Scientists Take First X-ray Portraits of Living Bacteria at the LCLS

Researchers working at SLAC have captured the first X-ray portraits of living bacteria.

Menlo Park, Calif. — Researchers working at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have captured the first X-ray portraits of living bacteria.

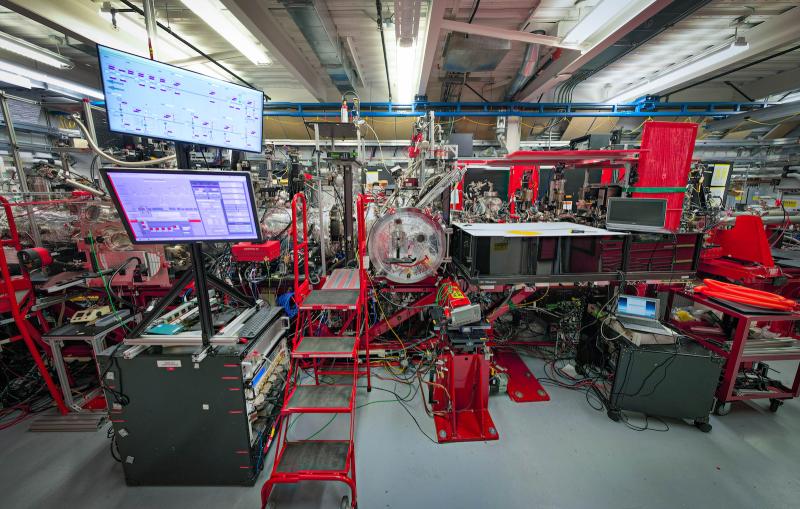

This milestone, reported in the Feb. 11 issue of Nature Communications, is a first step toward possible X-ray explorations of the molecular machinery at work in viral infections, cell division, photosynthesis and other processes that are important to biology, human health and our environment. The experiment took place at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser, a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

“We have developed a unique way to rapidly explore, sort and analyze samples, with the possibility of reaching higher resolutions than other study methods,” said Janos Hajdu, a professor of biophysics at Uppsala University in Sweden, which led the research. “This could eventually be a complete game-changer.”

AMO | Scientists Take First X-ray Portraits of Living Cyanobacteria at the LCLS

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Photo Albums on the Fly

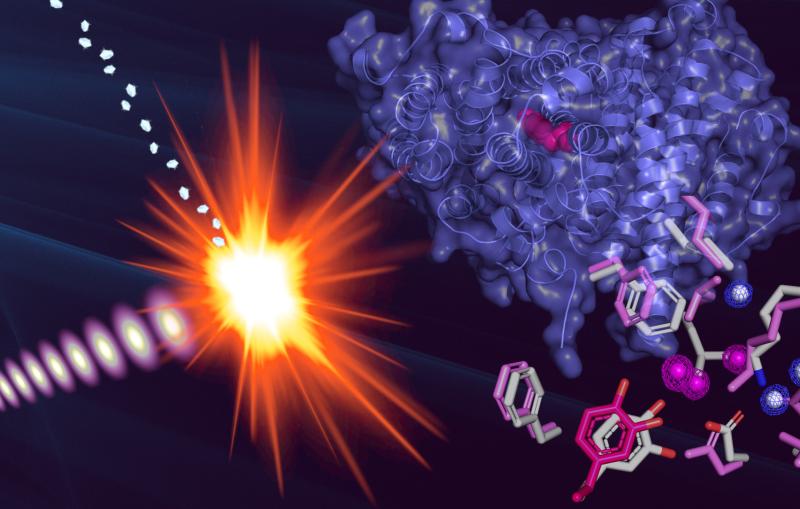

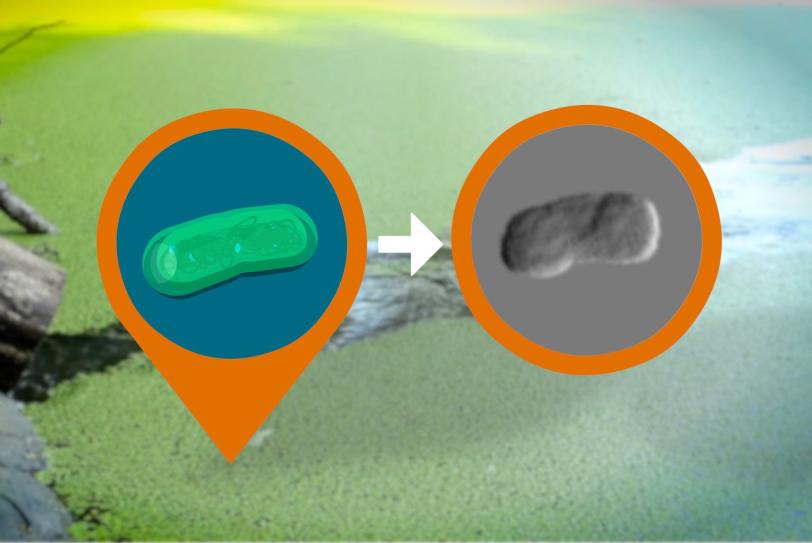

The experiment focused on cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, an abundant form of bacteria that transformed Earth’s atmosphere 2.5 billion years ago by releasing breathable oxygen, making possible new forms of life that are dominant today. Cyanobacteria play a key role in the planet’s oxygen, carbon and nitrogen cycles.

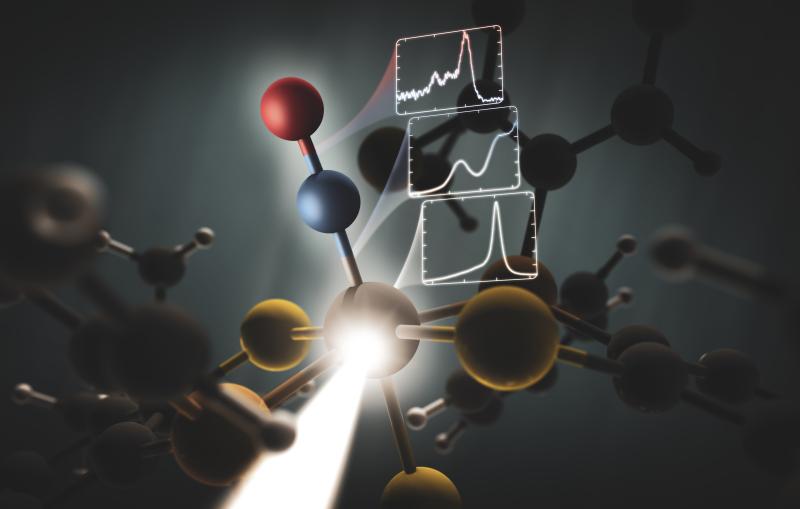

Researchers sprayed living cyanobacteria in a thin stream of humid gas through a gun-like device. The cyanobacteria were alive and intact when they flew into the ultrabright, rapid-fire LCLS X-ray pulses, producing diffraction patterns recorded by detectors.

The diffraction patterns preserved details of the living cyanobacteria that were compiled to reconstruct 2-D images. Researchers said it should be possible to produce 3-D images of some samples using the same technique.

The technique works with live bacteria and requires no special treatment of the samples before imaging. Other high-resolution imaging methods may require special dyes to increase the contrast in images, or work only on dead or frozen samples.

Biology Meets Big Data

The technique can capture about 100 images per second, amassing many millions of high-resolution X-ray images in a single day. This speed allows sorting and analysis of the inner structure and activity of biological particles on a massive scale, which could be arranged to show the chronological steps of a range of cellular activities.

In this way, the technique merges biology and big data, said Tomas Ekeberg, a biophysicist at Uppsala University. “You can study the full cycle of cellular processes, with each X-ray pulse providing a snapshot of the process you want to study,” he said.

Hajdu added, “One can start to analyze differences and similarities between groups of cellular structures and show how these structures interact: What is in the cell? How is it organized? Who is talking to whom?”

While optical microscopes and X-ray tomography can also produce high-resolution 3-D images of living cells, LCLS, researchers say, could eventually achieve much better resolution – down to fractions of a nanometer, or billionths of a meter, where molecules and perhaps even atoms can be resolved.

LCLS is working with researchers to improve the technique and upgrade some instruments and the focus of its X-rays as part of the LCLS Single-Particle Imaging initiative, formally launched at SLAC in October in cooperation with the international scientific community. The initiative is working toward atomic-scale imaging for many types of biological samples, including living cells, by identifying and addressing technical challenges at LCLS.

In addition to researchers from Uppsala University and SLAC’s LCLS, other contributors were from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; DESY, the European XFEL, PNSensor, Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and University of Hamburg, in Germany; University of Rome Tor Vergata; University of Melbourne in Australia; Kansas State University; and National University of Singapore. The work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the European Research Council, the Röntgen-Ångström Cluster, and the Olle Engkvist Byggmästare Foundation. The experiment was also made possible by the Max Planck Society, which supported the development and operation of the CAMP instrument at LCLS.

Citation: G. van der Schot, M. Svenda et al., Nature Communications, 11 February 2015 (10.1038/ncomms6704).

Press Office Contact: Andrew Gordon, agordon@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-2282

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.