Researchers Watch Protein 'Quake' after Chemical Bond Break

X-ray Laser Experiment Offers New Views into Ultrafast Motions in Life’s Microscopic Machinery

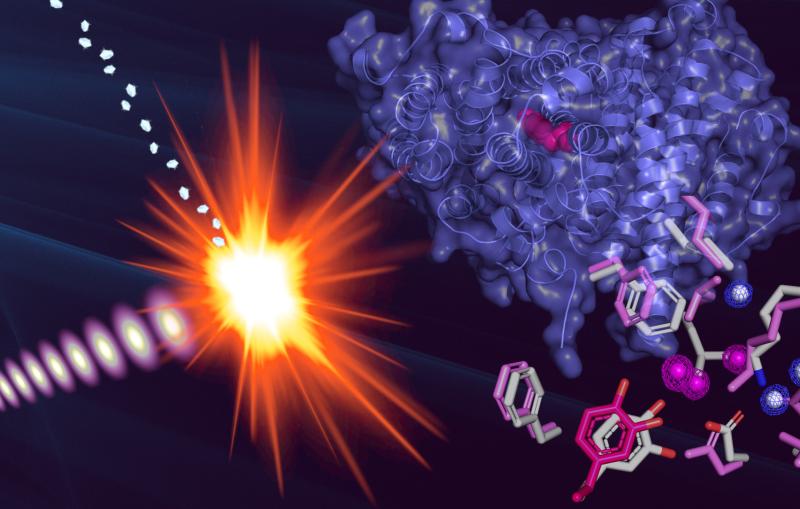

Scientists for the first time have precisely measured a protein’s natural “knee-jerk” reaction to the breaking of a chemical bond – a quaking motion that propagated through the protein at the speed of sound.

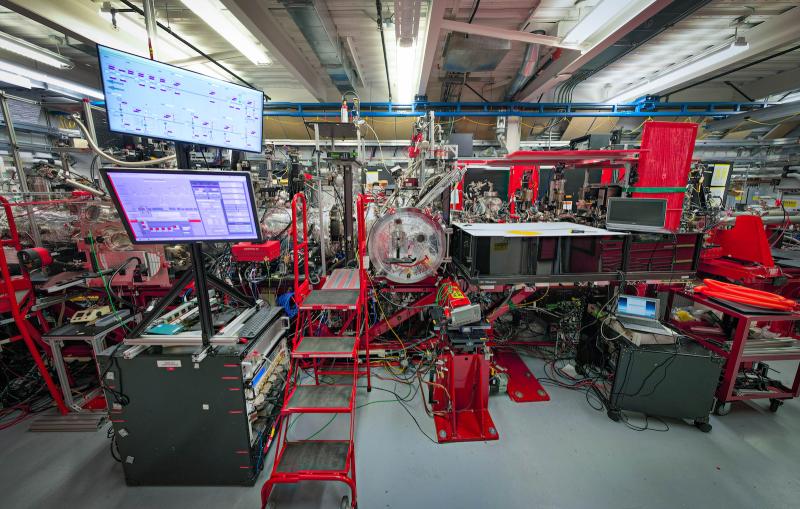

The result, from an X-ray laser experiment at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, could provide clues to how more complex processes unfold as chemical bonds form and break.

“This work helps us to see how proteins work, in general,” said Marco Cammarata, who led the experiment at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser, a DOE Office of Science User Facility. The research is detailed in the April 2 edition of Nature Communications.

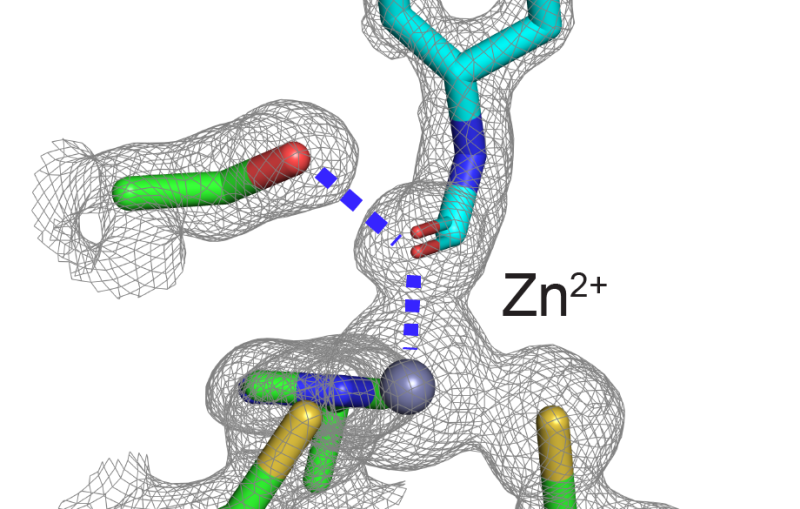

The study focused on myoglobin, a protein that stores oxygen in muscle cells. It is considered a model protein that is sometimes referred to as the “hydrogen atom of biology.” The unique LCLS pulses enabled researches to measure, for the first time at such an ultrafast timescale and under very natural conditions, how the entire protein shook in response to a light-triggered break in a molecular bond.

Proteins are a vital part of the body’s microscopic machinery. Their movement and shape help determine their function, and studying them is key in designing new drugs to fight disease, for example, and in replicating natural systems to produce new fuel sources. Understanding the natural motion of proteins in response to such basic and essential biochemical reactions as bond breaks could provide insight about a range of biological processes.

Watching a ‘Protein Quake’

Scientists had previously seen some evidence of a quaking motion in a bacterial protein jarred by much higher energies, and had also observed myoglobin motion at longer timescales.

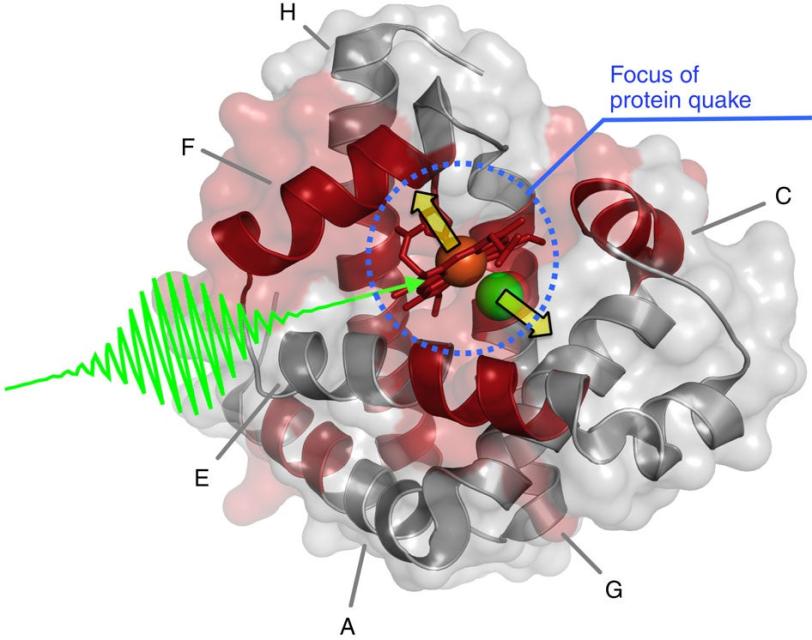

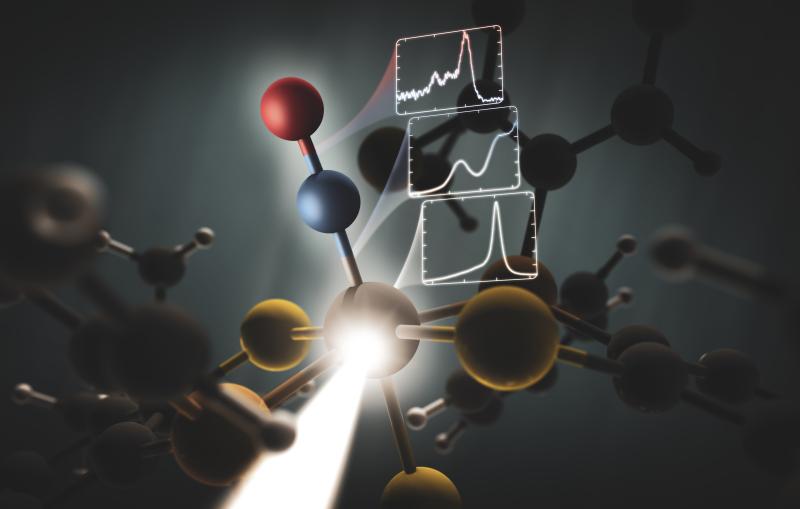

In the LCLS experiment they triggered the quake by attaching carbon monoxide molecules to the myoglobin and then breaking this bond with a light pulse. They then hit the samples with LCLS X-rays, and varied the timing of the X-rays to view the triggered motion.

Within a fraction of a picosecond, or trillionth of a second, after the bond broke, a quake-like wave rolled across the entire protein, causing it to stretch out.

The rapid expansion, which researchers precisely measured from the scattering of ultrabright X-rays that hit the samples, was followed by a vigorous shaking, like rustling leaves on a jounced tree limb.

They found that this quake-like effect, which had its “epicenter” at an iron atom at the core of the protein, dies off after just a few picoseconds. Based on their X-ray observations of the expansion and oscillations, researchers are working on a 3-D model detailing the protein’s motion.

New Clues to Protein Function

The way the protein responds to the shaking motion could provide clues to how myoglobin functions in the body.

“This could suggest how the protein opens up channels to let oxygen in and out,” said Henrik Lemke, an LCLS staff scientist who participated in the experiment. A similar oxygen-release process occurs in photosynthesis.

Cammarata said follow-up experiments, using a combination of X-ray techniques, will help determine whether more complex proteins, including other metal-containing proteins, exhibit the same kind of response as myoglobin.

“We’ll be able to see if this type of quaking is a feature common to other proteins, too,” he said.

Researchers participating in the experiment were from SLAC’s LCLS, University of Palermo in Italy, Institute of Structural Biology and University of Rennes in France, and Institute for Basic Science and KAIST in South Korea. The work was supported by Exploratory Projects Premier Support (PEPS) project “SASLELX” of the CNRS and University of Rennes in France, the University of Palermo in Italy, and the Institute for Basic Science in Korea.

Citation: M. Levantino, et al., Nature Communications, 2 April 2015 (10.1038/ncomms7772)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.