New Tool Puts LCLS X-ray Crystallography on a Diet

A tiny device invented at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory will make it much easier for scientists to determine the structures of important, delicate proteins by greatly reducing the amount of protein needed for study.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

A tiny device invented at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory will make it much easier for scientists to determine the structures of important, delicate proteins by greatly reducing the amount of protein needed for study.

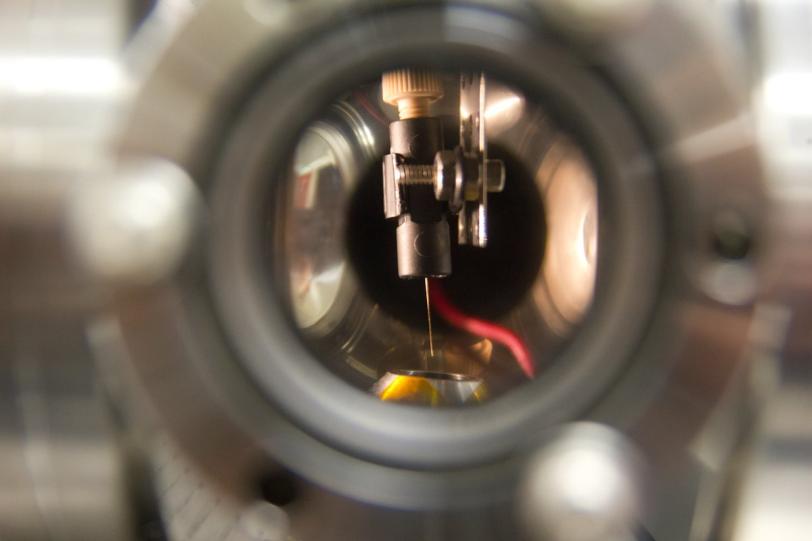

Called a microjet, the device injects a thin stream of liquid containing crystallized proteins into the path of an X-ray laser. X-rays bounce off atoms in the crystals and into a detector, forming patterns that can be used to determine the protein's atomic structure.

The new technology builds on earlier work at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source showing that the X-ray laser is a much more powerful tool for this kind of analysis than traditional methods, allowing scientists to get structural information from much smaller crystals that are easier to prepare.

By allowing scientists to perform these analyses with far fewer crystals, the new microjet will save substantial time and money and advance the understanding of important proteins that are difficult to isolate and crystallize, including many that are implicated in human disease.

"Our invention will help open X-ray lasers to more protein crystallographers, and make it easier to study the most precious biological samples," said Michael J. Bogan, a staff scientist for the Stanford PULSE Institute who led the project.

"Small, single-investigator groups often feel they may not have the funding or personnel to generate the quantity of protein required to perform crystallography at the LCLS. Our invention has removed this restriction."

The development and testing of the new microjet, known as MESH (Microfluidic Electrokinetic Sample Holder), are described in the November edition of Acta Crystallographica Section D. Stanford University has filed a provisional patent application for the technology on behalf of the team that created it, with plans to pursue licensing and a formal patent application.

In tests at the LCLS, the new system slowed the flow of samples from the microjet by 60 to 100 times. As a result, laser pulses arriving 120 times per second scored more direct hits on crystals from a much smaller number of crystals. Scientists were able to record enough data to determine the structure of a protein with just 140 micrograms of protein in a tiny volume of solution.

While the field of X-ray crystallography has been well-established for a century, experiments at the LCLS have pushed the science to new extremes by allowing researchers to probe even the tiniest crystals in high resolution at room temperature. The X-ray laser pulses are so intense and so brief – each lasting just a few millionths of a billionth of a second – that they capture detailed information about the sample's structure before destroying it.

However, this means the crystallized samples have to be constantly replenished, since obtaining the structure requires data from thousands and even millions of crystals.

In early crystallography experiments at the LCLS, a pioneering microjet developed by researchers at Arizona State University used a flow of gas to accelerate and shape the sample stream.

"The new technique complements that method," said Raymond Sierra, a Stanford mechanical engineering graduate student and lead author. "By using an electric field to shape the sample stream, and additives to keep it from breaking into droplets, we are able to create a liquid microjet without gas-focusing that flows in vacuum at about 200 nanoliters per minute," The result is a uniform stream that is thinner than a human hair.

Sierra was awarded a prize for outstanding poster presentation of the work during the 2012 LCLS/SSRL Users' Meeting and Workshops.

"The goal was to keep the crystals inside a focused liquid stream for as long as possible to ensure X-ray probing before potentially spurious effects could occur due to droplet formation," said Hartawan Laksmono, a PULSE postdoctoral scholar and co-author.

The team has already used MESH to study Photosystem II and is now working to optimize it for specific types of protein crystals such as G-protein coupled receptors, which were the target of research recently awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

For experiments at LCLS, the research team included contributors from SLAC, Stanford, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Technical University Berlin, Stockholm University, European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, and Umea University in Sweden. LCLS is supported by DOE's Office of Science.