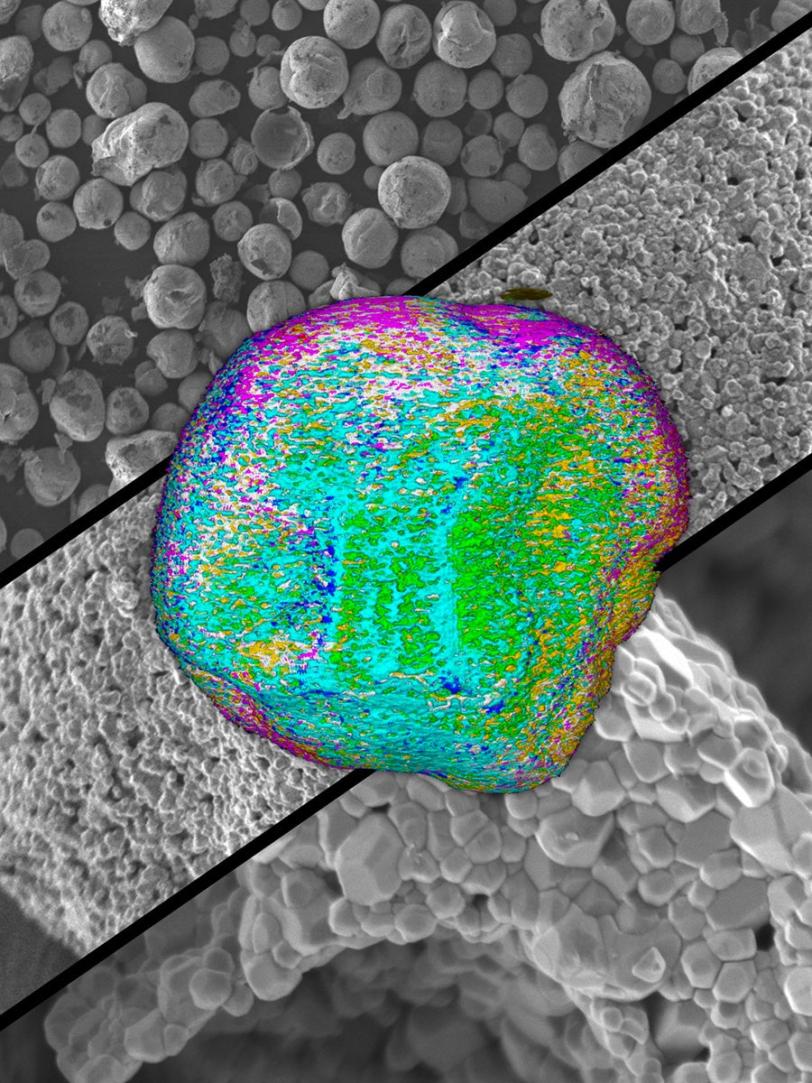

A team led by Marca Doeff at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory sprayed a solution of lithium, nickel, manganese and cobalt through an atomizer nozzle to form droplets that decomposed to form a powder. Repeatedly heating and cooling the powder triggered the formation of tiny particles that assembled themselves into larger, spherical and sometimes hollow structures.

This technique, called spray pyrolysis, is cheap, widely used and easily scaled up for commercial production. And in this case it did something unexpected. Like a cake batter that sorts itself into distinct layers during baking, the NMC particles emerged from the process with their basic ingredients redistributed.

The new structure became clear when the cathode particles were examined in detail at SLAC and Brookhaven. At SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, Liu and his colleagues used X-rays to probe the particles at a scale of 10-20 microns, or millionths of a meter. At Brookhaven’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials, Xin and his team used a scanning transmission electron microscope to zoom in on details as small as billionths of a meter, a realm known as the nanoscale.

A Simple Road to Higher Capacity

With both techniques and at every scale they looked, the particles had a different structure than the original starting material. When the SSRL team looked at tiny 3-D areas within the material, for instance, only 70 percent of them contained all three of the starting metals – nickel, manganese and cobalt.

“The particles have more nickel on the inside, to store more energy, and less on the surface, where it would cause problems,” Liu said. At the same time, the surface of the particles was enriched in manganese, which acted like a coat of paint to protect the interior.

“We’re not the first ones who have come up with idea of decreasing nickel on the surface. But we were able to do it in one step using a very simple procedure," Doeff said. "We still want to increase the nickel content even further, and this gives us a possible avenue for doing that. The more nickel you have, the more practical capacity you may have at voltages that are practical to use.”

In future experiments, the researchers plan to probe the NMC cathode with X-rays while it’s charging and discharging to see how its structure and chemistry change. They also hope to improve the material’s safety: As a metal oxide, it could release oxygen during operation and potentially cause a fire.

“To make a real, functional battery that can be commercialized, you have to look beyond performance,” Liu said. “Safety and many other things have to be considered.”

Other researchers who contributed to this work were lead author Feng Lin and Matthew Quan of Berkeley Lab; Dennis Nordlund and Tsu-Chien Weng of SLAC; and Lei Cheng of Berkeley Lab and the University of California, Berkeley. This work was supported by DOE’s Vehicle Technologies Office. SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and Brookhaven’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials are DOE Office of Science User Facilities.

Portions of this press release were based on press releases from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Citation: F. Lin et al., Nature Energy, 11 January 2016, (0.1038/nenergy.2015.4)

Press Office Contact: Manuel Gnida, mgnida@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-2632

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.