Scientists Track Ultrafast Creation of a Catalyst with X-ray Laser

Chemical Transformations Driven by Light Provide Key Insight to Steps in Solar-energy Conversion

An international team has for the first time precisely tracked the surprisingly rapid process by which light rearranges the outermost electrons of a metal compound and turns it into an active catalyst – a substance that promotes chemical reactions.

The results, published April 1 in Nature, could help in the effort to develop novel catalysts to efficiently produce fuel using sunlight. The research was performed with an X-ray laser at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

“We were able to determine how light rearranges the outermost electrons of the compound on timescales down to a few hundred femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second,” said Philippe Wernet, a scientist at Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin for Materials and Energy who led the experiment.

Researchers hope that learning these details will allow them to develop rules for predicting and controlling the short-lived early steps in important reactions, including the ones plants use to turn sunlight and water into fuel during photosynthesis. Scientists are seeking to replicate these natural processes to produce hydrogen fuel from sunlight and water, for example, and to master the chemistry required to produce other renewable fuels.

“The eventual goal is to design chemical reactions that behave exactly the way you want them to,” Wernet said.

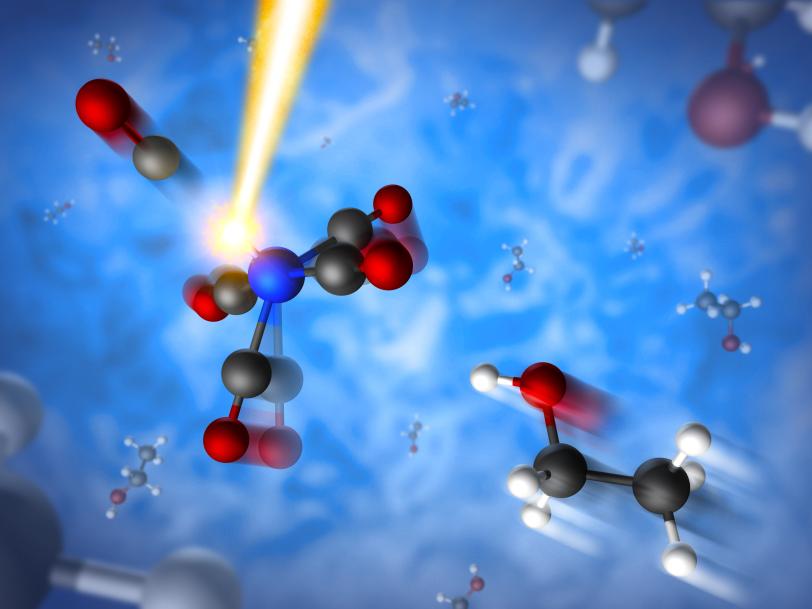

In the experiment at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, the scientists studied a yellowish fluid called iron pentacarbonyl, which consists of carbon monoxide “spurs” surrounding a central iron atom. It is a basic building block for more complex compounds and also provides a simple model for studying light-induced chemical reactions.

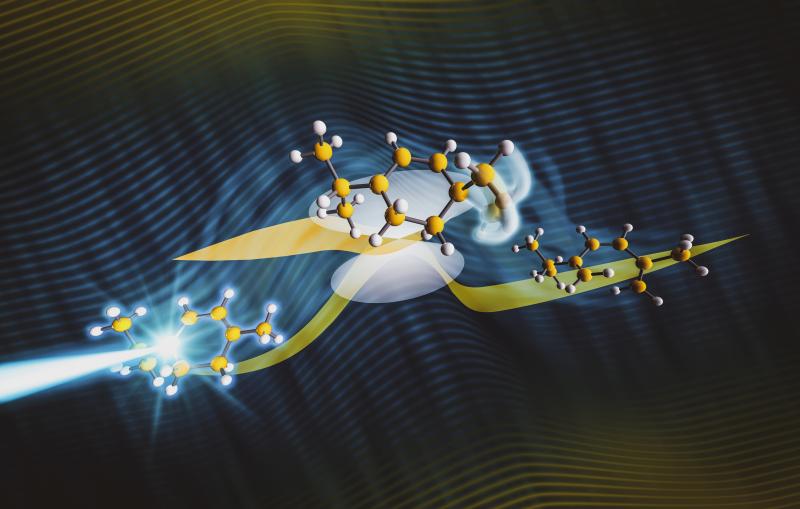

Researchers had known that exposing this iron compound to light can cleave off one of the five carbon monoxide spurs, causing the molecule’s remaining electrons to rearrange. The arrangement of the outermost electrons determines the molecule’s reactivity – including whether it might make a good catalyst – and also informs how reactions unfold.

What wasn’t well understood was just how quickly this light-triggered transformation occurs and which short-lived intermediate states the molecule goes through on its way to becoming a stable product.

At LCLS, the scientists struck a thin stream of the iron compound, which was mixed into an ethanol solvent, with pulses of optical laser light to break up the iron-centered molecules. Just hundreds of femtoseconds later, an ultrabright X-ray pulse probed the molecules’ transformation, which was recorded with sensitive detectors.

By varying the arrival time of the X-ray pulses, they tracked the rearrangements of the outermost electrons during the molecular transformations.

Roughly half of the severed molecules enter a chemically reactive state in which their outermost electrons are prone to binding other molecules. As a consequence, they either reconnect with the severed part or bond with an ethanol molecule to form a new compound. In other cases the outermost electrons in the molecule stabilize themselves in a configuration that makes the molecule non-reactive. All of these changes were observed within the time it takes light to travel a few thousandths of an inch.

“To see this happen so quickly was extremely surprising,” Wernet said.

Several years’ worth of data analysis and theoretical work were integral to the study, he said. The next step is to move on from model compounds to LCLS studies of the actual molecules used to make solar fuels.

“This was a really exciting experiment, as it was the first time we used the LCLS to study chemistry in a liquid compound,” said Josh Turner, a SLAC staff scientist who participated in the experiment. “The LCLS is unique in the world in its ability to resolve these types of ultrafast processes in the right energy range for this compound.”

SLAC’s Kelly Gaffney, a chemist who contributed expertise in how the changing arrangement of electrons steered the chemical reactions, said, “This work helps set the stage for future studies at LCLS and shows how cooperation across different research areas at SLAC enables broader and better science.”

In addition to researchers from Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin for Materials and Energy and LCLS, other scientists who assisted in the study were from: SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource; the SLAC and Stanford PULSE Institute; University of Potsdam, Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Goettingen University and DESY lab in Germany; Stockholm University and MAX-lab in Sweden; Utrecht University in the Netherlands; Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland; and the University of Pennsylvania.

This work was supported by the Volkswagen Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Carl Tryggers Foundation, the Magnus Bergvall Foundation, Collaborative Research Centers of the German Science Foundation and the Helmholtz Virtual Institute “Dynamic Pathways in Multidimensional Landscapes,” and the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

Citation

P. Wernet, et al. Nature, 2 April 2015 (10.1038/nature14296)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.