X-ray Laser Probes Biomolecules to Individual Atoms

An international team led by the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has proved how the world's most powerful X-ray laser can assist in cracking the structures of biomolecules, and in the processes helped to pioneer critical new investigative avenues in biology.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

An international team led by the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has proved how the world's most powerful X-ray laser can assist in cracking the structures of biomolecules, and in the processes helped to pioneer critical new investigative avenues in biology.

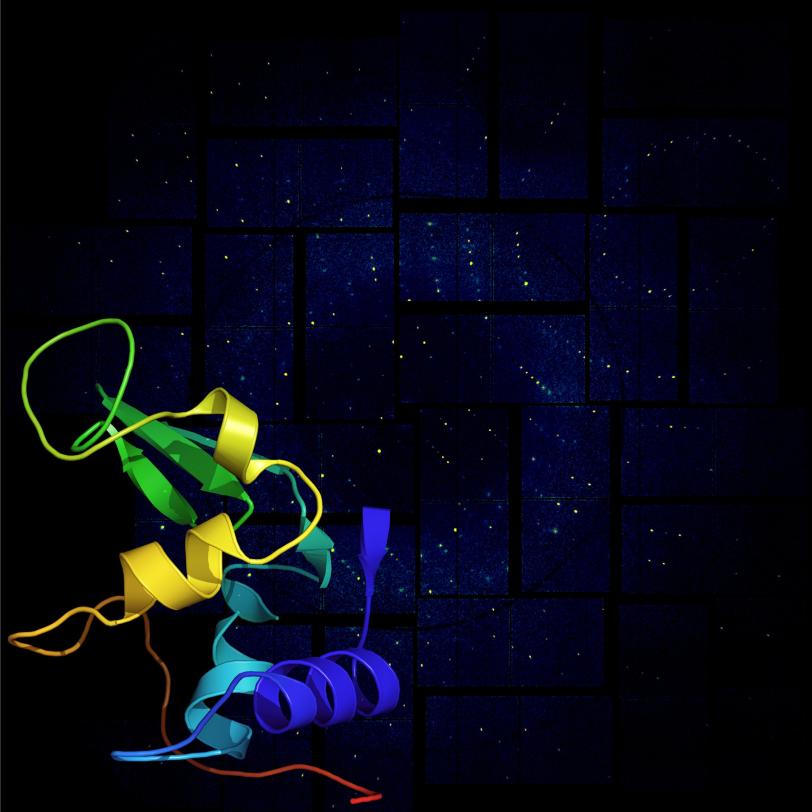

The team's experiments, reported this week in Science, used SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to obtain ultra-high-resolution views of crystallized biomolecules, including a small protein found in egg whites called lysozyme.

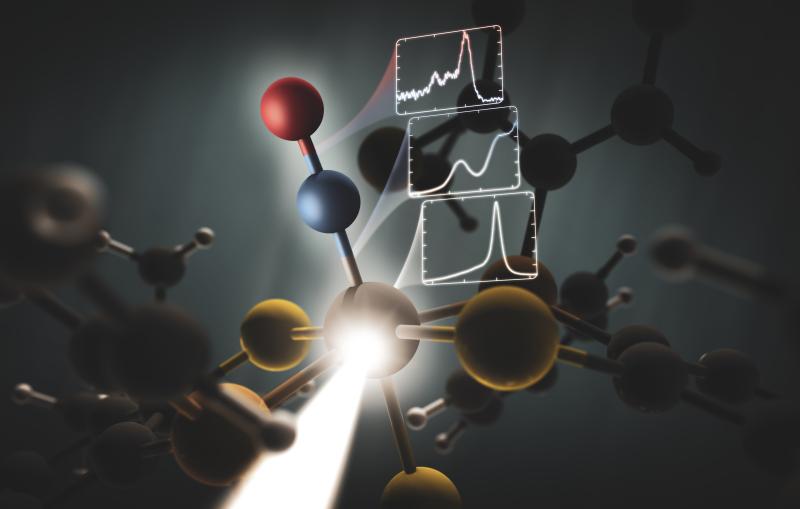

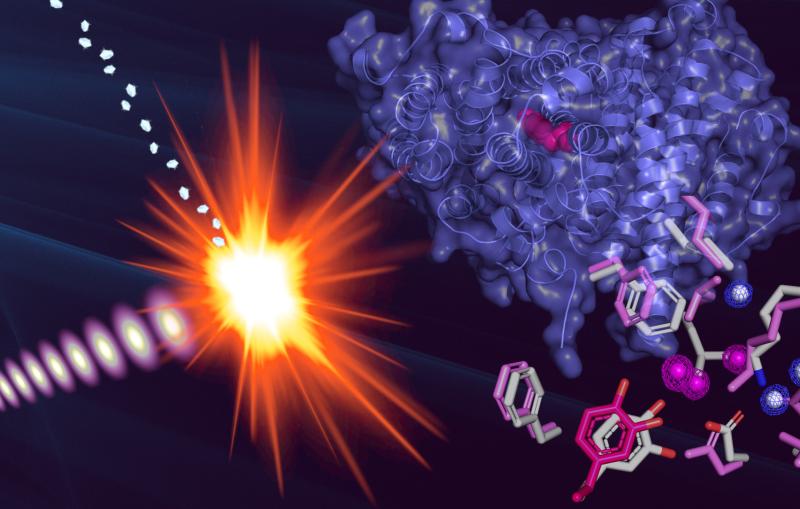

For decades, scientists have reconstructed the shape of biological molecules and proteins by illuminating crystallized samples with X-rays to study how they scatter the light. The team's work with lysozyme represents the first-ever high-resolution experiments using serial femtosecond crystallography -- the split-second imaging of tiny crystals using ultrashort, ultrabright X-ray laser pulses (a femtosecond is one quadrillionth of a second).

The technique utilized a higher resolution than previously achieved using X-ray lasers, allowing scientists to use smaller crystals than typical with other methods, and could also enable researchers to view molecular dynamics in a way never before possible.

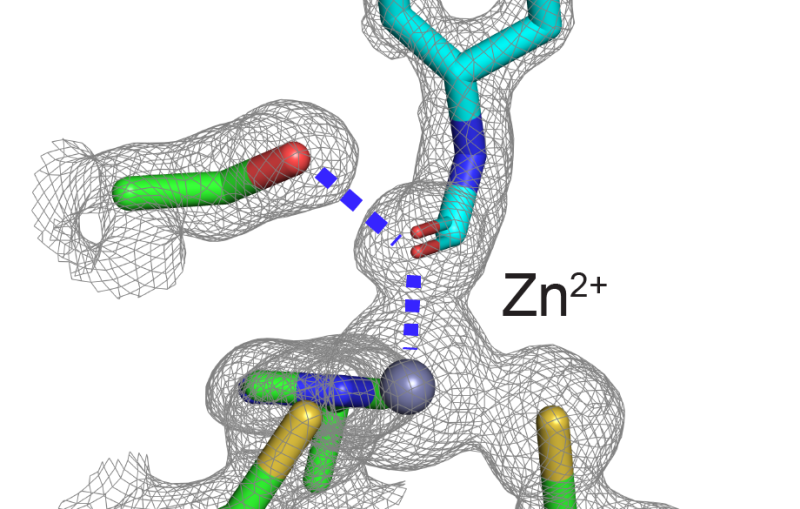

“We were able to actually visualize the structure of the molecule at a resolution so high we start to infer the position of individual atoms,” said Sébastien Boutet, a staff scientist at LCLS who led the research.

“Not only that, but the structure we observed matches the known structure of lysozyme and shows no significant sign of radiation damage, despite the fact that the pulses completely destroy the sample. This is the first high-resolution demonstration of the ‘diffraction-before-destruction’ technique on biological samples, where we’re able to measure a sample before the powerful pulses of the LCLS damage it,” he added.

The team chose lysozyme as the first sample for their research because it is easy to crystallize and has been extensively studied. Their work not only determined lysozyme’s structure at such high resolution that it showed individual amino acids, but also proved the ability to use extremely small crystals for a range of applications. Boutet says the team has also studied more complex proteins and systems that they are analyzing now.

Ultimately, scientists using LCLS are driving toward an atomic- and molecular-scale understanding of complex biological systems -- such as the membrane proteins that are critical in cell functions and the mechanisms that power photosynthesis -- which could lead to discoveries in a range of sciences, from pharmaceutical breakthroughs to new sources of alternative energy.

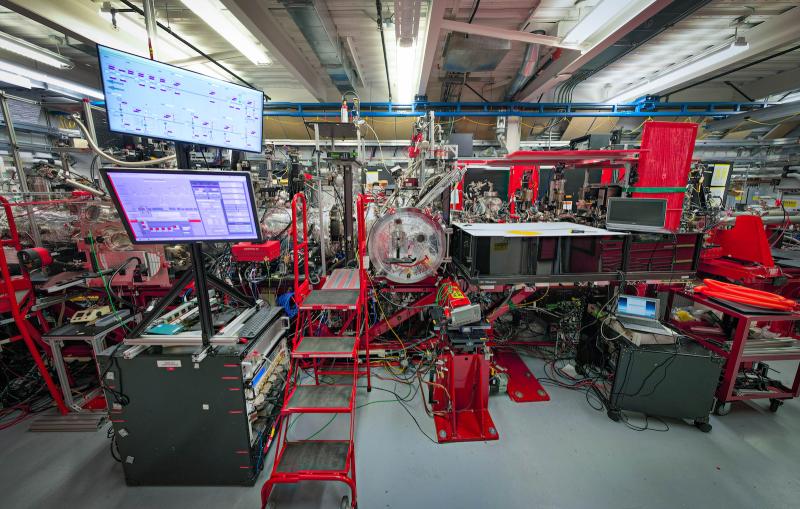

The experiment was the first study performed on the new Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) instrument, a “molecular camera” designed, built and commissioned by SLAC and now available to the scientific community. Also key to the study was a novel custom-made detector, the Cornell-SLAC Pixel Array Detector (CSPAD), developed in collaboration between Cornell University and SLAC for use at the CXI instrument.

"This important demonstration shows that the technique works, and it paves the way for a lot of exciting experiments to come," says Boutet.

Members of the international team included researchers from Max Planck Institutes, DESY, Arizona State University, Cornell University, SUNY Oswego, The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, the Nikhef National Institute for Subatomic Physics, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, the University of Gothenburg, the University of Hamburg, the University of Lübeck and Uppsala University.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.