SSRL Confirms Anti-Flu Proteins Work as Designed

Understanding why proteins interact with certain specific molecules and not with the myriad others in their environment is a major goal of molecular biology.

By Lori Ann White

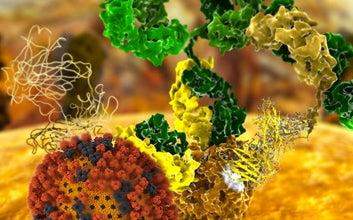

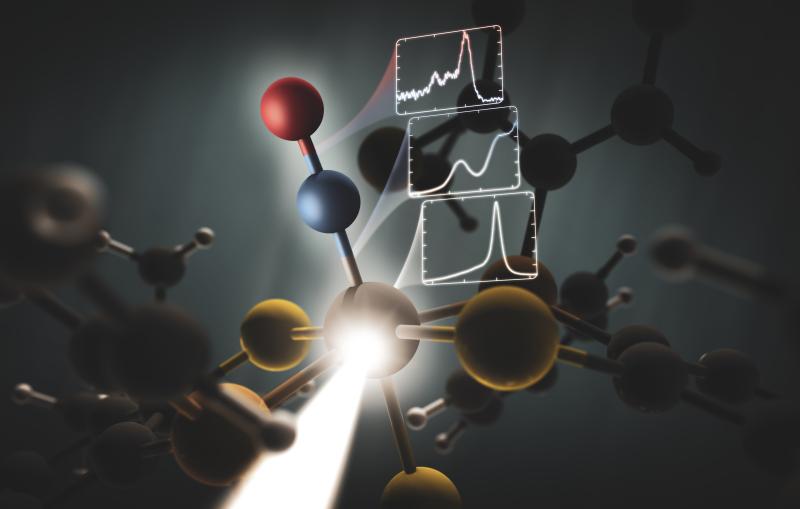

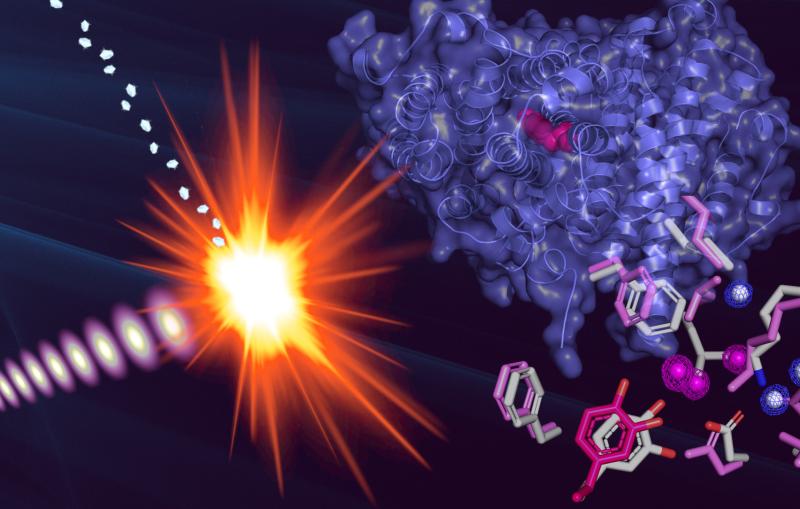

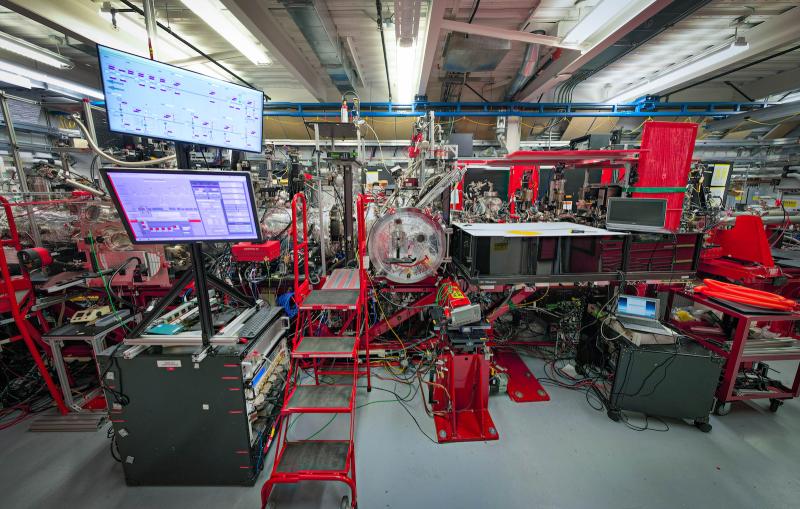

Understanding why proteins interact with certain specific molecules and not with the myriad others in their environment is a major goal of molecular biology. Now, in a series of recent papers, researchers describe how they designed proteins from scratch to have a high affinity and high specificity for targets on flu viruses, and then validated the two best designs using X-ray diffraction data collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL).

The validated proteins are now being developed as potential therapeutics against a wide range of health-threatening flu viruses. If successful, this would mark the first example of proteins with therapeutic applications being designed using a computational model, rather than starting from observations of their natural activity in the laboratory – a processed termed de novo in biology and chemistry.

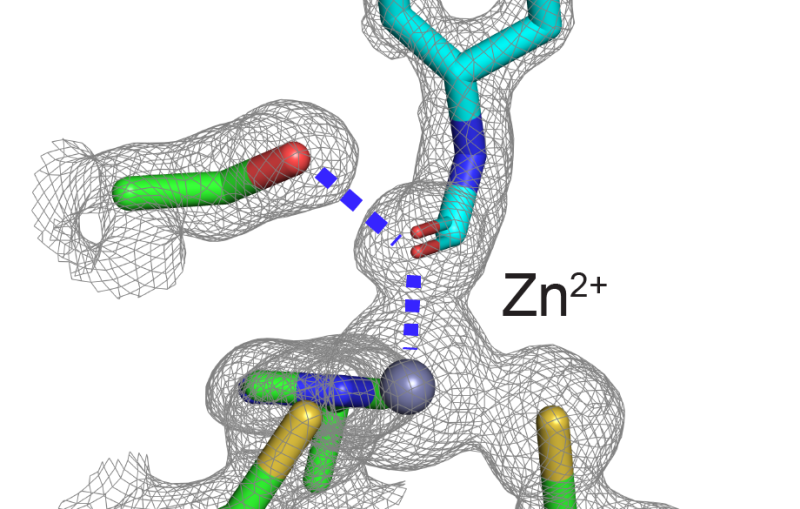

Nobel Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling had suggested in the 1940s that a combination of many weak and nonspecific interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, underlies the highly specific affinities between some molecules.

Following on that insight, a team led by David Baker of the University of Washington used massively parallel computing to virtually sift through numerous configurations of more than 800 natural proteins in search of a few configurations predicted to interact weakly with the target, a protein that enables flu viruses to attach to and invade cells lining the human respiratory tract.

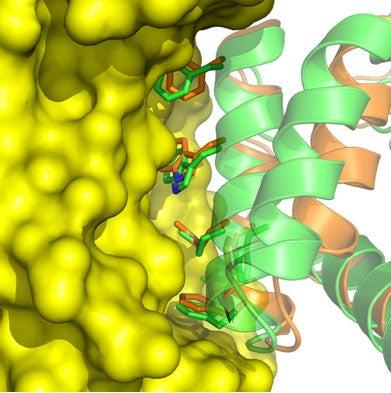

A total of 88 of the computer-designed proteins were produced in the lab, and further experiments isolated two of them that bound specifically to the target site. After additional optimization, the two proteins were shown to bind to the Spanish and avian flu versions of the flu target protein with very high affinity. They also blocked the replication of H1N1 flu viruses in human cell cultures. What’s more, studies at the SSRL showed that the structural details of the binding between these two designed proteins and Spanish flu protein were virtually indistinguishable from those designed in the computer, providing crucial atomic-level validation for the computational methods.

The team also made significant breakthroughs in understanding the design principles of natural functional sites while developing the computational methods they used to design their interactions.

The Structural Molecular Biology program at SSRL is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the National Center for Research Resources.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.