Scientists Use LCLS to See Photovoltaic Process in Action

A surprising atomic-scale wiggle underlies the way a special class of materials reacts to light, according to research that may lead to new devices for harvesting solar energy.

By Mike Ross

A surprising atomic-scale wiggle underlies the way a special class of materials reacts to light, according to research that may lead to new devices for harvesting solar energy.

For decades, scientists have known that some ferroelectric materials – materials that possess a stable electrical polarization switchable by an external electric field – are also photovoltaic: They produce an electric voltage when exposed to light, just as solar cells do. But it was not clear how the light induced voltages in these materials.

Such insight is very useful to researchers hoping to design ferroelectrics with improved photovoltaic properties for use in solar cells and other applications, such as sensors and ultrafast optical switches for data and telecommunications networks. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed, with many open questions still remaining.

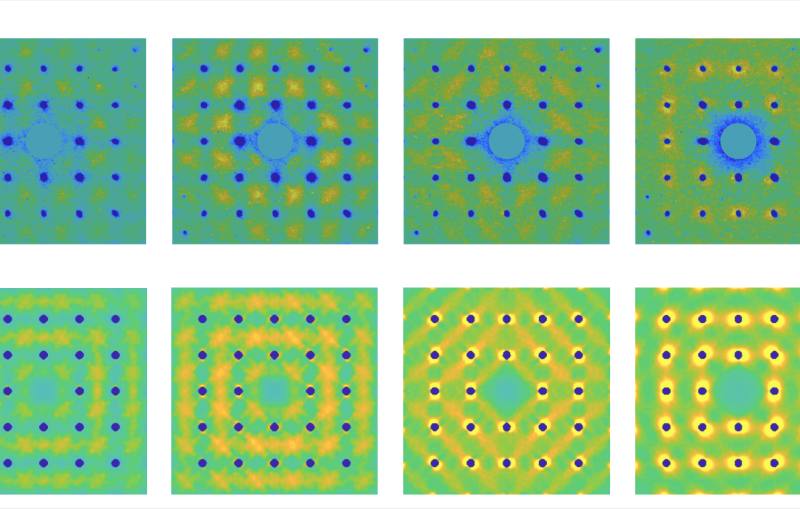

Now, in research published last week in Physical Review Letters, scientists led by Aaron Lindenberg of SLAC’s Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences and the Stanford Materials Science and Engineering Department, along with graduate student Dan Daranciang, have determined first-hand what is going on: Stop-action X-ray snapshots of a ferroelectric nanolayer showed that the height of its basic building block, called a unit cell, contracted in response to bright light and then rebounded to become even longer than it was to begin with.

The entire in-and-out atomic-scale wiggle took just 10 trillionths of a second, yet it indicated the mechanisms responsible for the materials photovoltaic effect. “What we saw was unanticipated,” Lindenberg said. “It was amazing to see such dramatic structural changes, which we showed were caused by light-induced electrical currents in the ferroelectric material.”

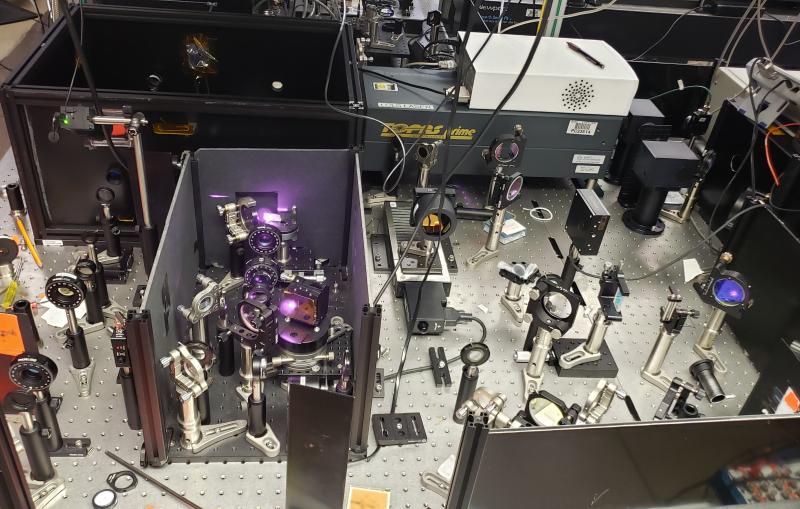

The telling X-ray images were taken at the X-ray Pump Probe instrument of SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), which hit the ferroelectric samples with a stunningly rapid one-two punch of violet laser light (40 quadrillionths of a second long) and X-rays (60 quadrillionths of a second long). The researchers analyzed information from thousands of images to determine the photovoltaic mechanism.

The fact that ferroelectric materials produce much higher voltages than conventional silicon-based materials makes them an attractive option for making solar cells, Lindenberg said. But their very low light-conversion efficiency has precluded commercial applications. Now that researchers understand the underlying mechanism, he said, they can more effectively create ferroelectric materials that are more suitable for photovoltaic applications.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

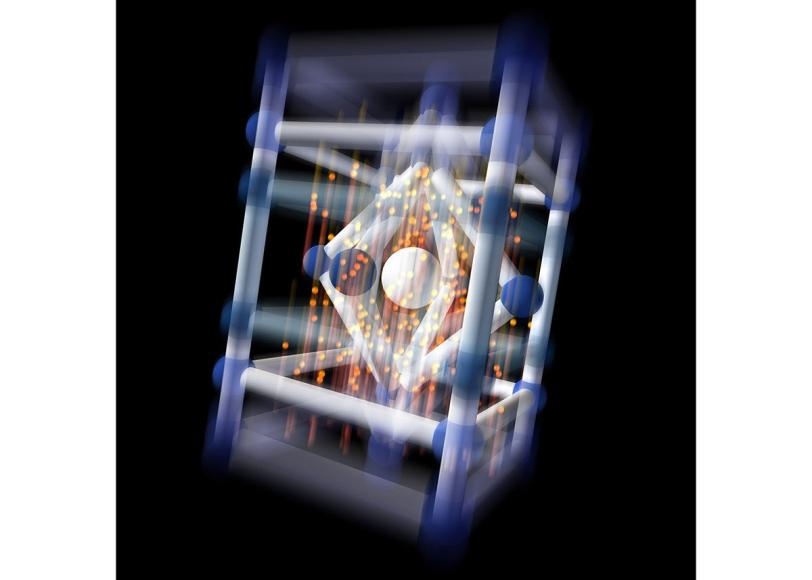

(Illustration by Gregory M. Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)