Newly Upgraded Laser Allows Scientists to Peer Further Into the Extreme Universe at SLAC’s LCLS

Tripling the energy and refining the shape of optical laser pulses at the Matter in Extreme Conditions instrument allows researchers to create higher-pressure conditions and explore unsolved fusion energy, plasma physics and materials science questions.

By Miyuki Dougherty

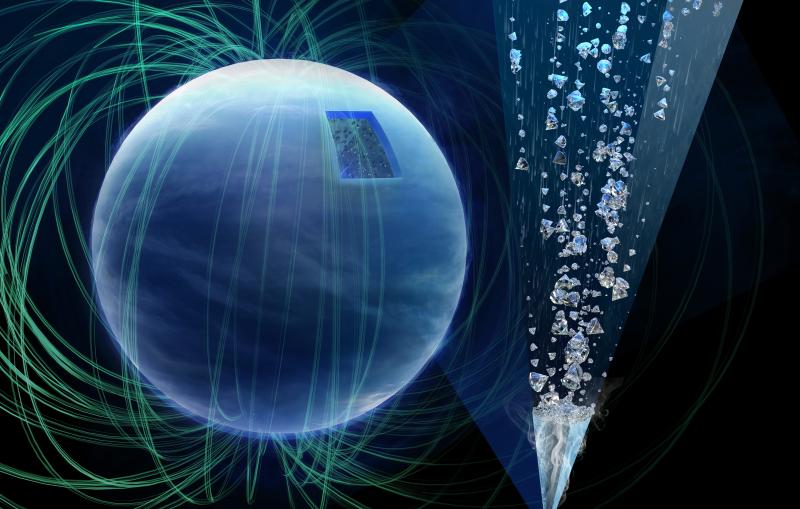

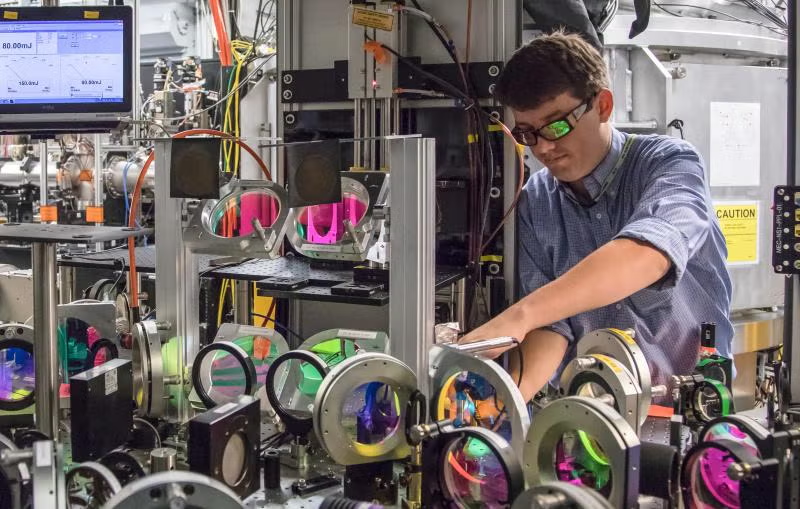

Scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory recently upgraded a powerful optical laser system used to create shockwaves that generate high-pressure conditions like those found within planetary interiors. The laser system now delivers three times more energy for experiments with SLAC’s ultrabright X-ray laser, providing a more powerful tool for probing extreme states of matter in our universe.

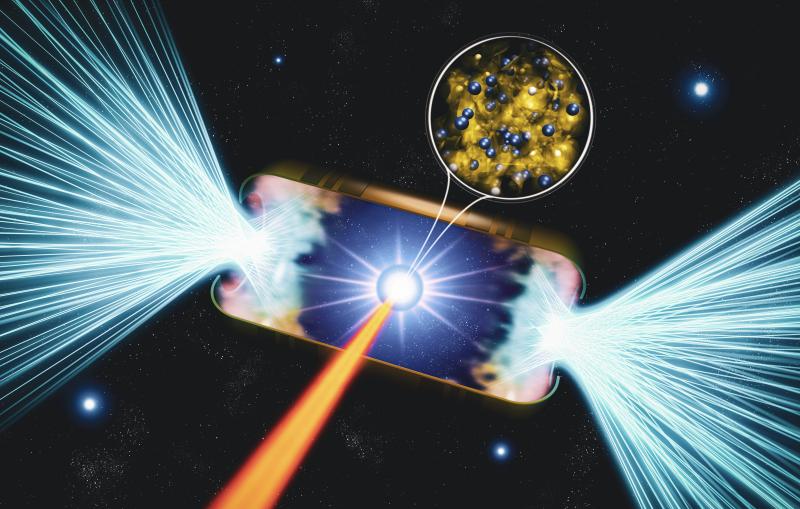

Together, the optical and X-ray lasers form the Matter in Extreme Conditions (MEC) instrument at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). The high-power optical laser system creates extreme temperature and pressure conditions in materials, and the X-ray laser beam captures the material’s response.

With this technology, researchers have already examined how meteor impacts shock minerals in the Earth’s crust and simulated conditions in Jupiter’s interior by turning aluminum foil into a warm, dense plasma.

Higher Intensity and More Controlled Pulse Shapes

The MEC instrument team received funding from the Office of Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) within the DOE’s Office of Science to double the amount of energy the optical beam can deliver in 10 nanoseconds, from 20 to 40 joules.

But they went even further.

“The team exceeded our expectations, an exciting accomplishment for the DOE High Energy Density program and future MEC instrument users,” says Kramer Akli, program manager for High Energy Density Laboratory Plasma at FES.

The team tripled the amount of energy the laser can deliver in 10 nanoseconds to a spot on a target no bigger than the width of a few human hairs. When focused down to that small area, the laser provides users with intensities up to 75 terawatts per square centimeter.

“In other terms, the upgraded laser has the same power as 17 Teslas discharging their 100 kilowatt-hour batteries in one second,” says Eric Galtier, a MEC instrument scientist.

A portion of the energy upgrade can be attributed to the optical laser’s new, homemade diode pumped front-end, designed with the help of Marc Welch, a MEC laser engineer. The scientists also built and automated a system for shaping the laser pulses with extraordinary precision, allowing users substantially greater flexibility and control over the pulse shapes used in their experiments.

A more powerful and reliable laser means that researchers can study higher pressure regimes and reach conditions relevant to fusion energy studies.

Simulating the Core of Planets

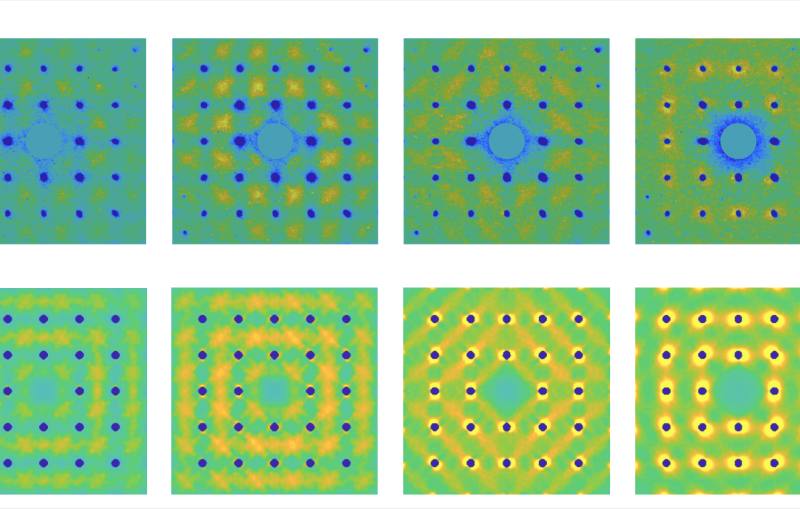

The MEC upgrade is promising for many researchers, including Shaughnessy Brennan Brown, a doctoral student in Mechanical Engineering, whose research focuses on high energy density science, which spans chemistry, materials science, and physics. Brennan Brown uses the MEC experimental hutch to drive shock waves through silicon and generate high-pressure conditions that occur in the Earth’s interior.

“The MEC upgrade at LCLS enables researchers like me to generate exciting, previously-unexplored regimes of exotic matter – such as those found on Mars, our next planetary stepping stone – with crucial reliability and repeatability,” Brennan Brown says.

Brennan Brown’s research examines the processes by which silicon in Earth’s core rearranges atomically under high temperature and pressure conditions. The thermodynamic properties of these high-pressure states affect our magnetic field, which protects us from the solar wind and allows us to survive on Earth. The laser upgrade will permit Brennan Brown to reach higher pressure and temperature conditions inside her samples, a long-standing goal.

Intensity Plus Precision

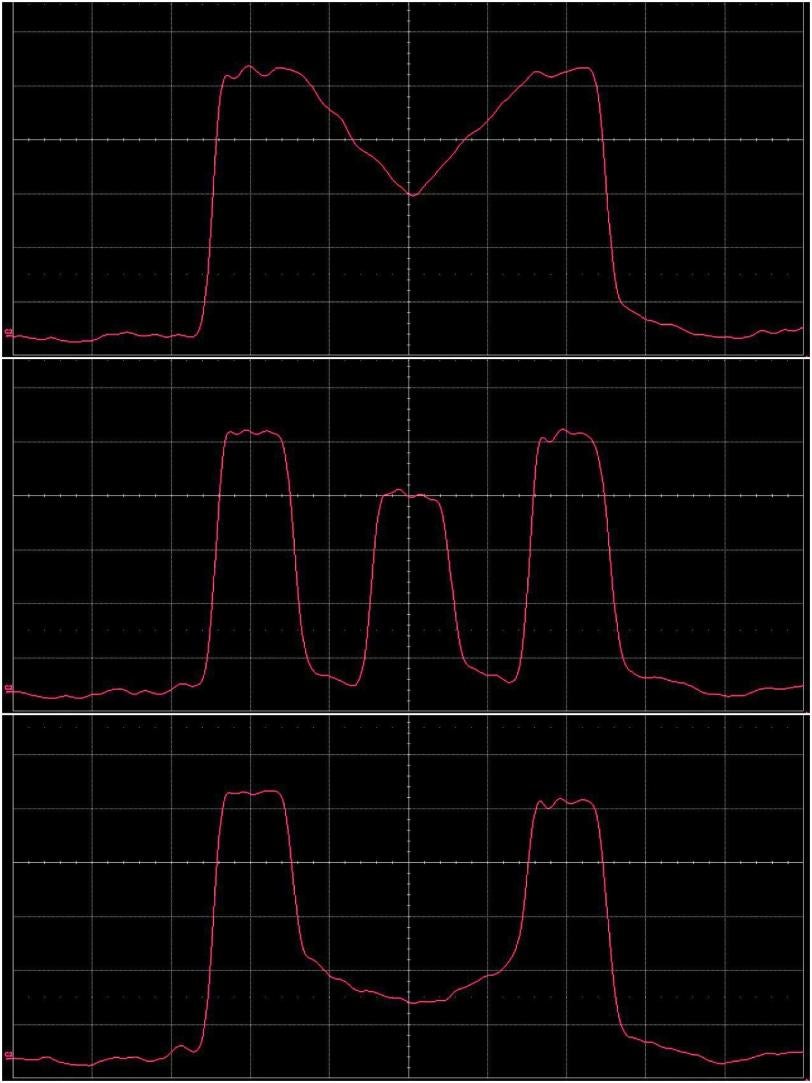

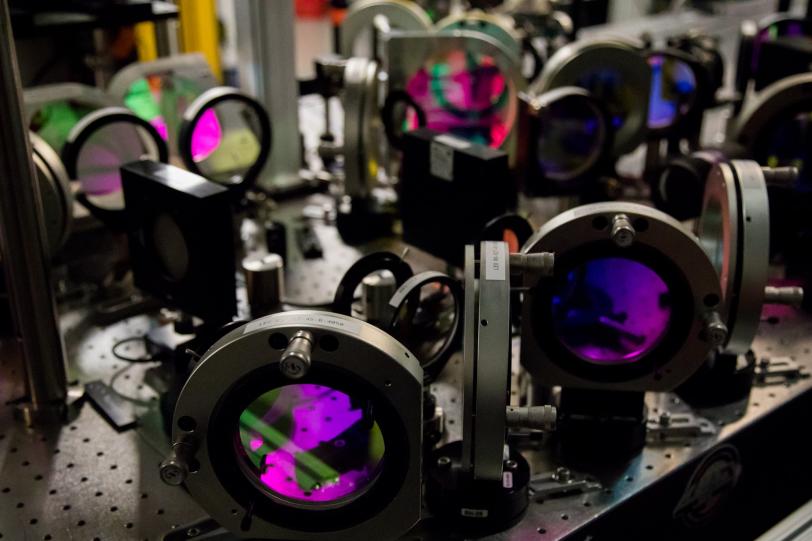

The optical laser amplifies a low-power beam in stages and reaches increasingly high energies. However, the quality of the laser beam and ability to control it diminish during amplification. A low-quality pulse may start and end with a significantly different shape, which is not useful for researchers trying to recreate specific conditions.

“The initial low energy pulse must have a pristine spatial mode and the properly configured temporal shape – that is, a precise sculpting of the pulse's power as a function of time – before amplification to produce the laser pulse characteristics needed to enable each users’ experiment," says Michael Greenberg, the MEC Laser Area Manager.

Each target is unique and requires a specific energy and pulse shape, making manual tests and adjustments time-consuming. Prior to the upgrade, the team optimized the pulse shape by hand, taking anywhere from a few hours to a few days to properly calibrate it.

To resolve this issue, Eric Cunningham, a laser scientist at MEC, developed an automated control system to shape the low-powered beam before amplification.

“The new system allows for precise tailoring of the pulse shape using a computerized feedback loop system that analyzes the pulses and automatically re-calibrates the laser,” Cunningham said. The new optimizer is a promising system for generating many high-quality pulses in the most accurate and timely manner possible.

In addition to the improved pulse shapes, the upgraded system deposits energy on samples more consistently from shot to shot, which allows researchers to very closely reproduce extreme states of matter in their samples. As a result, both the data quality and operational efficiency are improved.

Brennan Brown says it’s the people and technology that make the instrument so successful: “The capability and competency of the laser scientists and engineers at the MEC experimental station offer researchers the technological resources they need to explore unanswered questions of the universe and bring their theories to life.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.