SLAC at 50: Honoring the Past and Creating the Future

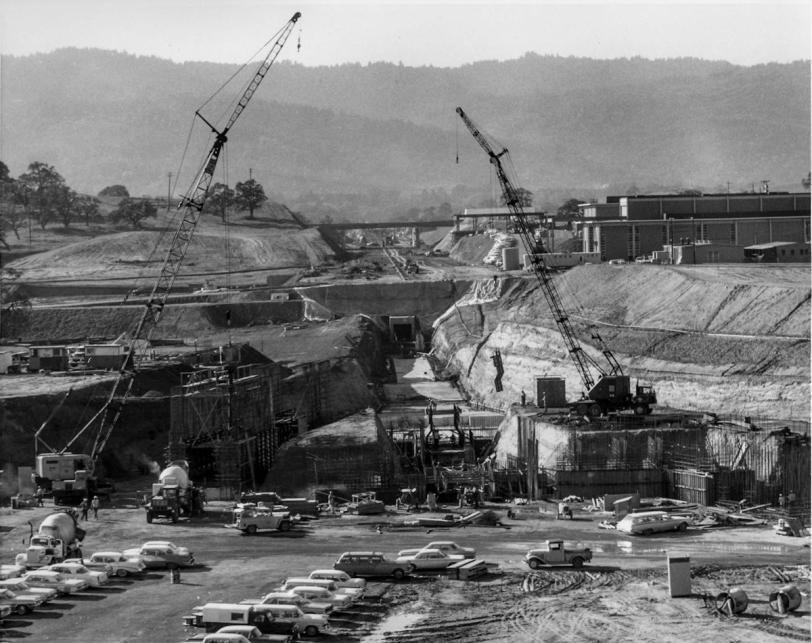

In the early 1960s, a two-and-a-half-mile-long strip of land in the rolling hills west of Stanford University was transformed into fertile ground for physicists' dreams.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

In the early 1960s, a two-and-a-half-mile-long strip of land in the rolling hills west of Stanford University was transformed into fertile ground for physicists' dreams.

They built the longest and straightest structure in the world – a linear particle accelerator first dubbed Project M and affectionately known as "the Monster" to the scientists who conjured it – to explore the mysterious subatomic realm.

Fifty years later, more than 1,000 people gathered at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory on Friday and Saturday to celebrate the scientific successes generated by that accelerator and the ones that followed, and the scientists who developed and used them.

The two-day event for employees, science luminaries and government and university leaders was more than a tribute to the momentous discoveries and Nobel Prizes made possible by the minds and machines at SLAC. It also provided a look ahead at the lab's continuing evolution and growth into new frontiers of scientific research that will keep it at the forefront of discovery for decades to come.

A history of discovery

The original linear accelerator project, approved by Congress in 1961, was a supersized version of a succession of smaller accelerators, dubbed "Mark I" through "Mark IV," that were built and operated at Stanford University. It would accelerate electrons to nearly the speed of light for groundbreaking experiments in creating, identifying and studying subatomic particles.

Stanford University leased the land to the federal government for the new Stanford Linear Accelerator Center and provided the brainpower for the project, setting the stage for a productive and unique scientific partnership that continues today, made possible by the sustained support and oversight of the U.S. Department of Energy.

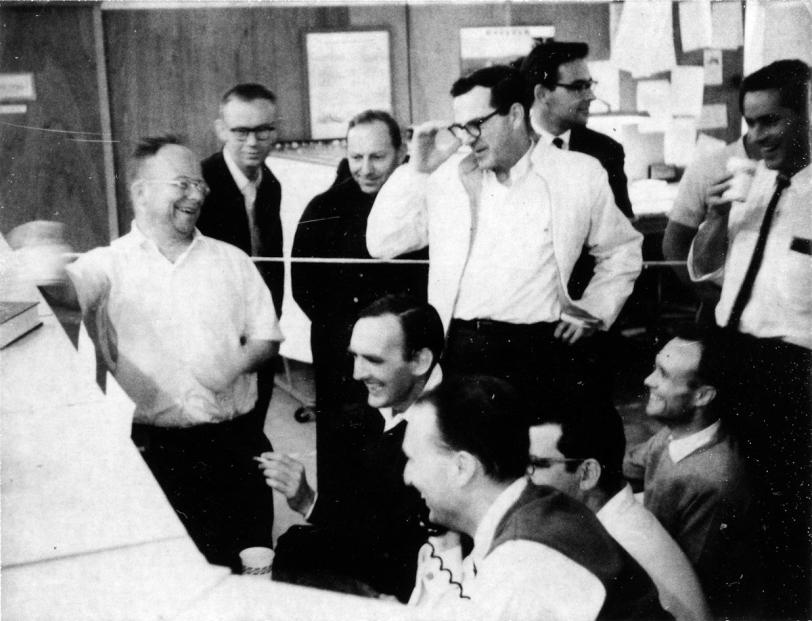

Gregory Loew joined Project M in 1958 and saw the formation of SLAC and many changes during his 50-year career, which included time as SLAC's deputy lab director. "If you asked me when I joined the project what we were going to discover with this accelerator, I didn't know,” he said. “But I fully trusted that something new and exciting was going to be found."

Soon after the new accelerator reached full operation, a research team including SLAC and Massachusetts Institute of Technology physicists used the electron beam to discover that protons in the atomic nucleus were composed of smaller entities called quarks. That research led to the 1990 Nobel Prize in Physics, shared by SLAC's Richard Taylor and Jerome I. Friedman and Henry Kendall of MIT.

A dozen years after SLAC’s founding, researchers again struck physics gold with discoveries that were made possible by another major technical feat – the addition of the Stanford Positron Electron Asymmetric Ring (SPEAR). Rather than aiming the electron beam at a fixed target, scientists used SPEAR to bring circling beams of electrons and positrons from the linear accelerator into steady head-on collisions.

In what became known as the "November Revolution" in particle physics, experiments led by physicists Burton Richter at SLAC and Samuel Chao Chung Ting at Brookhaven National Laboratory announced their independent discoveries of the J/psi particle, which consists of a paired charm quark and anti-charm quark, in 1974. They received the Nobel Prize in Physics for this work in 1976.

And in 1975, SLAC physicist Martin Perl announced the discovery of the tau lepton, a heavy relative of the electron and the first of a new family of fundamental building blocks, for which he shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1995.

The age of colliders

These discoveries and others that reshaped our understanding of matter were empowered by a series of colliders and detectors:

- The Positron-Electron Project (PEP), a collider ring with a diameter almost 10 times larger than SPEAR, ran from 1980-90.

- The Stanford Linear Collider, completed in 1987, allowed scientists to focus electron and positron beams from the original linac into micron-sized spots for collisions. The SLC hosted a decade of seminal experiments.

- PEP was followed by the PEP-II project, which included a set of two storage rings and operated from 1998-2008. PEP-II featured the BaBar experiment, which created huge numbers of particles called B mesons and their antimatter counterparts, anti-Bs. In 2001 and 2004, BaBar researchers and their Japanese colleagues at KEK’s Belle experiment announced evidence supporting the idea that matter and antimatter behave in slightly different ways, confirming theoretical predictions of charge-parity violation.

Synchrotron research and an X-ray laser

Notably, new research areas and projects at SLAC have often evolved as the offspring of the original linear accelerator and storage rings.

Stanford and SLAC researchers quickly recognized that electromagnetic radiation generated by particles circling in SPEAR, while considered a nuisance to the particle collision experiments, could be extracted from the ring and used for other types of research. They developed this “synchrotron radiation,” which came in beams of X-ray and ultraviolet light, as a powerful scientific tool for exploring samples at a molecular scale. This early research blossomed as the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Project, a set of five experimental stations that opened to visiting researchers in 1974.

Its modernized descendant, the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, now supports 30 experimental stations and about 2,000 visiting researchers a year. SPEAR, now known as SPEAR3 following a series of upgrades, became dedicated to SSRL operations 20 years ago and celebrates its 40th anniversary this year.

Roger D. Kornberg, professor of structural biology at Stanford, received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2006 for work detailing how the genetic code in DNA is read and converted into a message that directs protein synthesis. Key aspects of that research were carried out at SSRL.

SLAC’s Chief Research Officer, Keith Hodgson, joined SSRP in 1973 and has served as SSRL director, SLAC deputy director and an associate lab director for Photon Science. In the course of nearly 40 years he has participated in the growth and diversification of SLAC into a laboratory with world-class capabilities for the study of the structure and function of matter.

“The vision and determination of a few faculty and staff at Stanford and SLAC,” he said, “gave birth to SSRP, which evolved into SSRL as we know it today and along the way spawned innovative science and technology, including the concept and proof of principle for an X-ray free-electron laser.”

Meanwhile, sections of the linear accelerator that defined the lab and its mission in its formative years are still driving electron beams today as the high-energy backbone of two cutting-edge facilities: the world's most powerful X-ray free-electron laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), which began operating in 2009, and FACET, a test bed for next-generation accelerator technologies.

An expansion of LCLS, dubbed LCLS-II, is slated to begin construction next year. It will draw electrons from the middle section of the original linear accelerator and use them to generate X-rays for probing matter with high resolution at the atomic scale.

A changing mission

The late Wolfgang K. H. “Pief” Panofsky, who served as the lab's first director from 1961-84, had often noted that big science is powered by a ready supply of good ideas. He referred to this as the "innovate or die" syndrome.

In 1983, Panofsky wrote that he had been asked since the formation of the lab, "How long will SLAC live?"

The answer was then, and still is today, "About 10 to 15 years, unless somebody has a good idea. As it turns out, somebody always has had a good idea which was exploited and which has led to a new lease on life for the laboratory."

Under the leadership of its past two directors – Jonathan Dorfan, who helped launch the BaBar experiment and the astrophysics program, and Persis Drell, who presided over the opening of the LCLS – SLAC's scientific mission has grown and diversified. In addition its original focus on particle physics and accelerator science, SLAC researchers now also delve into astrophysics, cosmology, materials and environmental sciences, biology, chemistry and alternative energy research.

Outside scientists still come by the thousands to use lab facilities for an even broader spectrum of research, from drug design and industrial applications to the archaeological analysis of fossils and cultural objects. Much of this diversity in world-class experiments is based on continuing modernizations at SSRL and the unique capabilities of LCLS.

The lab’s scientists and engineers continue to actively collaborate in international projects – designing machines and building components, running experiments and sharing data with other accelerator laboratories in the U.S. and around the globe, including Japan, China, Russia, the United Kingdom, Korea, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Latin America.

The lab's longstanding collaboration with CERN in Geneva, Switzerland, provided an important spark in the formative years of the World Wide Web and led to SLAC's launch of the first Web server in the United States. SLAC is also playing an important role in the ATLAS experiment at CERN's Large Hadron Collider, an international endeavor to explore the tiniest components of matter, where the elusive Higgs particle seems to have been discovered recently.

In the area of synchrotron science, collaborations with U.S. national laboratories and with overseas labs such as DESY and KEK have contributed greatly to the development of advanced tools and methodologies with enormous scientific impact.

Expertise in particle detectors has even elevated SLAC research into outer space. SLAC managed the development of the gamma ray-detecting Large Area Telescope, the main instrument aboard the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope that launched into orbit in 2008 and continues to make numerous discoveries.

Also, the lab has earned a role in building the world's largest digital camera for an Earth-based observatory, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, scheduled to begin construction in 2014 for eventual operation on a Chilean mountaintop.

Burton Richter, who served as SLAC director from 1984 to 1999, said the fast-evolving nature of science necessitates a changing path and pace of research.

"Labs can remain on the frontiers of science only if they keep up with the evolution of those frontiers," remarks Richter.

"SLAC has evolved over its first 50 years and is still a world leader in areas beyond what was thought of when it was first built. It is up to the scientists of today to keep it moving and keep it on some perhaps newly discovered frontiers for the next 50.”

(Photo courtesy Stanford News Service)

(Credit: SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

(Photo by Richard Muffley, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

(Credit: SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)