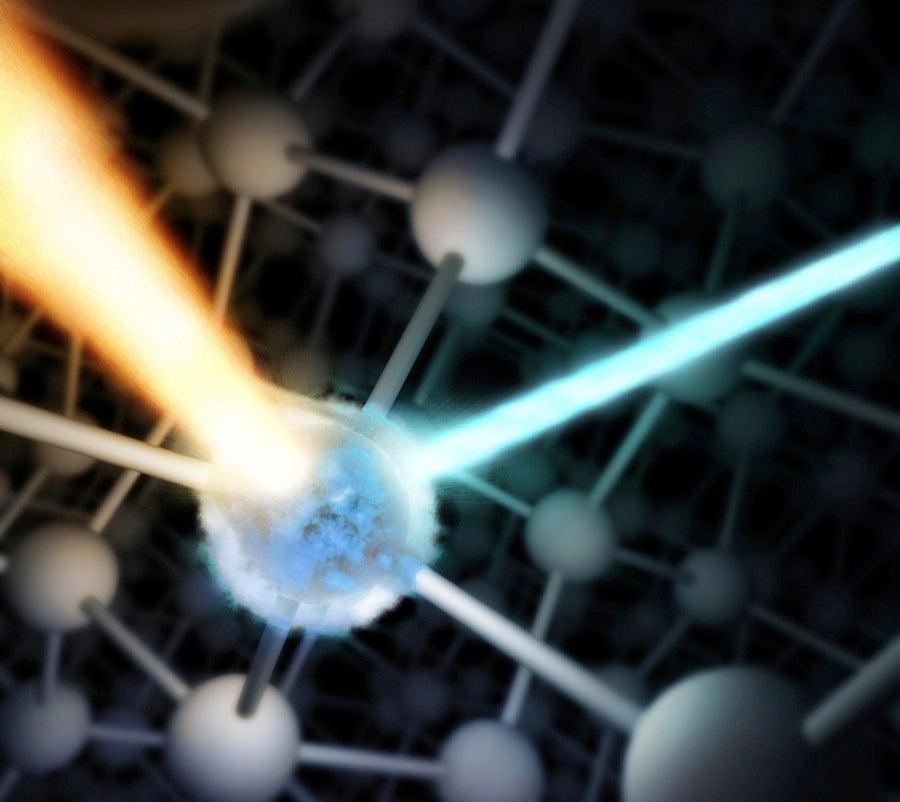

Scientists blast iron with powerful X-rays, then watch its electrons rearrange

A better understanding of how this happens could help researchers hone future electronic measurements and offer insights into how X-rays interact with matter on ultrafast time scales.

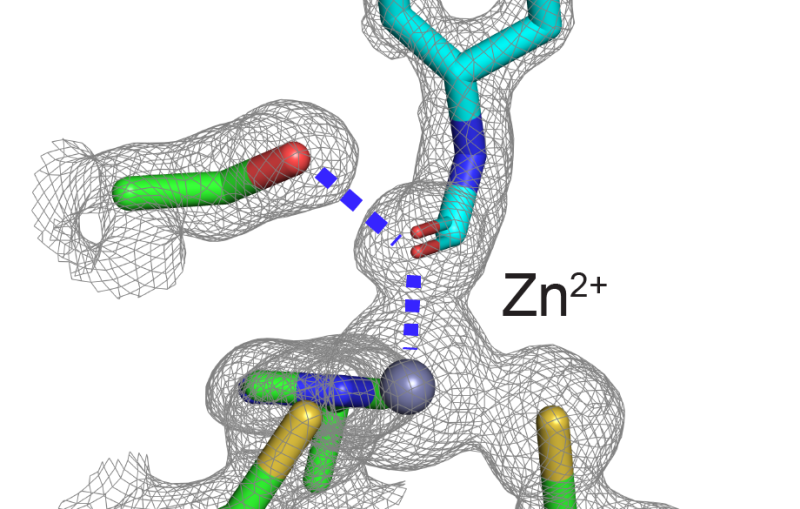

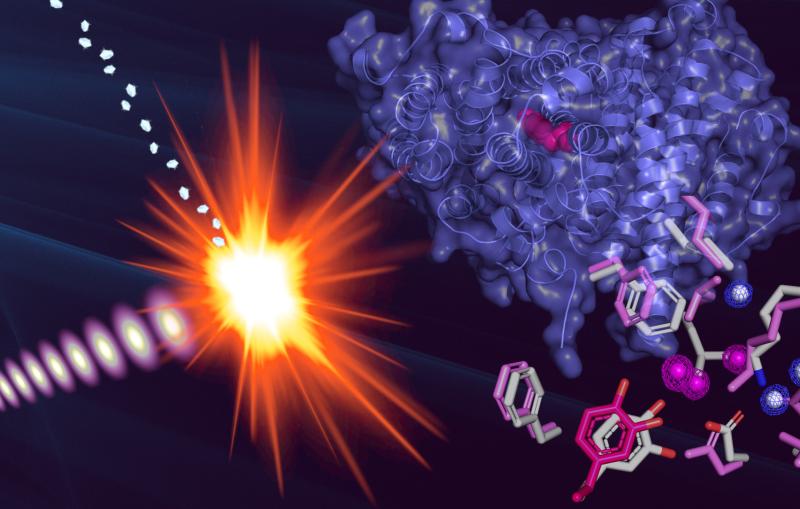

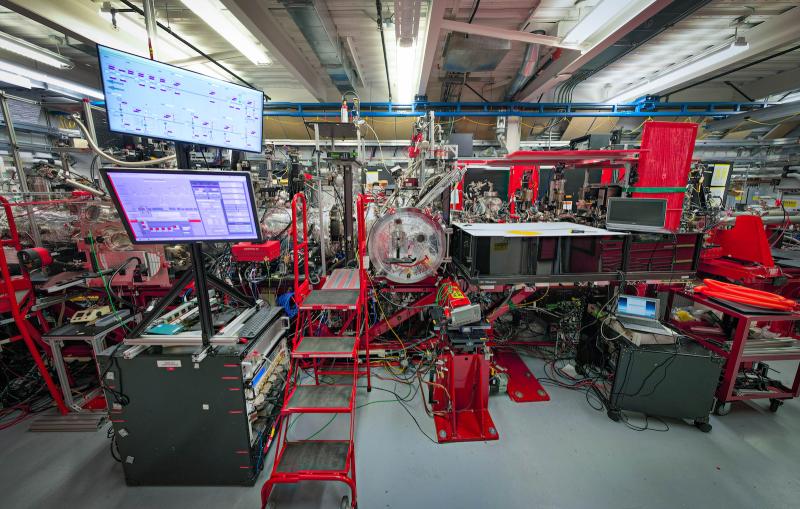

X-ray free-electron lasers, such as the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, produce intense X-ray pulses that allow researchers to image biological objects, such as proteins and other molecular machines, at high resolution. But these powerful beams can destroy delicate samples, triggering changes that can affect the outcome of an experiment and invalidate the results.

To combat this, researchers use a method called probe-before-destroy, which allows them to collect precise information from samples in the instant before they’re blown apart, generating images that preserve information on the molecular structure of biological particles such as cells, proteins and viruses. But until recently, it was unclear how much this method could be trusted for measuring the behavior of electrons, since powerful X-rays can affect electrons much faster than atoms. This could limit the technique’s applicability to ultrafast chemical processes, such as those involved in catalysis.

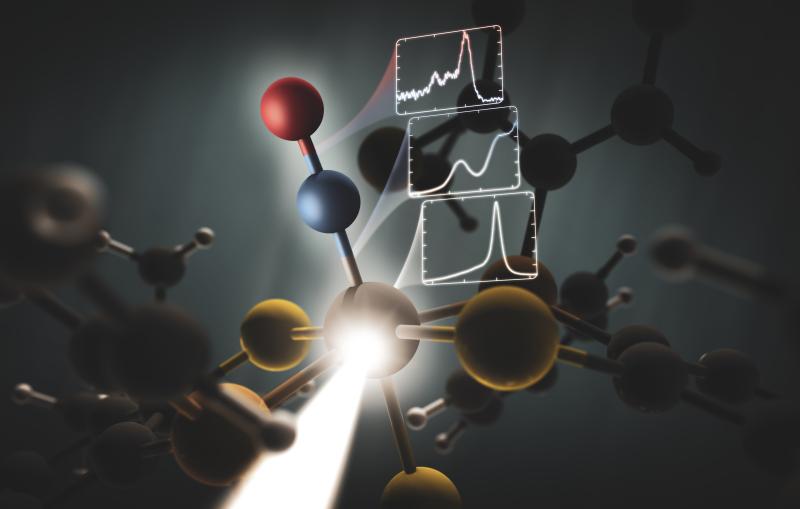

Now, a team led by SLAC scientists Roberto Alonso-Mori, Dimosthenis Sokaras and Diling Zhu has found a way to get a precise idea of how to tune the X-ray beam to make sure electronic structure is not damaged before they measure it, providing higher confidence in the results of XFEL experiments. In a first, the team observed how electrons behaved in the first few femtoseconds, or millionths of a billionth of a second, after an iron sample was blasted with intense laser pulses. Their results, recently published in Scientific Reports, demonstrate how specific properties of the X-ray beam, such as pulse length or intensity, can affect an atom’s outermost electrons, which are the ones that participate in making and breaking bonds during chemical reactions.

The results will allow scientists to fine-tune pump-probe experiments, in which one laser pulse initiates a reaction in a sample and an X-ray pulse immediately measures the rearrangement of the electrons. By varying the time between the laser and the X-ray pulses, researchers can make a series of images and string them into a stop-motion movie of these tiny, fast motions, offering insights into light-activated chemical reactions.

“These experiments are a key tool in our team’s research program,” Sokaras says. “The ability to carefully access the ‘acceptable’ range of LCLS conditions will allow us to perform pump-probe studies that are both reliable and unprecedented.”

The team worked closely with the LCLS accelerator group to deliver even shorter than usual X-ray pulses to study how the electrons rearranged in the first few femtoseconds of the blast. A electron beam streak camera, the XTCAV, was instrumental in precisely measuring the length of the X-ray pulses.

Alonso-Mori says, “The study validates methods that have been used at LCLS in the past few years, settling the debate about whether they are valid or if the data collected is already altered in the first few femtoseconds by the intense X-ray pulses.”

To follow up on this research, the team hopes to probe the electronic structure with even higher intensity, taking advantage of recent progress in shaping and controlling the X-ray beam.

“This can be used to further understand the initial stages of warm dense matter formation processes at XFELs,” says Zhu, “which offer insight into the formation and evolution of planetary systems.”

The research was a collaboration between researchers at LCLS and the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), both DOE Office of Science user facilities. It was supported by the DOE Office of Science.

Citation: R. Alonso-Mori et al., Scientific Reports, 8 October 2020 (10.1038/s41598-020-74003-1)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.