Team Uses SSRL to Decipher Structural Details of Deadly Enzyme

A small team of researchers has used the brilliant X-rays of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory to pin down the crystalline structure of an enzyme complex that scientists had spent nearly a decade trying to resolve.

By Lori Ann White

A small team of researchers has used the brilliant X-rays of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory to pin down the crystalline structure of an enzyme complex that scientists had spent nearly a decade trying to resolve. Their discovery could lead to anti-microbial agents for a host of deadly bacteria, including anthrax, tuberculosis, leprosy and diphtheria.

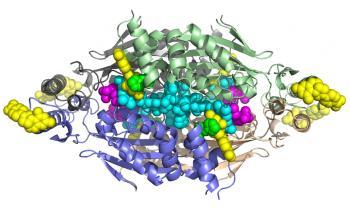

These bacteria use the enzyme, called flavin-dependent thymidylate synthase (FDTS), to synthesize a nucleotide they need to produce DNA. Other organisms, including humans, rely on a different version of the enzyme to accomplish this vital process; and the two versions of the enzyme differ significantly enough that targeting the bacterial form via drug therapies should not interfere with the human enzyme’s work.

In other words, there’s a low probability that drugs targeting the bacterial version of the enzyme will cause side effects in people.

According to SSRL Staff Scientist Irimpan Mathews, a corresponding author of the study published online last week by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the difficulty in solving the enzyme’s structure lay in crystallizing a version of the enzyme that could show them precisely what part of it a drug would need to target.

The target researchers had been trying to isolate is the site where FDTS binds with a compound called methylenetetrahydrofolate during nucleotide synthesis. “No one could get a structure of FDTS bound with that or with similar compounds,” Mathews said. This was akin to knowing what door researchers wanted to create a key for, but not being able to find the lock.

Advances in growing crystals for analysis, coupled with X-rays from SSRL beamlines 9-2 and 12-2, have given them the lock. “Our work represents the first structures of FDTS with methylenetetrahydrofolate and its mimics,” Mathews said.

Mathews sees in the discovery a novel avenue for designing drugs that inhibit a wide variety of harmful bacteria. “Many of the microbes that use FTDS are deadly, and some of them are biological warfare agents,” he said. Many on the list also cause the opportunistic infections that often strike suffers of autoimmune diseases. “If we can make a good inhibitor for the FDTS enzyme, it could in principle kill more than 20 different microbes,” he said.

The Structural Molecular Biology program at SSRL is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the National Center for Research Resources.