Experiment Finds Ulcer Bug's Achilles' Heel

X-rays Pinpoint Drug Target for Bacteria that Affect Hundreds of Millions Worldwide

Menlo Park, Calif. — Experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have revealed a potential new way to attack common stomach bacteria that cause ulcers and significantly increase the odds of developing stomach cancer.

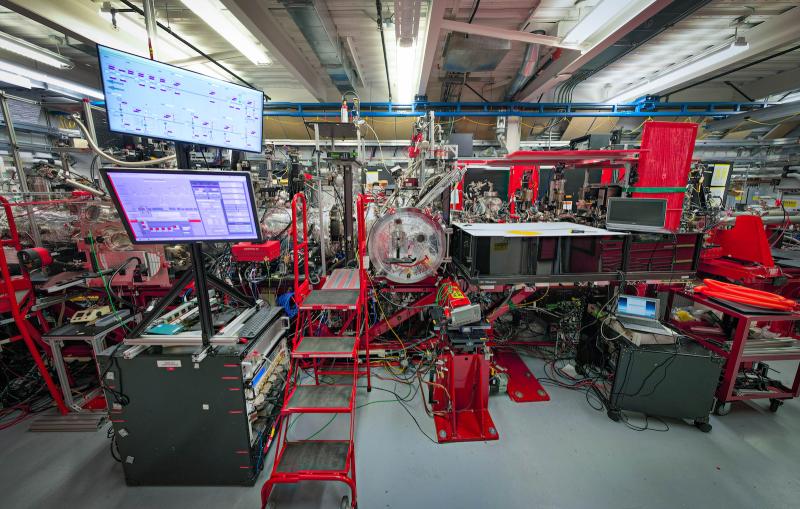

The breakthrough, made using powerful X-rays from SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), was the culmination of five years of research into the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which is so tough it can live in strong stomach acid. At least half the world's population carries H. pylori and hundreds of millions suffer health problems as a result; current treatments require a complicated regimen of stomach-acid inhibitors and antibiotics.

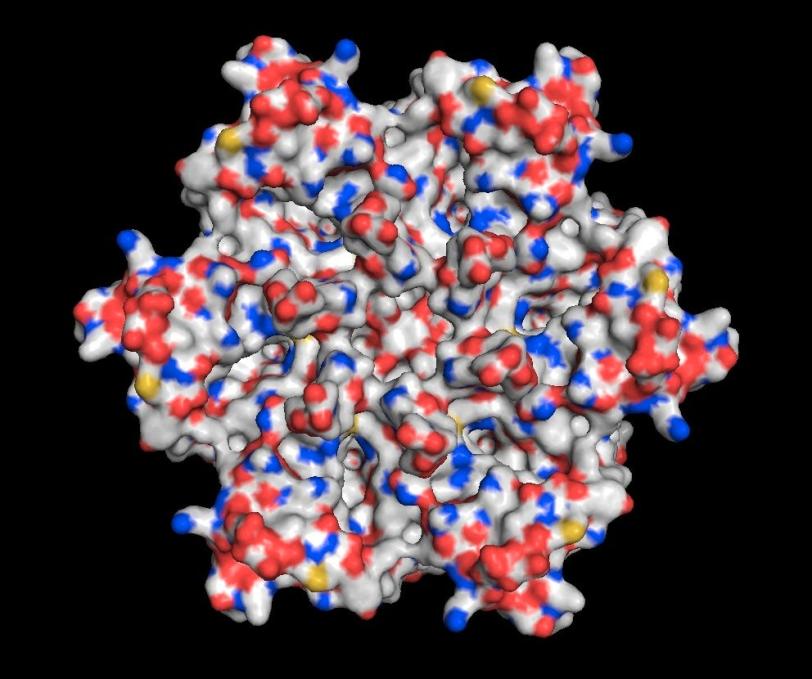

"We were looking for a means to disrupt H. pylori's own mechanism for protecting itself against stomach acid," said Hartmut "Hudel" Luecke, a researcher at the University of California, Irvine, and principal investigator on the paper, published online Dec. 9 in Nature. With this study, he said, "We have deciphered the three-dimensional molecular structure of a very promising drug target."

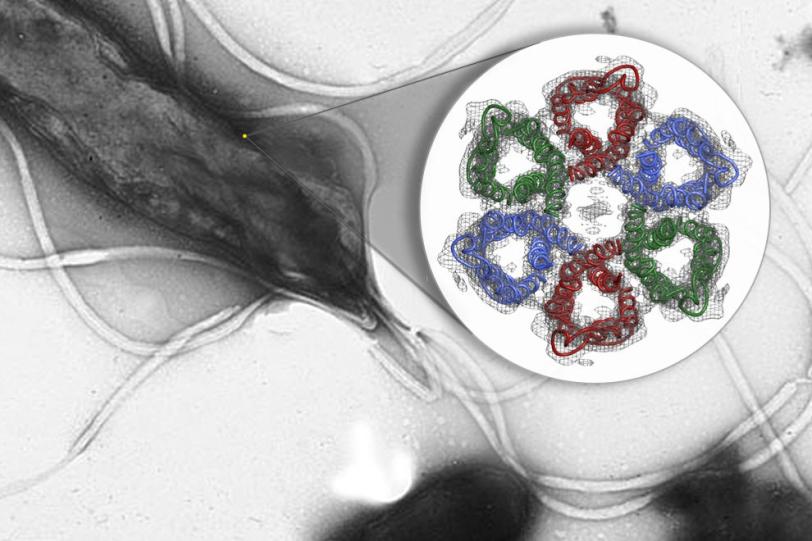

Luecke and his team zeroed in on tiny channels that H. pylori uses to allow in urea from gastric juice in the stomach; it then breaks this compound into ammonia, which neutralizes stomach acid. Blocking the channels would disable this protective system, leading to a new treatment for people with the infection.

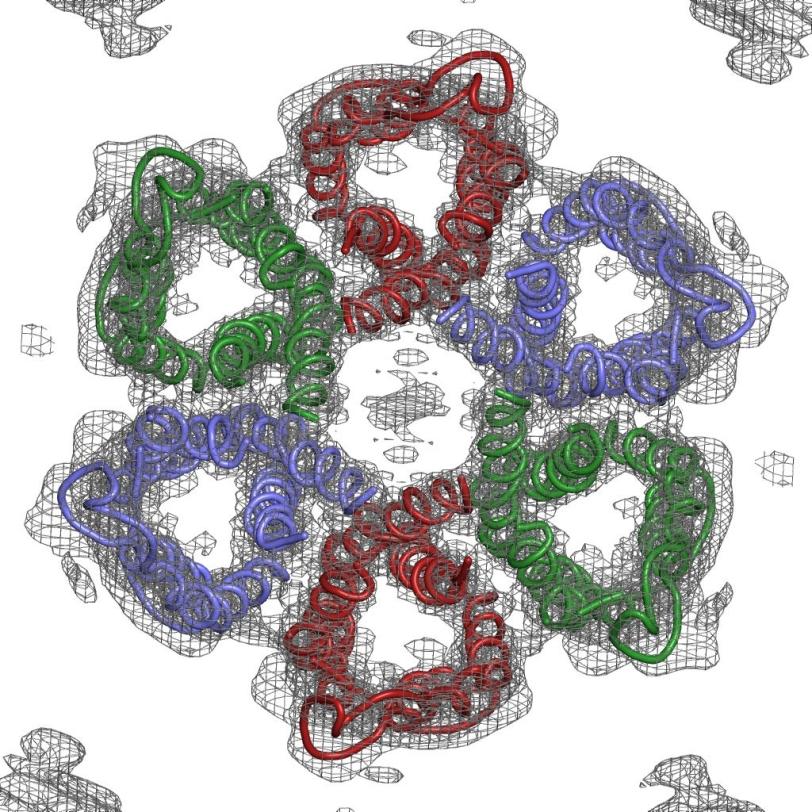

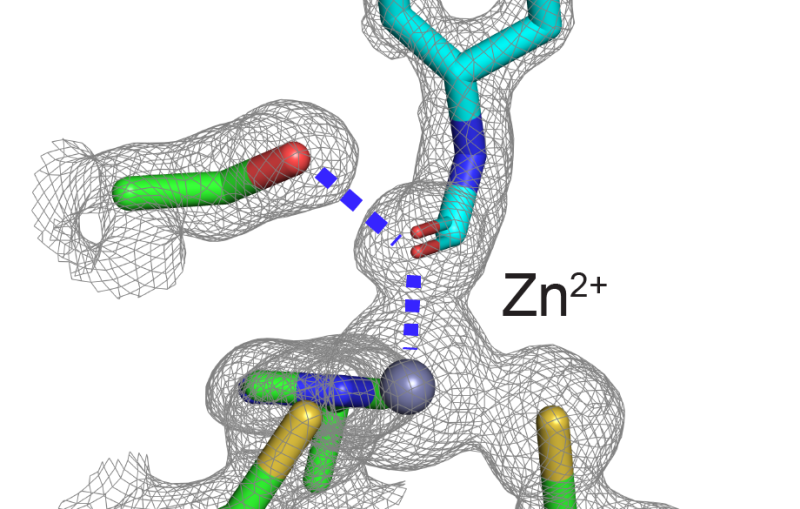

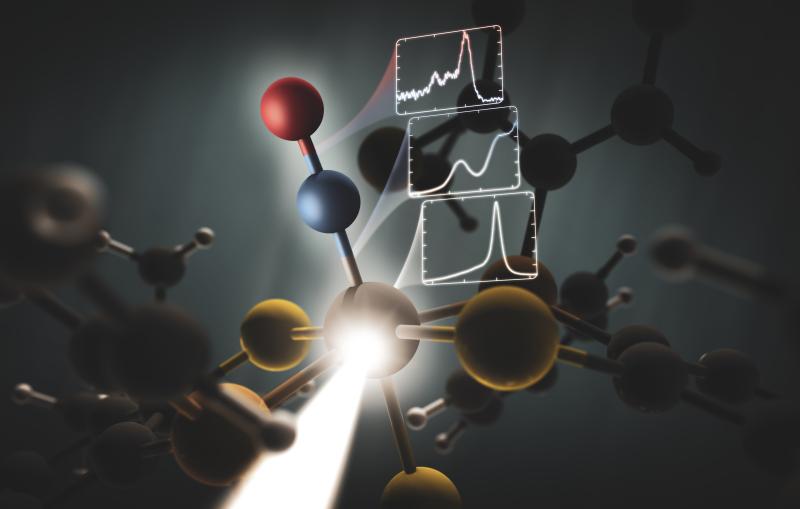

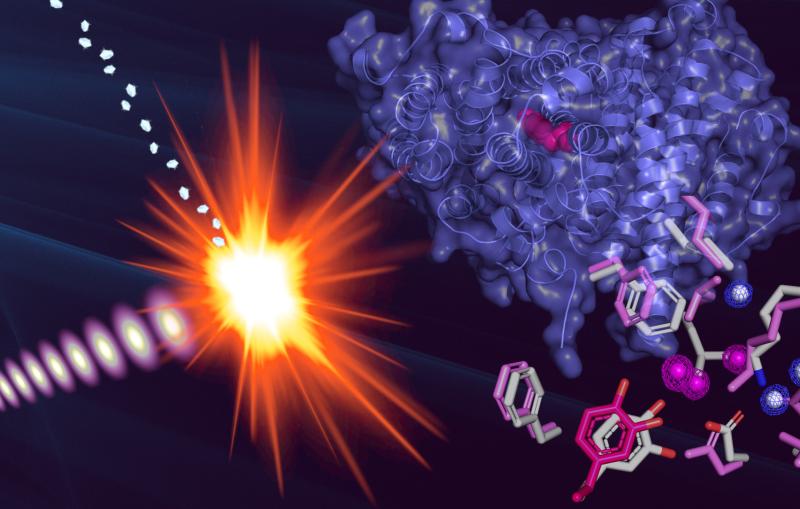

Solving the structure of the protein to find the specific area to target wasn't easy. The channels are formed by the protein embedded in the bacterium's cell membrane, and membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to crystallize, which is a prerequisite for using protein crystallography, the main technique for determining protein structures. This technique bounces X-rays off of the electrons in the crystallized protein to generate the experimental data used to build a 3-D map showing how the protein's atoms are arranged.

The challenge with membrane proteins is that they are especially hard to grow good quality crystals of, and for this experiment, said Luecke, "We needed to grow and screen thousands of crystals."

"We collected over 100 separate data sets and tried numerous structural determination techniques," said Mike Soltis, head of SSRL's Structural Molecular Biology division, who worked with Luecke and his team to create the 3-D map of the atomic structure. The final data set was measured at SSRL's highest brightness beam line (12-2), which produced the critical data that met the challenge.

"This is the hardest structure I've ever deciphered, and I've been doing this since 1984," Luecke said. "You have to try all kinds of tricks, and these crystals fought us every step of the way. But now that we have the structure, we've reached the exciting part—the prospect of creating specific, safe and effective ways to target this pathogen and wipe it out."

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the UC Irvine Center for Biomembrane Systems and the US Veterans Administration. SSRL is supported by DOE's Office of Science, and the SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program by DOE and NIH. The research team also included scientists from the University of California, Los Angeles (Greater West Los Angeles Health Care System).

The research paper is available online from Nature: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nature11684.html

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Scientist Contact:

Hartmut Luecke, Center for Biomembrane Systems, UC Irvine: hudel@uci.edu, +1 949 394 7574

Press Office Contact:

Andy Freeberg, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: afreeberg@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-4359

UC Irvine)