Sorting Millions of Snapshots from the LCLS

The great thing about SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source is that it churns out incredible volumes of data about things no one has ever seen before, such as snapshots of individual viruses.

By Glennda Chui

The great thing about SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source is that it churns out incredible volumes of data about things no one has ever seen before, such as snapshots of individual viruses.

The hard thing is: What to do with all that data? Of the several million snapshots scientists might get in a single, 10-hour shift of zapping samples with a powerful X-ray laser beam, fewer than 1 in 100 will contain the information they’re looking for.

This is the problem that Abbas Ourmazd and colleagues Peter Schwander and Chun Hong Yoon of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee are working on. They’re members of an 80-plus person collaboration, including SLAC scientists from the LCLS and the PULSE Institute for Ultrafast Energy Science, who performed groundbreaking experiments on large viruses and tiny protein nanocrystals with the world’s most powerful X-ray laser in December 2009.

In an Aug. 12 report in Optics Express, the team outlines a method for automatically sorting those millions of snapshots so most of the good shots end up in just one bin. Further analysis of the data in that bin should yield a 3-D image of the original object, Ourmazd said, whether it’s a virus or a tiny grain of “nanorice” that’s used as a test subject in these studies.

“Computer analysis – making sense of all this beautiful data coming out of the LCLS – has turned out to be as difficult and as important as the data acquisition,” Ourmazd said in an interview.

He describes the problem this way:

“Say, for example, you make a solution full of virus and you spit little droplets of the solution into the X-ray laser beam” with an injector that sprays them in a fine mist. ”Each droplet can be empty, or it can have one virus particle in it, or it can have multiple particles in it,” Ourmazd said. “Also, the solution is not necessarily pure, so you can have different kinds of particles being spat out individually or in combination.

“In addition, the X-ray intensity varies from shot to shot. Even when it’s the same, the laser beam may miss the particle, hit it square on, or just hit some of it and not the rest. What you would like to do is take these snapshots and from them extract the droplets that contain a single copy of a single virus which has been nicely hit.”

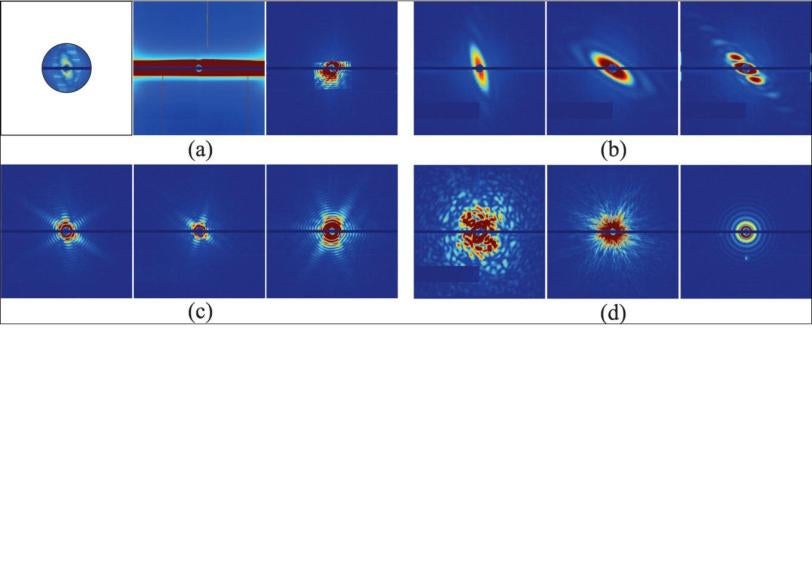

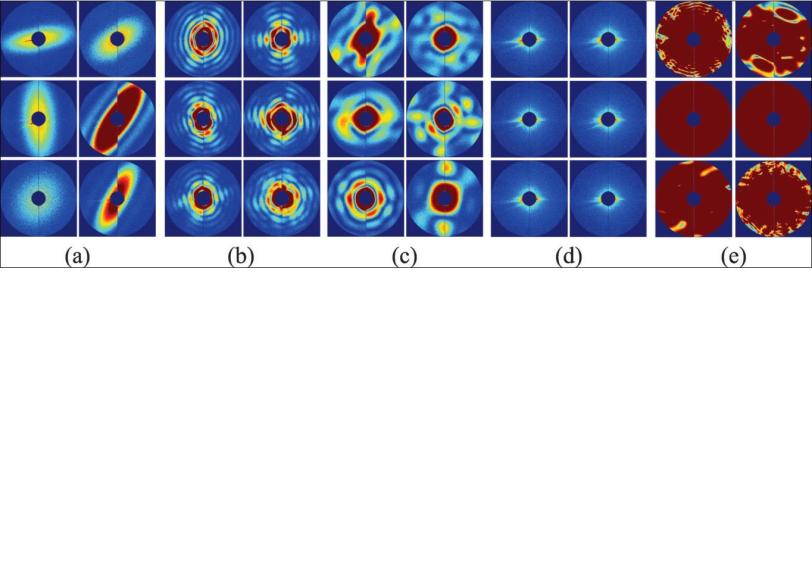

When the X-ray pulse hits the virus, it forms a diffraction pattern in a detector, and thousands of those patterns can be combined to get the structure of the virus. The challenge is to do this automatically, without direct human supervision; without bias; with high precision; and really fast.

Ourmazd, Schwander and Yoon are part of a theory group that is developing algorithms for analyzing the terabytes of data coming out of the LCLS. Their approach combines mathematics, scattering physics and information theory. Ourmazd is a distinguished professor of physics; Schwander, a senior scientist specializing in physics and informatics; and Yoon, a postdoctoral researcher and electrical engineer.

The simplest way to think about their method, Ourmazd said, is to start with the idea that experimental data is correlated – it hangs together, somehow – while background noise is random. You can think of the correlated data for each snapshot of an object, whether it’s a full-on hit or a glancing blow, as lying on a surface. “The interesting information content is in the shape and in the wrinkles of the surface,” he said. The question is, what is the characteristic wrinkle pattern and shape that distinguish one type of object from another, and good shots from mediocre ones?

The algorithm found these patterns of correlation and used them to sort 7,214 snapshots of nanorice and viruses. The results showed 90 percent agreement with sorting done manually by a human expert. The researchers estimate that a million snapshots can be sorted in less than 10 hours with this technique.

“You go to the data with no preconceived notions. All the information is in the wrinkles and the shape of the data set,” Ourmazd said. “It’s a wonderful combination of mathematics and information theory.”

Once you’ve done that, he said, you should be able to open the bin that contains full-on images of nanorice grains or viruses, taken from all possible angles as the tiny particles tumbled through the X-ray beam, and reconstruct their structure in 3-D.

Ourmazd said the team is already applying this approach to data from LCLS experiments, images taken with cryo-electron microscopy and free-electron laser studies of changes in individual molecules.

“We feel like kids in a toy store,” he said, “totally confused by the choices and overwhelmed with pleasure.”

Related Links

- “Unsupervised classification of single-particle X-ray diffraction snapshots by spectral clustering,” Optics Express, Aug. 12, 2011

- “Giant Virus, Tiny Protein Crystals Show X-Ray Laser’s Power and Potential," SLAC News Center, Feb. 3, 2011