Researchers find new molecule that shows promise in slowing SARS-CoV-2

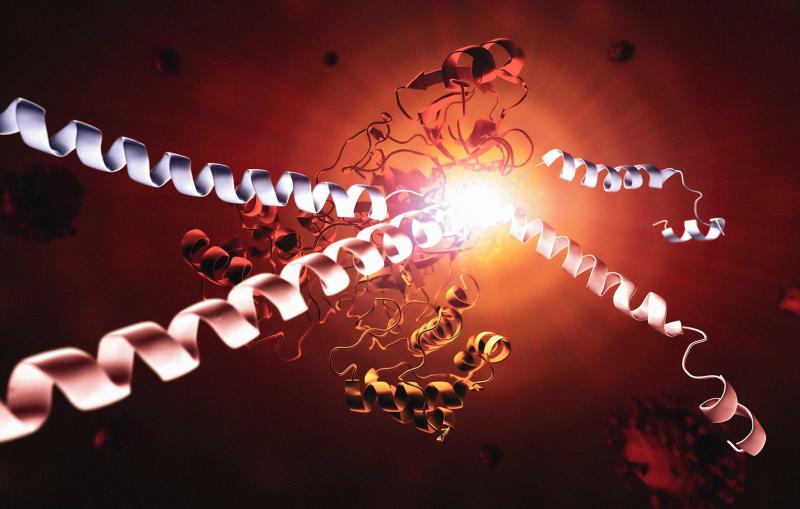

A molecule with hooks that can grip and disable the virus’s pesky protease shows potential for fighting infection.

By David Krause

Researchers have designed a molecule that slows the effects of one of SARS-CoV-2's more dangerous components – an enzyme called a protease that cuts off the immune system's communications and helps the virus replicate.

While much more needs to happen to develop a drug, scientists can begin to imagine what that drug could look like – thanks to new images of the molecule bound to the protease.

“We have been searching for an effective molecule like this one for a while,” said Suman Pokhrel, a Stanford University graduate student in chemical and systems biology and one of the paper’s lead authors. “It is really exciting to be part of the team that has made this discovery, which allows us to start imagining a new antiviral drug to treat COVID-19.”

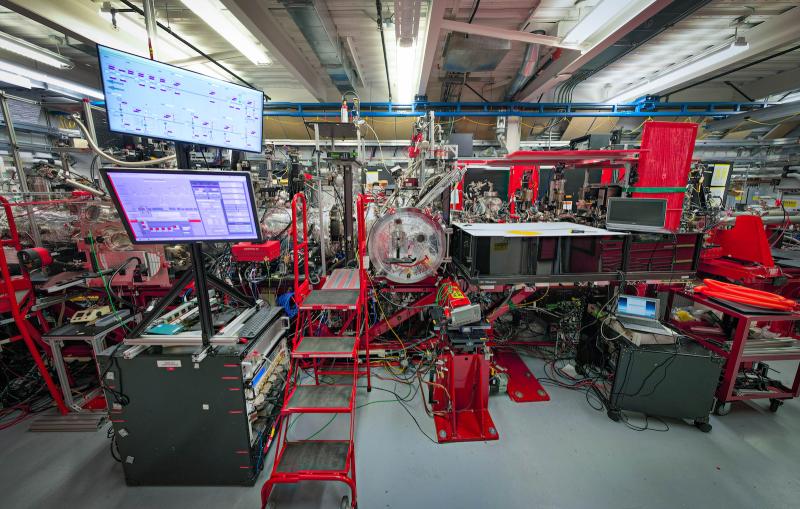

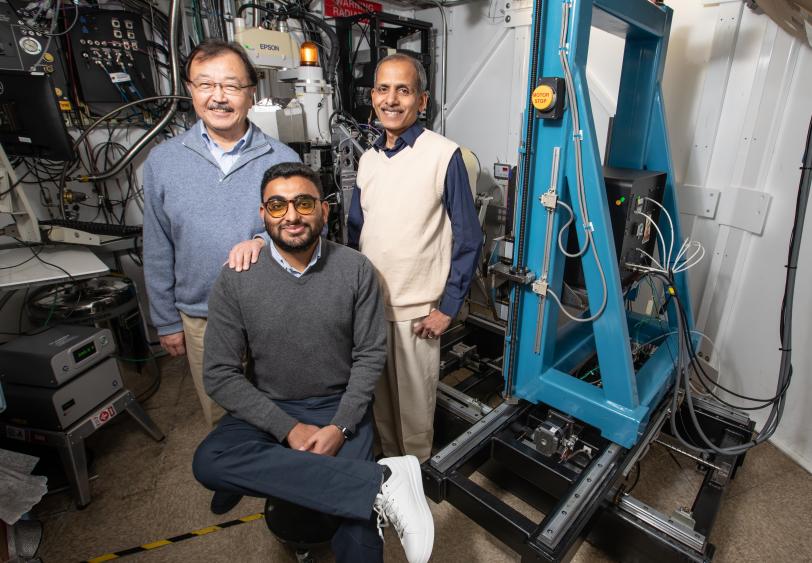

To see the atomic structure of the molecule gripped by the protease, researchers zapped a crystal sample of both with bright X-rays generated by the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. These X-rays revealed how the molecule binds to the protease. The team from SLAC, Stanford, the DOE’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and other institutions published their results today in Nature Communications.

“We designed molecules and used computational approaches to predict how they would interact with the enzyme,” said Jerry Parks, ORNL senior scientist and leader of the project. “ORNL scientists and university and industry collaborators tested the molecules experimentally to confirm their effectiveness. Then team members at SLAC solved the crystal structure, confirming our predictions, which is important as we continue improving the molecule.”

Snagging a slippery protease

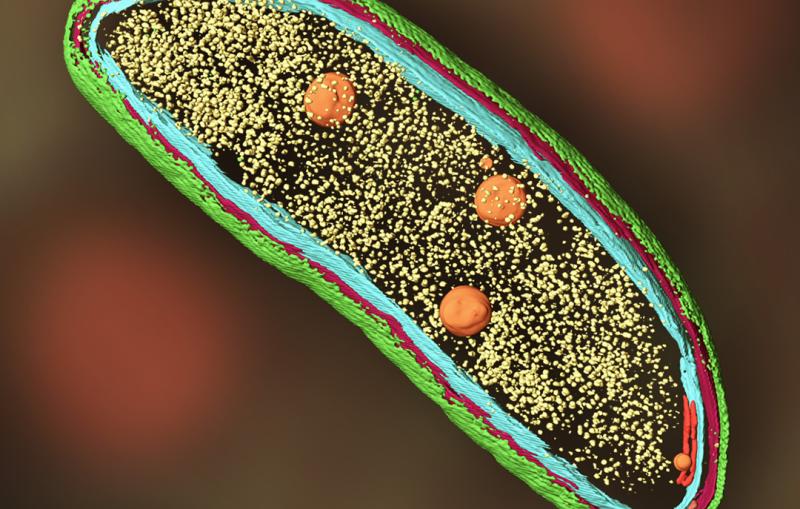

After SARS-CoV-2 infects a cell, the virus hijacks host machinery and starts to produce polyproteins, which are long strands of proteins joined together. But these polyproteins need to be cut into smaller pieces before the virus can infect other people.

To slice polyproteins, the virus calls upon two primary proteases, Mpro and PLpro, which snip protein strings. But these proteases do double duty: they also chomp on other helpful proteins that your immune system needs to communicate.

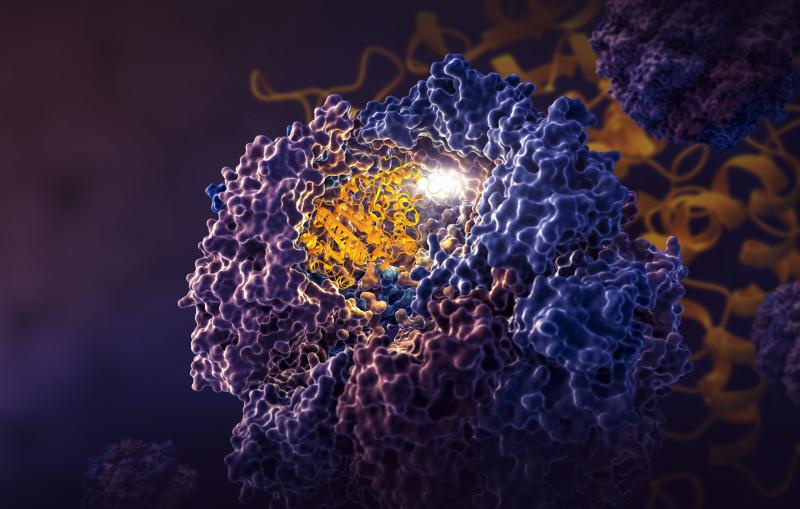

"Currently, we have the antiviral drug, Paxlovid, to stop Mpro, but we don’t have anything to stop PLpro,” said Irimpan Mathews, a lead scientist at SSRL and co-author of the study. “If we develop a drug like Paxlovid that can stop PLpro, we are in really good shape to handle the virus after infection.”

PLpro has been trickier for scientists to pin down because it is highly flexible and has a narrow groove, unlike Mpro. This shape is harder to crystalize, and information from crystal samples is vital in modern medicine design.

"Without a crystal sample, we wouldn’t be able to take a clear picture of PLpro," Pokhrel said. "And if you don’t know what PLpro looks like, it is very hard to create drugs to stop it. You can try to design a drug blindly, but it is much harder than if you know what it looks like," he said.

To grow the crystal, researchers relied on a lot of patience, persistence, and good fortune, said co-senior author Soichi Wakatsuki, professor at SLAC and Stanford.

“Crystallizing the protease and molecule was a real breakthrough in this effort,” Wakatsuki said. “We can now continue to modify the molecule to make it even better at binding to PLpro.”

PLpro’s unique shape also meant that researchers needed a molecule tailored to fit its narrow groove. To create such a molecule, the team started with an existing compound, called GRL0617. Then, they extended the molecule to include a slender portion capped with a chemical group that can react with the protein to form a permanent bond. By considering several extensions, the ORNL researchers transformed the original molecule into a shape that can latch onto PLpro more tightly – and the researchers are still working to improve their design.

“We took an existing compound and modified it to make it bind more strongly to PLpro,” ORNL chemist and lead author Brian Sanders said. “We are now trying to create even better compounds that can be taken as a pill and are more resistant to being broken down in the body.”

Future antiviral design

Although the new molecule slowed PLpro’s protein-cutting activity, researchers still have a few important questions to answer before their results turn into a new antiviral drug. For example, they must make sure that such a drug does not interfere with other, beneficial proteins in our bodies that look similar to PLpro.

“There are many proteins in our body that have similar functions as PLpro, so we have to be careful to avoid blocking those proteins,” said Manat Kaur, a Stanford undergraduate student and intern on the research project. “When you start thinking about this challenge, you realize how many layers of complexity there are in this effort.”

Still, the results made the team more confident that they might be able to design drugs for other viruses in the future, thanks to research processes they developed in studying PLpro. For example, they created an effective collaboration with experts from other DOE national labs and universities to develop the molecule. This collaborative effort could help them apply their strategy – identifying a novel prototype or taking a known prototype molecule, understanding how it binds to a target, and modifying it to make it more effective – to future viruses.

“The molecule we use to attack PLpro might not work on other viruses, but the processes we developed are invaluable,” Pokhrel said. “This approach could be used to help make antiviral drugs to stop the next generation of outbreaks.”

This research was supported by the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a group of Department of Energy national laboratories that was focused on responding to the COVID-19 pandemic with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act, as well as DOE’s Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences and the Office of Biological and Environmental Research. Additional support was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences. SSRL is an Office of Science user facility.

Citation: B. Sanders, S. Pokhrel, et al., Nature Communications, 28 March 2023 (doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37254-w)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.