Social Scientist Chooses SLAC as Case Study for Transformation of 'Big Science'

Research Could Lead to Book About Growth of X-ray Science at SLAC

A Swedish social scientist who has been studying the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory for nearly a decade says it represents an ideal case study for how a national lab transforms from a primary mission in particle physics to a much broader mix of research fields.

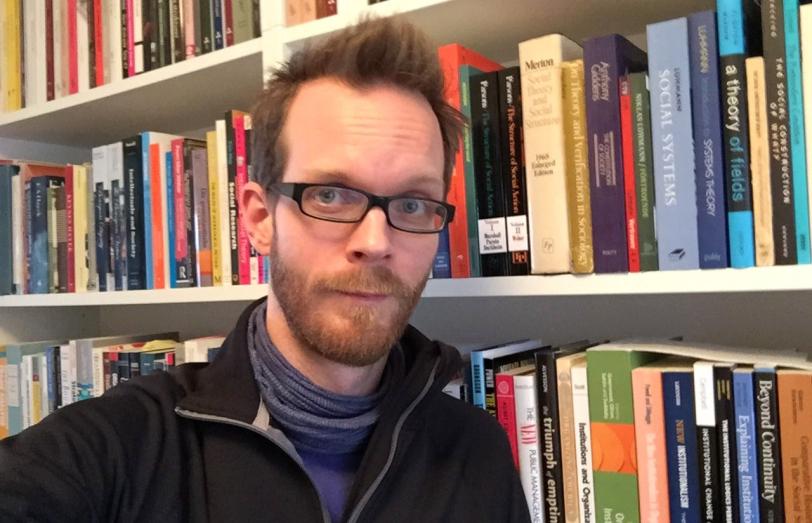

Olof Hallonsten of Lund University specializes in studying the policies and practices of “big science” labs – labs that operate large-scale research facilities. His work highlights the forces that set priorities for Big Science and drive research in new directions, and he plans to eventually publish a book about SLAC that combines material from previous studies.

“The history deserves telling,” Hallonsten said. “There is too little written about SLAC.”

Before his time at SLAC, he participated in a study of a science lab in Sweden and became one of the first to join a PhD program in research policy at his university. "I got so interested in this science that I had hardly heard about before. I was really interested in the politics of the Big Science labs," he said.

Starting in 2007, he visited SLAC several times, interviewing Nobel laureates and past and present SLAC and Stanford administrators and carefully combing through the lab archives.

‘A Full-scale Transformation’

"The more I learned about SLAC, the more it became clear to me that this was one of the most exciting examples of a full-scale transformation," Hallonsten said. "All that glorious history in particle physics – and then it manages to reinvent itself and renew itself.

"Such a transformation cannot just happen by political leadership or by genius scientists making a case for a new direction. It has to be a combination, and I just wanted to learn more about it."

Hallonsten has written book chapters and research papers about other science facilities in the U.S. and abroad, and about parallels in the changing focus of research at SLAC and Germany's DESY lab. Both labs evolved from a particle physics focus into more diverse disciplines, including "photon science," which includes X-ray research and more broadly the interaction of light with matter.

Ingolf Lindau, a native of Sweden who is a professor emeritus at Stanford and SLAC, had helped Hallonsten with his early research and suggested SLAC as a possible study subject.

"Ingolf said, 'You should definitely go to SLAC, because it's such an exciting story,' ” Hallonsten said. “I had nothing against going to California for a couple of months.”

He added, "People were very generous with information. The SLAC archives are absolutely amazing. The staff are really helpful; they have a really good system. For me, as a social scientist, it was like a gold mine."

Witness to a ‘Pivotal’ Period

Looking back on his first visit in 2007, Hallonsten realized he had witnessed a pivotal time in the lab's history, when it was rapidly transitioning away from a primary focus in particle physics.

The lab's premier particle physics project of that era, called BaBar, shut down in 2008 along with the PEP-II ring, which had accelerated electrons and their antiparticles for collisions that would allow scientists to study the imbalance between matter and antimatter that shapes our universe.

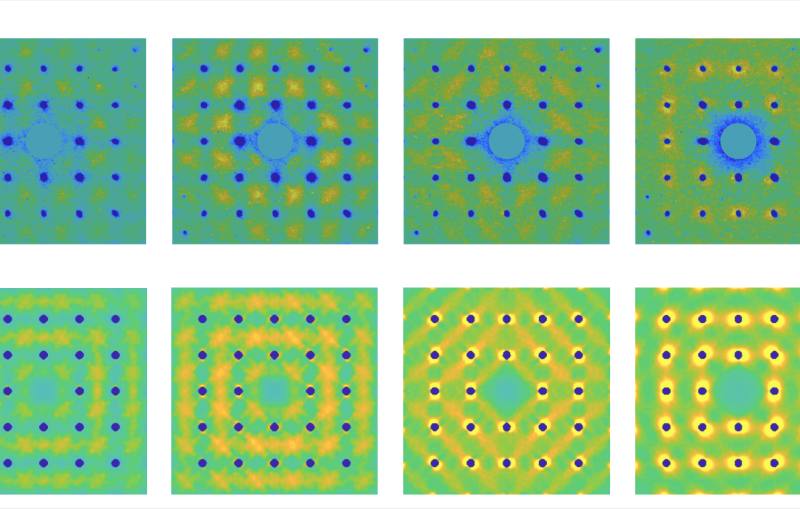

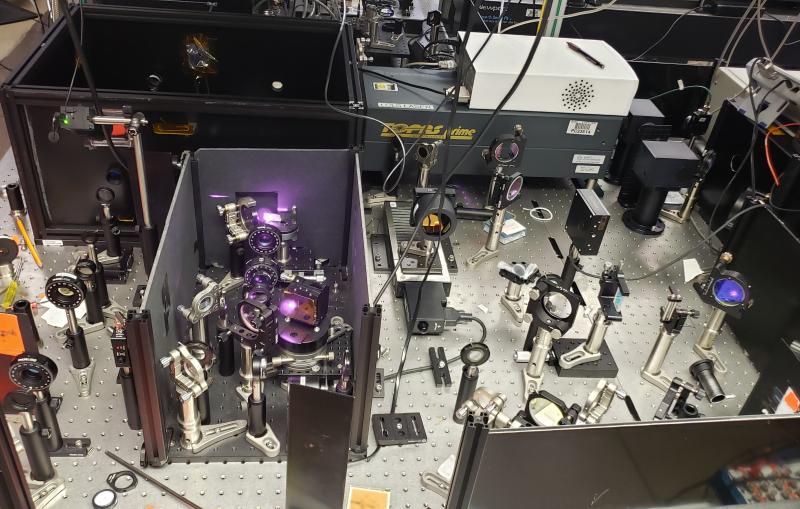

Not far behind was the turn-on of the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser in 2009. It would provide a powerful new source of X-rays to complement and extend the types of experiments that SLAC's first X-ray research facility, now known as the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), had enabled. Both are DOE Office of Science User Facilities.

LCLS, Hallonsten said, began "like a snowball" with preliminary discussions in the early 1990s and then "rose to an avalanche" of support. The launch of LCLS cemented SLAC among the world's premier photon science labs, he said: "LCLS and photon science had become the 'new big thing.'"

Growth of Synchrotron Research at SLAC

One of his major research focuses at SLAC has been the birth and growth of SSRL as a window into larger changes at the lab.

Launched in July 1973 as a Stanford pilot project, by 1974 it became the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Project (SSRP), a National Science Foundation-funded national user facility. It extracted synchrotron radiation – waste X-ray light from an accelerator beam used in particle collider experiments – for research in a wide range of fields.

A DOE user facility since 1982, SSRL now operates 33 experimental stations, drawing more than 1,500 scientists from around the globe each year.

At first these synchrotron radiation experiments were defined as a "parasitic" use that was not allowed to interfere with particle physics experiments, and they were sometimes suspended or greatly curtailed.

But tapping synchrotron radiation as a discovery tool in biology, materials science and other fields became a global trend that "can be thought of as almost a force of nature," Hallonsten said. "It seems like it couldn't be stopped.”

Hallonsten credits concerted and continuing local efforts by SLAC and Stanford administrators and scientists, along with support from national agencies, for finding ways to support and grow synchrotron research at SSRP and then SSRL by changing national and laboratory-level priorities. From its modest beginnings, SSRL developed into an internationally known facility that has contributed to Nobel Prize-winning research.

"It's quite clear to me that it was not by accident that SSRL beat down all those struggles and all those obstacles,” Hallonsten said. “It was by producing good science."

Citations: O. Hallonsten, Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, Winter 2014 (10.1525/hsns.2015.45.2.217)

O. Hallonsten and T. Heinze, Science and Public Policy, 22 March 2013 (10.1093/scipol/sct009)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.