New Analysis Shows How Proteins Shift Into Working Mode

In an advance that will help scientists design and engineer proteins, a team including researchers from SLAC and Stanford has found a way to identify how protein molecules flex into specific atomic arrangements required to catalyze chemical reactions essential for life.

By Mike Ross

In an advance that will help scientists design and engineer proteins, a team including researchers from SLAC and Stanford has found a way to identify how protein molecules flex into specific atomic arrangements required to catalyze chemical reactions essential for life.

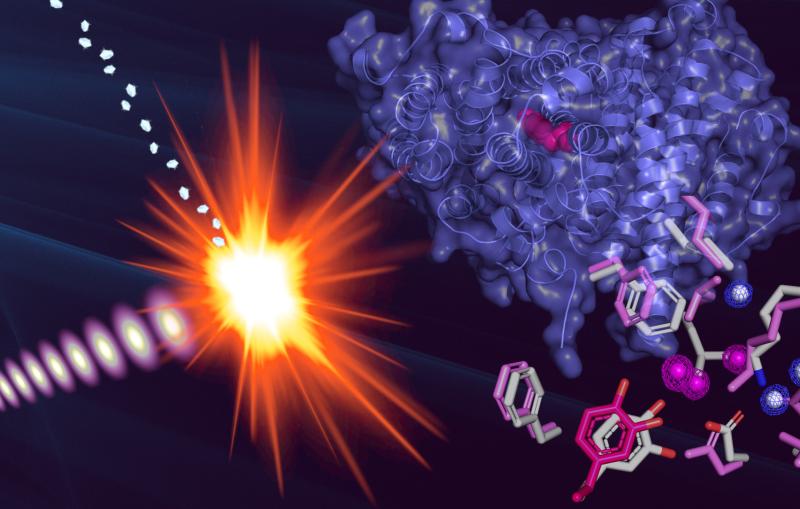

The achievement, published Sunday (Aug. 4, 2013) in Nature Methods, uses a new computer algorithm to analyze data from X-ray studies of crystallized proteins. Scientists were able to identify cascades of atomic adjustments that shift protein molecules into new shapes, or conformations.

"Proteins need to move around to do their part in keeping the organism alive," said Henry van den Bedem, first author on the paper and a researcher with the Structure Determination Core of the Joint Center for Structural Genomics (JCSG) at the SSRL Directorate of SLAC. "But often these movements are very subtle and difficult to discern. Our research is aimed at identifying those fluctuations from X-ray data and linking them to a protein's biological functions. Our work provides important new insights, which will eventually allow us to re-engineer these molecular machines."

Protein primer

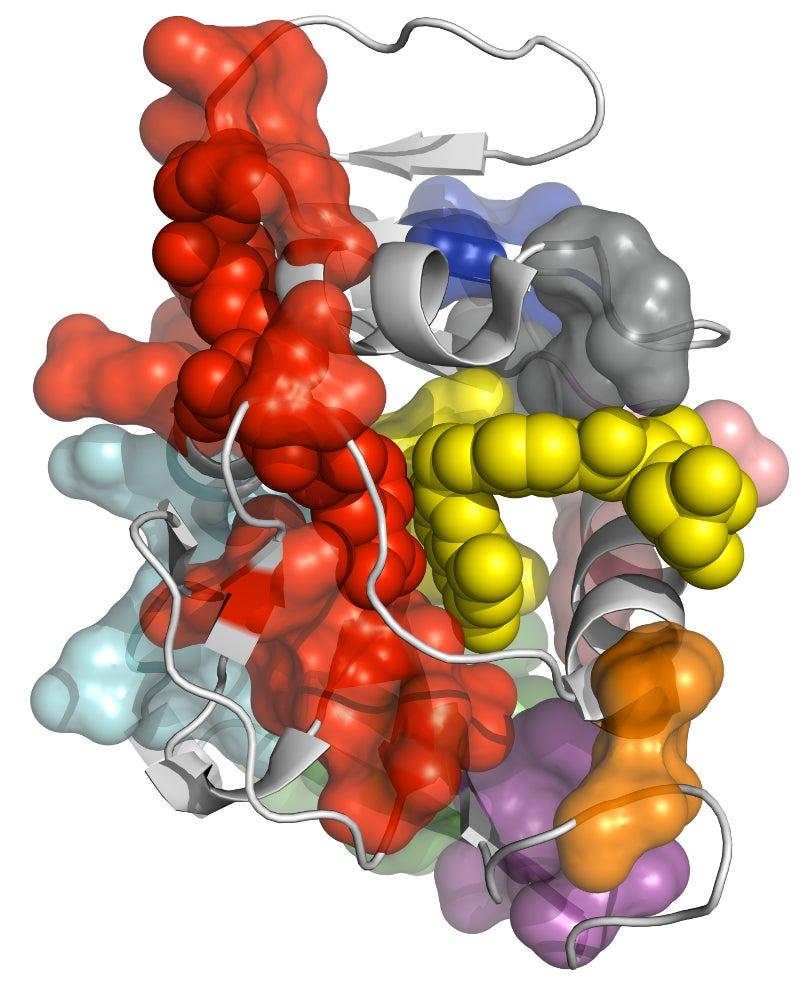

Proteins are large molecules composed of a large number of up to 20 different amino acid units linked into chains, branches and loops. In living organisms, each protein typically adopts many different conformations, with each one exposing a specific section of the molecule and making it available for chemical activity. Changing the protein’s atomic structure through genetic mutations, for instance, can interfere with critical chemical reactions, leading to disease or even death. On the other hand, drugs are often designed to promote or block certain protein fluctuations, so understanding the exact mechanism behind the fluctuations is very important.

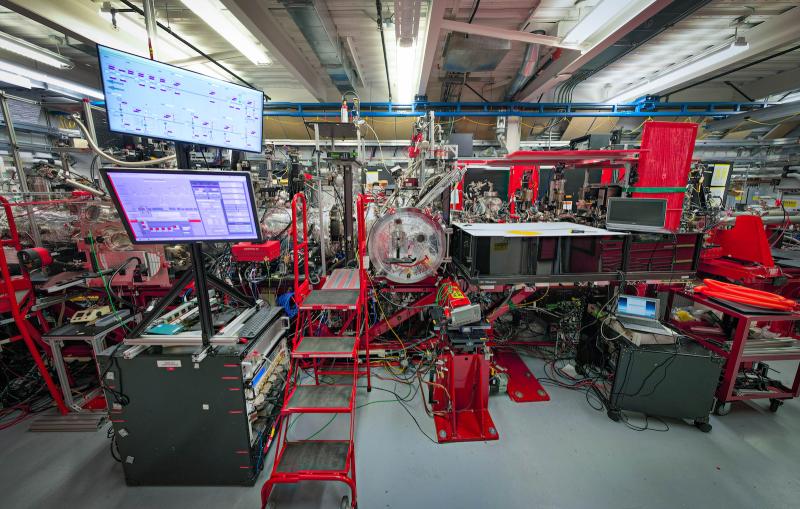

For more than 50 years, scientists around the world have combined experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging with computer algorithms to determine the three-dimensional structure of proteins.

Each experimental technique has its strengths and limitations.

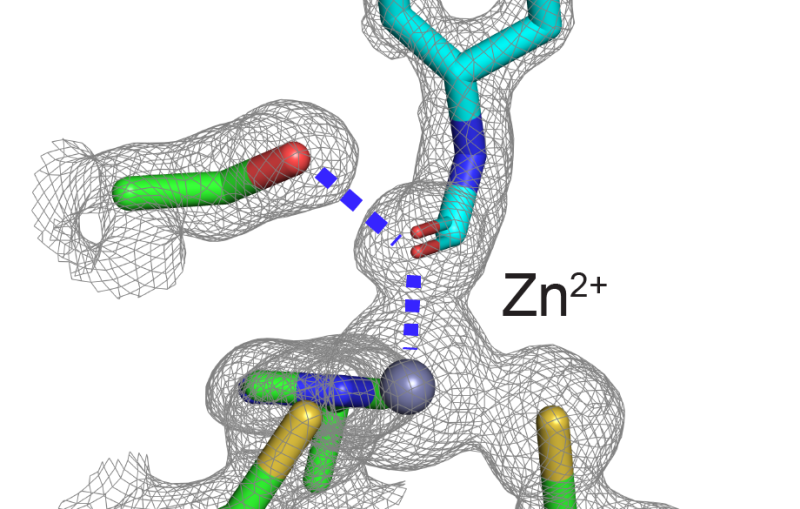

X-ray crystallography pinpoints the precise locations of atoms within the molecule, typically at extremely low temperatures, and it yields a static picture of the naturally floppy protein molecule. It doesn’t show the many important conformations the molecule adopts when immersed in the warm, liquid environment of a living organism.

New Analysis Shows How Proteins Shift Into Working Mode

Nuclear magnetic resonance reveals the bonding patterns of a protein operating in a liquid environment at room temperature, but averages all of its conformations rather than providing details about each one.

The new technique combines the best of both worlds. Based on X-ray data collected at room temperature, scientists identified regions where cascades of conformational changes take place, and confirmed that those same regions can be found independently in NMR data.

New computer algorithm

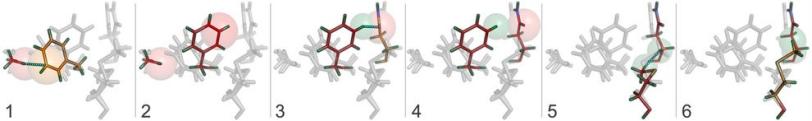

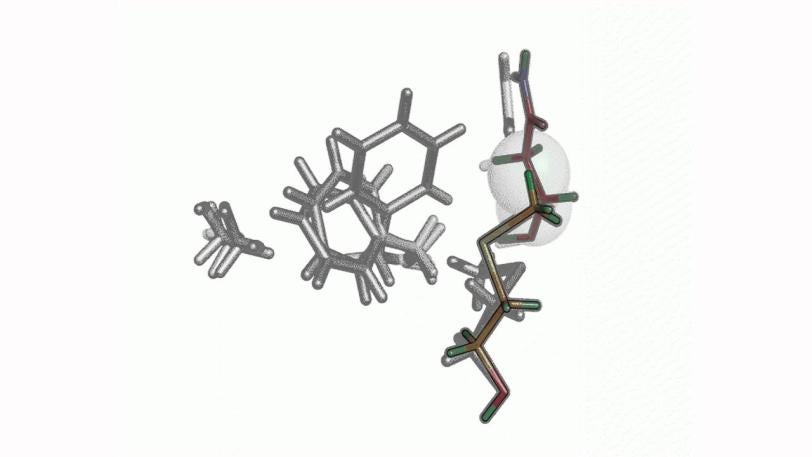

Central to the new technique is a new computer algorithm, called CONTACT, that analyzes protein structures determined by room temperature X-ray crystallography. Built upon an earlier algorithm created by van den Bedem, CONTACT detects how subtle features in the experimental data produced by changing conformations propagate through the protein and identifies regions within the protein where these cascades of small changes are likely to result in stable conformations.

The researchers tested CONTACT on two enzymes – proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. One, cyclophilin A, can facilitate protein folding, while the other, dihydrofolate reductase (dhfr), helps regulate cell proliferation and cell growth. Their method, for the first time, provides an atomically detailed structural framework for the dhfr NMR measurements, thus bridging the traditional divide between static, single X-ray and dynamic, averaged NMR structures.

The research team also included scientists from University of California-San Francisco and The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla.

The ongoing research, in collaboration with additional research groups, is aimed at applying CONTACT to a wider range of proteins. Additionally, the team will create new features to make CONTACT more accurate by adding sensitivity to electrostatic and water-related interactions.

The Joint Center for Structural Genomics is a multi-institutional consortium funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences as part of the Protein Structure Initiative of the National Institutes of Health.