Corrective 'Eyeglasses' Now Available For X-Ray Research Facilities

A New Type of Lens Helps Fix Focusing Problems at Widely Used Light Sources

Even when an X-ray beam is steered and focused with advanced mirrors and other optics, abnormalities can creep in. These problems have names familiar to those with imperfect vision, such as “astigmatism” or “coma” and “spherical” errors. And just like our eyes, an X-ray beam can lose power and focus when its alignment isn’t perfect.

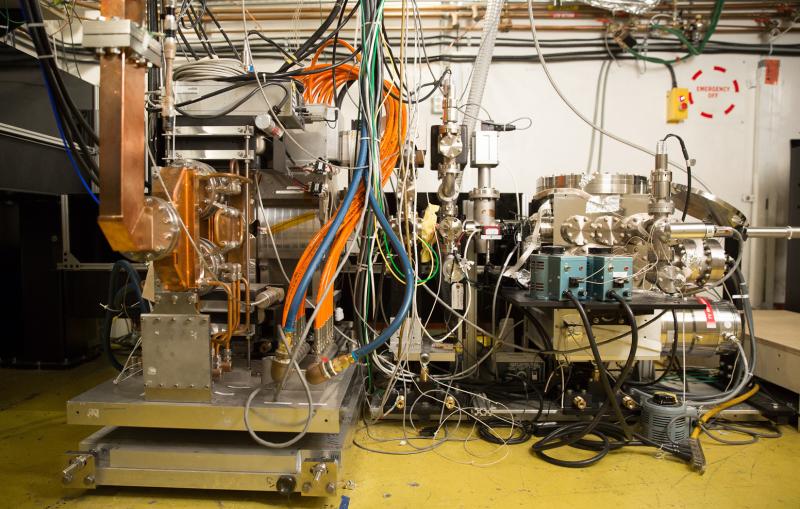

To address this challenge with X-rays, a research collaboration designed and built special spectacles, or corrective phase plates, for use at light sources that use high-intensity X-rays to probe matter in fine detail. Nature Communications published the details of the method, developed in part by researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

“Just like sight is different in every human, the optics are different with every X-ray light source and instrument,” says lead author Frank Seiboth, a researcher at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) in Germany currently on a Peter Paul Ewald fellowship at SLAC’s free-electron X-ray laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). “Once we measure the problems, then we can make corrective glasses that will make everything sharp again.”

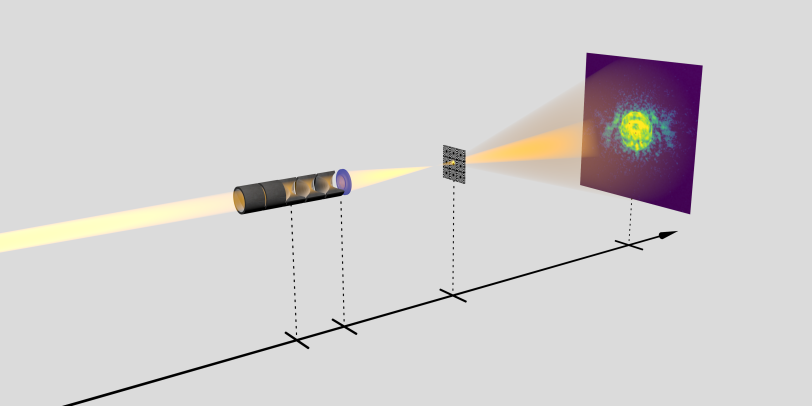

Exceptionally precise instruments form X-rays into beams intense enough for experiments conducted at free-electron lasers and synchrotron light sources. Scientists and engineers must focus the beam into a spot that may be smaller than a tenth of a micrometer, or less than a thousandth of the width of a human hair.

Because the wavelength of X-rays is much shorter than that of visible light, the production of appropriate mirrors and lenses is more challenging. Tiny shape errors can decrease the beam quality, and only a few materials are suitable for these types of optics.

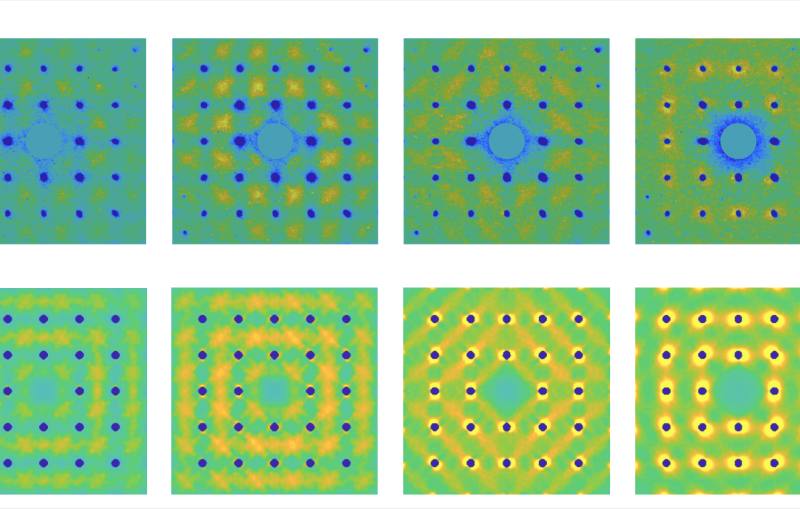

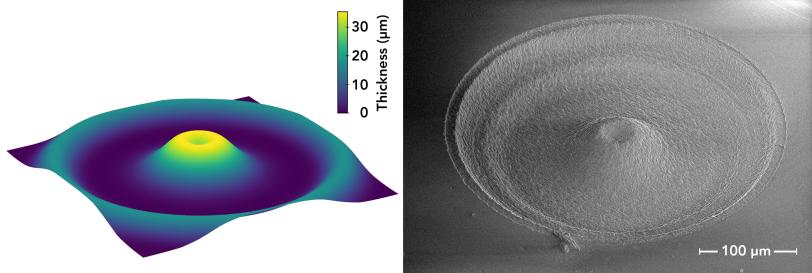

To focus the beam in this study, the scientists stacked 20 small lenses made from beryllium, one of the best available materials for X-ray lenses. Multiple lenses are needed to bend the light enough to create these tiny focal spots, due to the very weak interaction of X-rays with matter. The errors from the shape of each of these lenses add up. While this seems like a problem, it actually is easier for scientists to measure and fix the larger, combined error. The researchers were then able to collect data about the curve of the beam that informed the design of corrective glasses to refocus the X-rays.

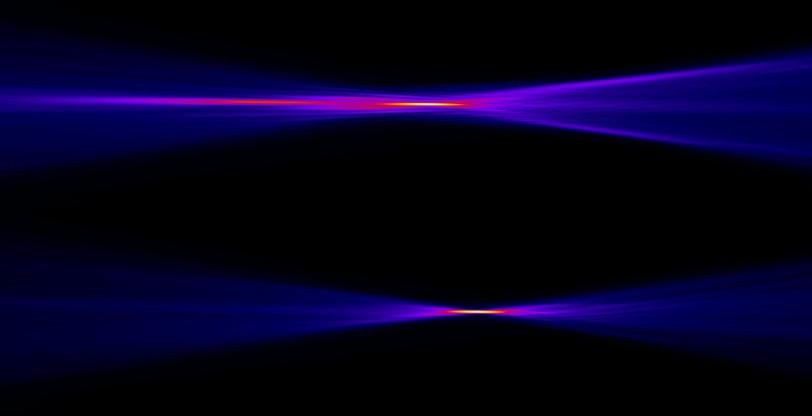

To make the precisely curved shape of the glasses that correspond to the measured error pattern, the scientists used a high-intensity optical laser to carve the corrective plates from quartz. By adding the custom-made glasses to the end of the 20-lens stack, they saw fewer deformities in the beam. While most (75 percent) of the focused beam was stretched out over an area with a diameter of 1,600 nanometers before, the researchers managed to sharpen the edges of the beam and refocus the same percentage of X-rays to a spot below 250 nanometers in diameter. And since the X-rays were more concentrated, the intensity of the beam nearly tripled.

As a test that there was no change in overall beam quality, the researchers noted that the corrective lenses did not change the sharpness in the central part of the beam, a critical measurement defined in optics as the full width at half maximum or FWHM. This remained at about 150 nanometers, with or without the glasses.

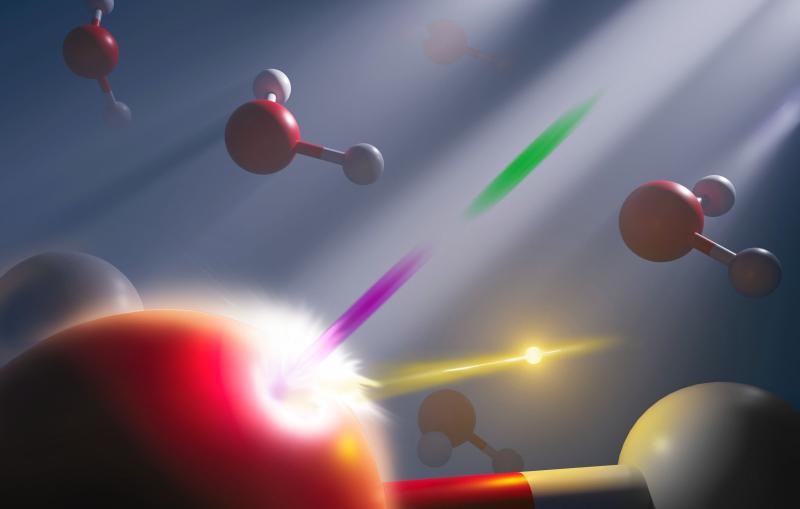

High-intensity focusing is particularly important, for example, when scientists study matter in extreme conditions and conduct nonlinear experiments where the response of the system is more complex and challenging to study, Seiboth says.

The corrective glasses can be designed for standard configurations commonly used in X-ray experimental set-ups. They were tested at LCLS, as well as at two synchrotrons—PETRA III at DESY and the Diamond Light Source in the United Kingdom. At all three light sources, the lenses worked as planned. Collaborators of Friedrich-Schiller Universität in Jena, Germany, manufactured the glasses, and the samples were prepared at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden. DESY, the Technical-University of Dresden and the University of Hamburg contributed expertise to the research.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science User Facility. The DOE Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences and Office of Fusion Energy Sciences, funded the research at SLAC.

Citation: Seiboth et al., Nature Communications, 01 March 2017 (10.1038/ncomms14623)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.