Study Provides Recipe for 'Supercharging' Atoms with X-ray Laser

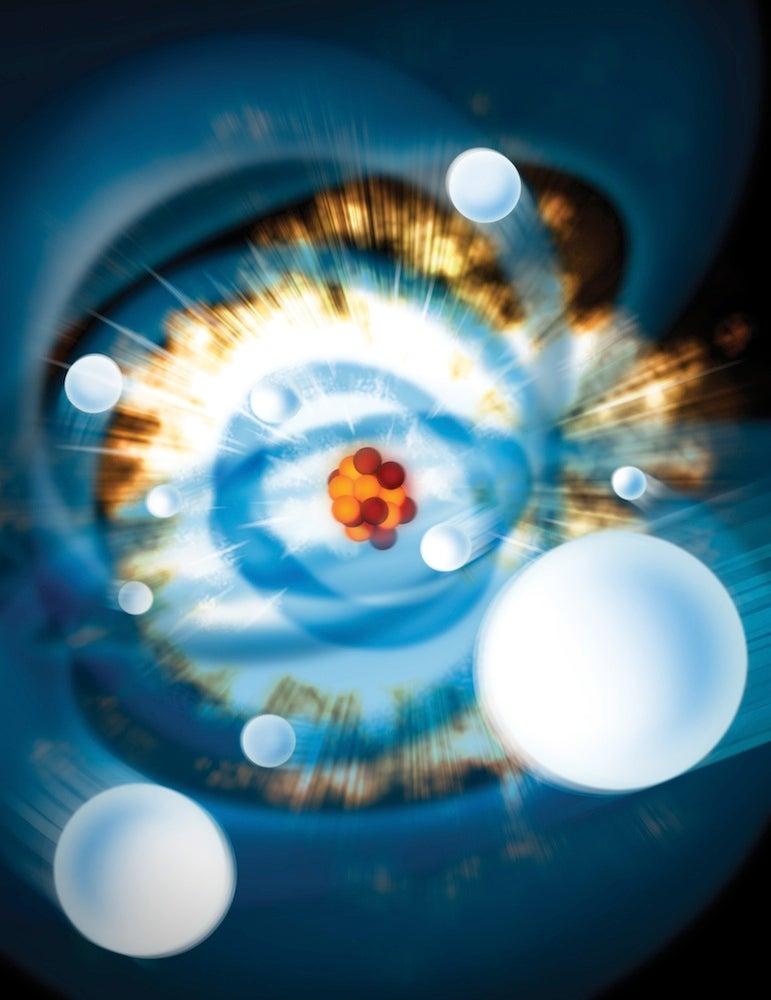

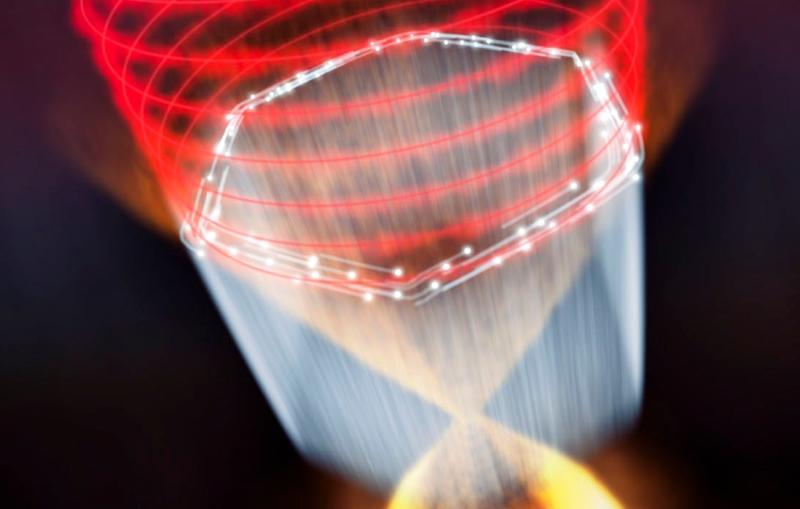

Menlo Park, Calif. — Researchers using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have found a way to strip most of the electrons from xenon atoms, creating a “supercharged,” strongly positive state at energies previously thought too low.

Menlo Park, Calif. — Researchers using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have found a way to strip most of the electrons from xenon atoms, creating a “supercharged,” strongly positive state at energies previously thought too low.

The findings, which defy expectations and theory, could help scientists deliberately induce the high levels of damage needed to study extreme states of matter or ward off damage in samples they’re trying to image. The results were reported this week in Nature Photonics.

While the powerful X-rays of LCLS inevitably destroy the samples being studied, delaying damage – even for millionths of billionths of a second – can prove critical in producing detailed images and other data.

"Our results give a 'recipe' for maximizing the loss of electrons in a sample,” said Daniel Rolles, a researcher for the Max Planck Advanced Study Group at the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science in Hamburg, Germany, who led the experiments. “For instance, researchers can use our findings if they’re interested in creating a very highly charged plasma. Or, if the supercharged state isn’t part of the study, they can use our findings to know what X-ray energies to avoid."

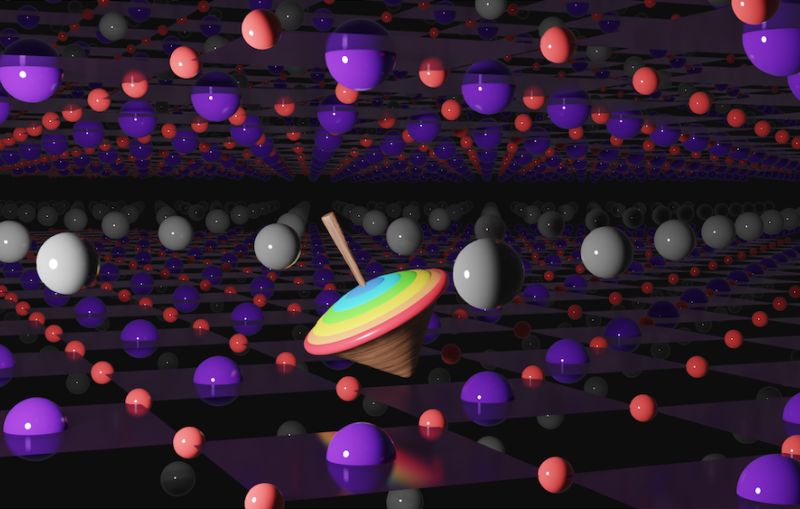

Just as a stretched guitar string can vibrate and sustain a note, a specific tuning of the laser's properties can cause atoms and molecules to resonate. The resonance excites the atoms and causes them to shake off electrons at a rate that otherwise would require higher energies.

While it is common knowledge that triggering resonances in atoms will affect their charged states, "it was not clear to anybody what a dramatic effect this could have in heavy atoms when they are being ionized by a source like LCLS," Rolles said. "It was the highest charge state ever observed with a single X-ray pulse, which shows that the existing theoretical approaches have to be modified."

The team had previously used a laser facility in Germany to expose various atoms and molecules to pulses of ultraviolet light, and was eager to use the higher-energy LCLS for further studies.

“The LCLS experiment pushed the charged state to an unprecedented and unexpected extreme – more than doubling the expected energy absorbed per atom and ejecting dozens of electrons,” said Benedikt Rudek from the Max Planck Advanced Study Group, who analyzed the data.

In addition to creating or avoiding supercharged plasma states in experiments, Rolles said the "dramatic change" caused by resonance in the absorption of X-ray energy could someday be exploited to improve the resolution of images captured in LCLS experiments.

"Most biological samples have some heavy atoms embedded, for instance," Rolles said, and in some experiments, avoiding the resonance trigger might prevent rapid damage to those atoms.

The researchers have since done similar LCLS experiments involving the heavy element krypton and molecular systems that contain other heavy atoms, said Artem Rudenko of Kansas State University, who led a recent follow-up experiment.

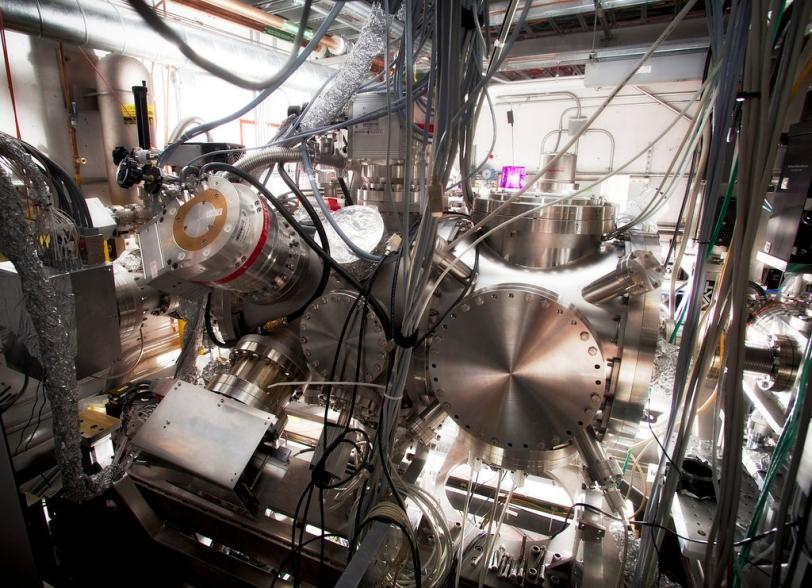

The team's precise measurements were made possible by a sophisticated experimental station built by the Max Planck Advanced Study Group in Germany. In total, the equipment weighed about 11 tons and was shipped to SLAC in 40 crates. It stayed at LCLS for three years and was used in more than 20 experiments ranging from atomic and molecular physics to material sciences and bio-imaging.

"Reassembling this machine at LCLS within one month and then commissioning it and doing a science experiment in only seven days was an absolutely incredible feat," said Rolles.

The research team included scientists from 19 research centers, including: Max Planck Advanced Study Group and several Max Planck institutes, PNSensor GmbH, Technical University of Berlin, Jülich Research Center, University of Hamburg and Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt in Germany; SLAC and Western Michigan and Kansas State universities in the U.S.; University of Pierre and Marie Curie and National Center for Scientific Research in France; and Kyoto and Tohoku universities in Japan.

LCLS is supported by DOE’s Office of Science.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

The research paper is available online from Nature Photonics: http://www.nature.com/nphoton/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nphoton.2012.261.html

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.