Scientists Invent Self-healing Battery Electrode

Researchers have made the first battery electrode that heals itself, opening a new and potentially commercially viable path for making the next generation of lithium ion batteries for electric cars, cell phones and other devices. National

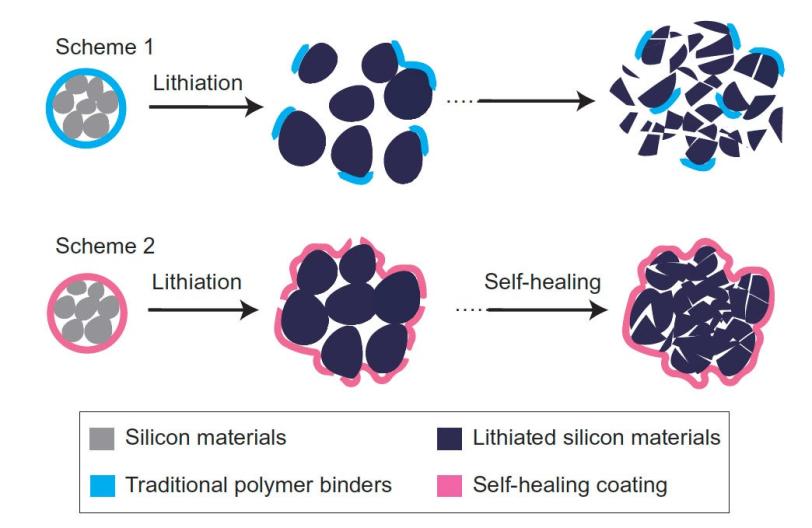

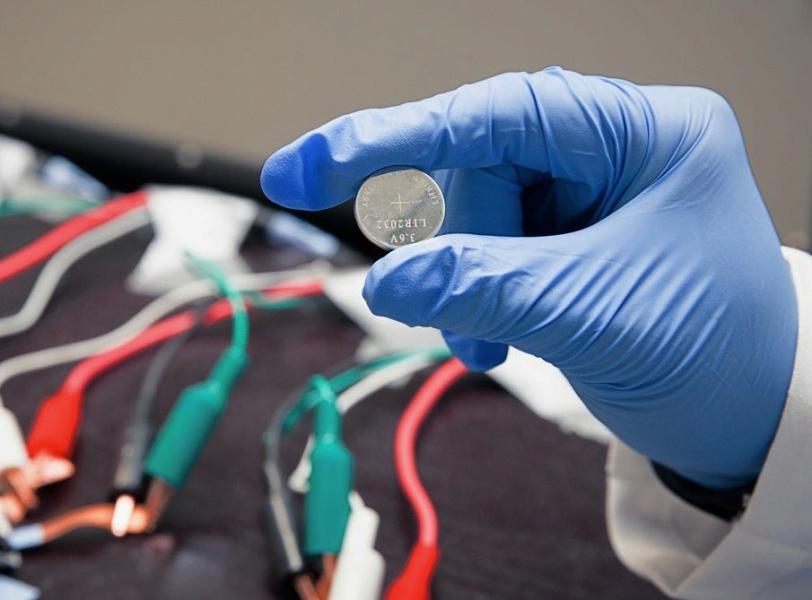

Menlo Park, Calif. — Researchers have made the first battery electrode that heals itself, opening a new and potentially commercially viable path for making the next generation of lithium ion batteries for electric cars, cell phones and other devices. The secret is a stretchy polymer that coats the electrode, binds it together and spontaneously heals tiny cracks that develop during battery operation, said the team from Stanford University and the Department of Energy’s (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

They report the advance in the Nov. 19 issue of Nature Chemistry.

“Self-healing is very important for the survival and long lifetimes of animals and plants,” said Chao Wang, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford and one of two principal authors of the paper. “We want to incorporate this feature into lithium ion batteries so they will have a long lifetime as well.”

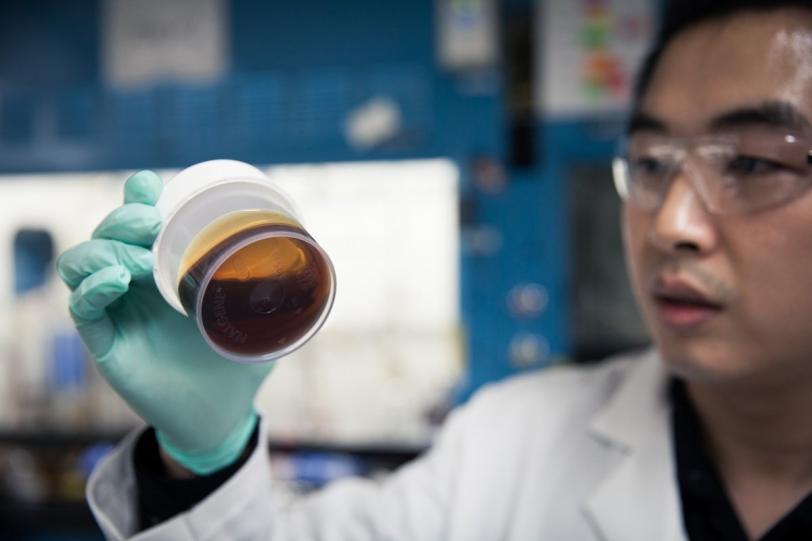

Chao developed the self-healing polymer in the lab of Stanford Professor Zhenan Bao, whose group has been working on flexible electronic skin for use in robots, sensors, prosthetic limbs and other applications. For the battery project he added tiny nanoparticles of carbon to the polymer so it would conduct electricity.

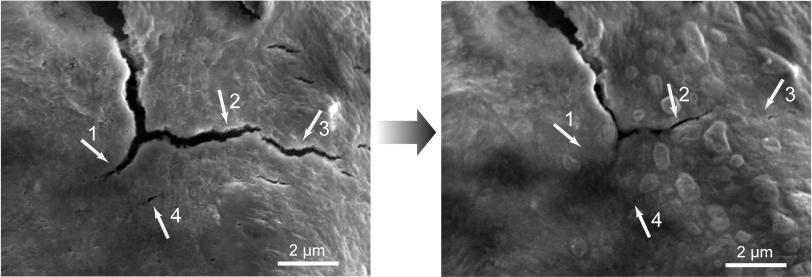

”We found that silicon electrodes lasted 10 times longer when coated with the self-healing polymer, which repaired any cracks within just a few hours,” Bao said.

“Their capacity for storing energy is in the practical range now, but we would certainly like to push that,” said Yi Cui, an associate professor at SLAC and Stanford who led the research with Bao. The electrodes worked for about 100 charge-discharge cycles without significantly losing their energy storage capacity. “That’s still quite a way from the goal of about 500 cycles for cell phones and 3,000 cycles for an electric vehicle,” Cui said, “but the promise is there, and from all our data it looks like it’s working.”

Researchers worldwide are racing to find ways to store more energy in the negative electrodes of lithium ion batteries to achieve higher performance while reducing weight. One of the most promising electrode materials is silicon; it has a high capacity for soaking up lithium ions from the battery fluid during charging and then releasing them when the battery is put to work.

But this high capacity comes at a price: Silicon electrodes swell to three times normal size and shrink back down again each time the battery charges and discharges, and the brittle material soon cracks and falls apart, degrading battery performance. This is a problem for all electrodes in high-capacity batteries, said Hui Wu, a former Stanford postdoc who is now a faculty member at Tsinghua University in Beijing, the other principal author of the paper.

To make the self-healing coating, scientists deliberately weakened some of the chemical bonds within polymers – long, chain-like molecules with many identical units. The resulting material breaks easily, but the broken ends are chemically drawn to each other and quickly link up again, mimicking the process that allows biological molecules such as DNA to assemble, rearrange and break down.

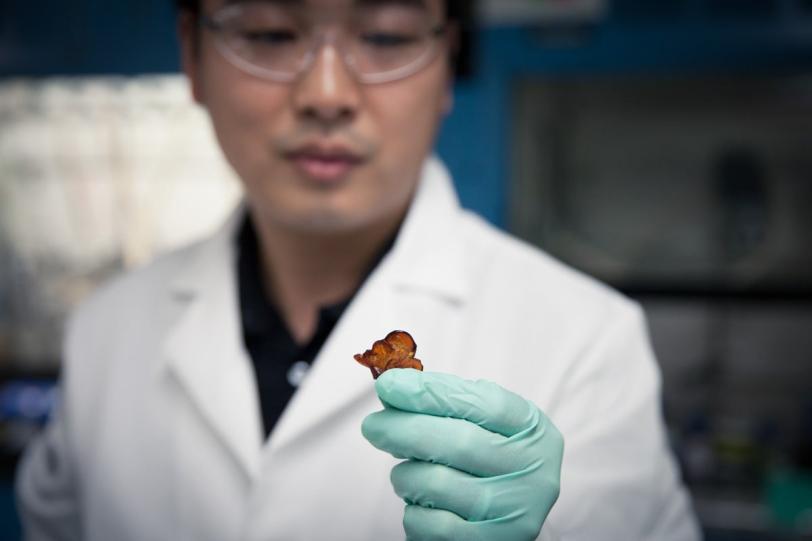

Balloon Coated with Self-Healing Polymer

To show how flexible their self-healing polymer is, researchers coated a balloon with it and then inflated and deflated the balloon repeatedly, mimicking the swelling and shrinking of a silicon electrode during battery operation. The polymer stretches but does not crack. (Brad Plummer/SLAC)

Researchers in Cui’s lab and elsewhere have tested a number of ways to keep silicon electrodes intact and improve their performance. Some are being explored for commercial uses, but many involve exotic materials and fabrication techniques that are challenging to scale up for production.

The self-healing electrode, which is made from silicon microparticles that are widely used in the semiconductor and solar cell industries, is the first solution that seems to offer a practical road forward, Cui said. The researchers said they think this approach could work for other electrode materials as well, and they will continue to refine the technique to improve the silicon electrode’s performance and longevity.

The research team also included Zheng Chen and Matthew T. McDowell of Stanford. Cui and Bao are members of the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences, a joint SLAC/Stanford institute. The research was funded by DOE through SLAC’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program and by the Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford University.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

The Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) is a joint institute of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. SIMES studies the nature, properties and synthesis of complex and novel materials in the effort to create clean, renewable energy technologies. For more information, please visit simes.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Citation: C. Wang et al., Nature Chemistry, 17 November 2013 (10.1038/nchem.1802)

Press Office Contact:

Andy Freeberg, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: afreeberg@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-4359

Scientist Contacts:

Yi Cui, SLAC / Stanford University: yicui@stanford.edu, (650) 723-4613

Zhenan Bao, SLAC / Stanford University: zbao@stanford.edu, (650) 723-2419

Also on the Web:

The Zhenan Bao Research Group home page

The Yi Cui Lab home page

The Stanford Institute for Materials & Energy Sciences (SIMES) home page