michael peskin: greetings and welcome to the latest installment of the SLAC public lectures of this year we're celebrating the 60th anniversary of SLAC.

michael peskin: And many of the themes of this anniversary, have to do with new scientific activities in which SLAC is pioneering and so many of the public lectures this year will deal with those themes, and this is certainly one of them.

michael peskin: We have this amazing new facility called Cryo-EM which will be explained in this lecture which produces amazing images of biological structure.

michael peskin: And we're going to hear today a lecture that takes advantage of that facility to tell some amazing things about the biology of viruses.

michael peskin: The speaker is Rachel Kretsch she's a graduate student in biophysics here at Stanford a student of Professor Rhiju Das and one of those people exploring now new details of viral RNA structure that only become apparent with this technique.

michael peskin: She has an interesting history. michael peskin: She comes originally from the Netherlands, she studied at Harvey Mudd on she's wandered around the world, a little before landing at Stanford and now she's engaged in this very interesting activity which she's about to tell you that.

michael peskin: um, let me just say one more thing, before we begin, we will have a question and answer session at the end of this lecture you'll see at the bottom of your zoom screen a Q&A box.

michael peskin: And so, please open that up if you have a question type in your question and we'll ask all those questions of Rachel and her colleagues who are here as panelists after the end of the lecture.

michael peskin: So, with no further ado I introduce Rachel Kretsch and she's going to tell you about revolutionary 3D views of viral RNA, so please okay.

Rachael Kretsch: Thank you, Michael yeah so as Michael said i'm Rachel and I want me to tell you guys.

Rachael Kretsch: Today, about rnas. Rachael Kretsch: Their structure and how we study it with cryogenic electron microscopy or as how we call it Cryo-EM.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's begin with just a brief introduction of who I am, some of which Michael has already gone over.

Rachael Kretsch: So I grew up in the Netherlands and a beautiful city, called the Hague and then some of my exposure to science was really with this organization called OPCW.

Rachael Kretsch: which works on chemical weapon issues so from an early age, I was really engaged, not only in science, but also how it can impact society.

Rachael Kretsch: And then I had it to Harvey Mudd, which is a great little school in Southern California there I studied the 3D structure of molecule so there's just an example at the bottom of this slide.

Rachael Kretsch: And I also fell in love with the mountains around here and hiking and one of the reasons i'm back in California Now for my PhD.

Rachael Kretsch: I took a year to then dive into my interest in science and society and, specifically, science and security in London, you can see the beautiful Christmas decorations around where I lived.

Rachael Kretsch: And also got the opportunity to work with wonderful researchers at two centers one in Monterey and one in Los Alamos and that's how I ended up here.

Rachael Kretsch: So now i'm at Stanford and I'm part of the biophysics program and also a fellow at Bio-X, so what I do is truly interdisciplinary so I studied biological questions.

Rachael Kretsch: But I do so using knowledge from chemistry physics and computer computation.

Rachael Kretsch: And I do this in two labs and so first Rhiju Das lab so the DAS lab which are experts on this molecule called RNA and what its shape or structure is, and then the Chiu lab which are experts on the electron microscope that allow us to see RNA.

Rachael Kretsch: And because we need these very powerful microscopes to see RNA I do all my imaging here at SLAC so at the Center called S2C2 to that has a few of these microscopes and i'm lucky enough to get time on them to see my RNA.

Rachael Kretsch: And I also just want to highlight that no scientists can do their work alone we're all surrounded by a massive community of other scientists.

Rachael Kretsch: here's just a small selection of some people in my community, and I want to highlight the following people that contributed or lead the work that i'll be talking about today.

Rachael Kretsch: So in blue we have timings how many and cali and they were the three that lead their original effort to show that Cryo-EM, this technique i'm going to be talking about can be used to solve the shape of a variety of different RNA.

Rachael Kretsch: And then in pink we have Vonia, KaiMing and Rachel who led the effort to study the RNA and i'm going to be talking about as an example, today, that is from the SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so I like to start my lectures with the takeaways and hopefully by the end i'll convince you of some of these takeaways.

Rachael Kretsch: So the first is that RNA viruses are a large challenge to human health, but structural biology offers us clues on how they work and that's how we may think about stopping them.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we have decades of technological development and basic science that enable our current response to these viruses.

Rachael Kretsch: RNA is a key component of these RNA viruses, but its structure has remained a mystery for much of history.

Rachael Kretsch: And then Cryo-EM is, finally, enabling us to actually look at these RNA.

Rachael Kretsch: So we're going to split this into five parts, the first, is what is structural biology then we're going to learn about what RNA viruses are we're going to learn that there's four levels of RNA structure and we're going to go through the example.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we're going to show how we study RNA 3D structure, using the Cryo-EM.

Rachael Kretsch: And then finally we're going to ask what the structures can actually tell us about the virus.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's start with what structural biology yes. Rachael Kretsch: So if you Google structural biology you're going to end up with a bunch of images I look something like that.

Rachael Kretsch: And quite frankly I wouldn't know how to interpret or what a lot of these images are, but the basic to structural biology is we care about the shape.

Rachael Kretsch: Of these molecules, for example, we have three rings and the ring is probably important for what these molecules to do, and we have other shapes like spheres or diamonds.

Rachael Kretsch: So, to simplify it let's look at at analogy, and in this analogy we're going to have a character that's going to start at the starting line here, and the question we're asking is whether this character can make it through this tube to reach the other side in our 3D scene.

Rachael Kretsch: So if I give you the first level of structure it's just the list of building blocks, so we know the character, has a red hat brown shoes of black mustache but that's all we know and that's insufficient to tell us whether it can fit in the tube.

Rachael Kretsch: Then we go to the second level structure which is how the parts are connected, so we know the shoes, are at the bottom are connected to the overalls and then the hats on top.

Rachael Kretsch: But we still don't know the exact dimension to shape that would allow us to ask whether it can fit through the tube we need the 3D structure for that, and once we have the 3D structure we can fit them in the scene and we see he's slightly too tall to fit into that too.

Rachael Kretsch: But this is because we've missed the fourth level of structure and that's the fact that these shapes can change and move, so in this case, our character is able to lower his hands and then lay down in order to get through the two.

Rachael Kretsch: Right. Rachael Kretsch: Now if that's what he wants to do so, he wants to make it to the other side is there, something we can do to stop him from being able to get through the tube.

Rachael Kretsch: And the answer is yes, we can give him a bunch of coins now he's busy holding his coins and can no longer lay down and make it through the tube.

Rachael Kretsch: So we're also interested in how our character interacts with other things like the coins, so how does this relate to biology well in biology, the scene is the cell.

Rachael Kretsch: And the characters in the scene, or what we call macro molecules which just means big molecules now remember it's in 3D So you can see down here we have a 3D shape it's kind of like a mouth.

Rachael Kretsch: And this is actually the ribozome that will be talking about a little bit today so biology happens when macro molecules interact in itself.

Rachael Kretsch: And we have two questions, we want to ask about them, how do they work, so in the case of Mario he put his hands down and laid down to make it through the tube.

Rachael Kretsch: And then, how can we stop it working so in the case of Mario we gave it a bunch of coins, but in case of our biology it's often through drugs.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so what micromolecules are you talking about well today we're really focusing on RNA which I pictured here.

Rachael Kretsch: And RNA is a close cousin of DNA that you may have heard of DNA is what humans store their genetic information and RNA and humans is just a direct copy of the DNA, so you can see, we just directly copy over the colors from DNA RNA.

Rachael Kretsch: RNA is a sequence of four bases, so we have A C U and G.

Rachael Kretsch: And the full name is ribonucleic acid so i'll probably will never say that again in this lecture we tend to call it RNA.

Rachael Kretsch: And one of the main functions of RNA is to make proteins so RNA gets what we call translated to protein, now we see a problem here.

Rachael Kretsch: RNA is made off for basis right A C U G, but proteins have 20 building blocks, or what we call amino acids So how do we do this well every three at a time.

Rachael Kretsch: So we have three bases of RNA that make up one amino acid, and then the next three makeup but different amino acid, and then we continue on reading the RNA three at a time and translating it to one amino acid, and we continue onwards.

Rachael Kretsch: Now, in reality, or proteins are larger than small protein I picture previously so, for example, the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 that you may have heard about is 1000 amino acids, so that means 3000 basis of RNA go into translating into that protein.

Rachael Kretsch: And this simple model of how DNA and RNA and protein are related is just that simple so RNA is not just a messenger and hopefully today you'll see one or more examples of that.

Rachael Kretsch: And RNA has shaped too so i've kind of just drawn it as a string but there's plenty of different RNAs that have a 3D shape, just like that protein does.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's watch translation happen because that's what we're going to be focusing on today.

Rachael Kretsch: So this is a 3D video it's not real life it's just a simulation we have the RNA and yellow here looking like a string we have a protein and red up top.

Rachael Kretsch: And then, this blue is the ribosome that's the machine that's doing the translating so we can watch the ribosome pool the RNA through it, making the protein up top.

Rachael Kretsch: And what it's doing is reading three bases and putting one amino acid on top can notice all these 3D structures moving around and fitting in nicely together.

Rachael Kretsch: And the protein comes out the other end and folds up now, it would be great if we could actually see this in real life.

Rachael Kretsch: But unfortunately, all of this is much too small for us just to see so we're going to zoom in and to the size of RNA starting at size 12 font and a grain of rice, we are going to be zooming in past a grain of salt past the skin cell that's your human skin cells.

Rachael Kretsch: We now are going to start seeing viruses like HIV there's the ribosome, I was a big machine.

Rachael Kretsch: And then, here we have RNA and if we zoom back out, we can see we're getting bigger and bigger the RNA, we can no longer see at this point we have yeast which makes your bread.

Rachael Kretsch: And we zoom all the way out back to a grain of salt and coffee bean. Rachael Kretsch: So biology is very, very small we can't simply see it you can't even use one of these microscopes so we use an electron microscope.

Rachael Kretsch: And what that means is it magnifies it 100,000 times to put that into perspective, a human would not be 18,000 football pitches long.

Rachael Kretsch: But our RNA started so small at this type of magnification, it is now around one millimeter or the size of a grain of rice so it's now visible, but still pretty small.

Rachael Kretsch: Now there's a second problem to look at structural biology and it's the fact that this cell is incredibly crowded.

Rachael Kretsch: So here's an artist's rendition of what a cell may look like, and you can see i've labeled here that ribozome that was that big machine in the video and the RNA that's getting translated and pink.

Rachael Kretsch: And you can see lots of ribosomes translating different RNA but there's also a lot of other stuff in the south right it's a very crowded environment.

Rachael Kretsch: And you can imagine if I was to take a picture of this, it would be very hard to point out what, which was the RNA and what was other things right.

Rachael Kretsch: So we don't actually image, the cell we just image RNA alone in salty water, so we don't have to deal with picking it out and differentiating it from everything else in the cell.

Rachael Kretsch: So i'm gonna release a secret that structural biology is not going to solve the world's problems, and it is more of a tool to give us insights into solving the problems, so I liken it to a textbook.

Rachael Kretsch: So a textbook does not solve your problems, but you still consult the textbook when you want to solve a problem because it gives the necessary background about how to solve the problem.

Rachael Kretsch: structures are very similar to biology, they will not tell you how the macro molecule works or what drug will stop it working.

Rachael Kretsch: But you still solve a structure, when you want to understand the biology, because it forms your hypotheses on how it may function and what drug may affect it.

Rachael Kretsch: So they inform how micro molecules may work and how we may stop them working but it's not the end of our work, we still have work afterwards.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so let's learn what RNA virus are Rachael Kretsch: and the first thing to realize is how important they are so here's a list from the World Health Organization of what they deem the diseases of most pandemic and epidemic concern and i'm just going to highlight which of these are RNA viruses.

Rachael Kretsch: it's the vast majority of them, so you can see some viruses like influenza that causes flu, or even the coronavirus that we are currently battling.

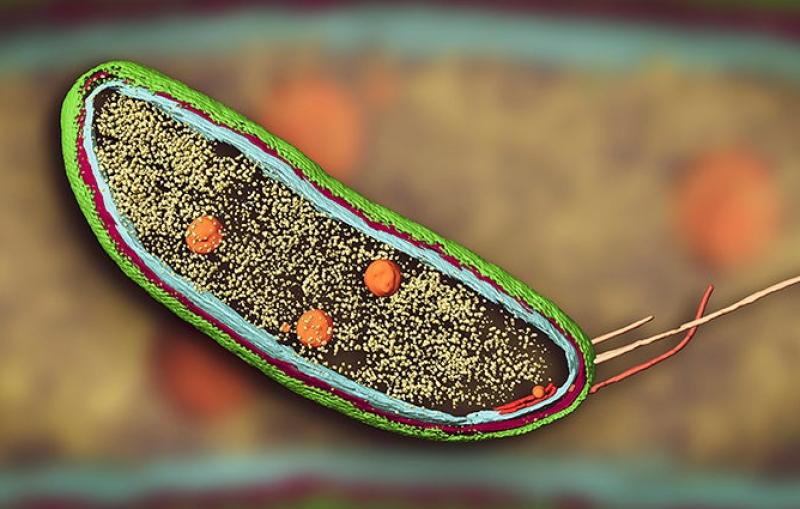

Rachael Kretsch: So what are these viruses well here's a picture on artistic picture of the coronavirus and in yellow and green we have mucus of our lungs that's, the environment, the coronavirus is floating around in.

Rachael Kretsch: In pink in the sphere, we have the coronavirus spike protein that you may have heard of and then packaged away in the middle, is the coronavirus RNA and that's what we're really interested in studying and here's one reason why.

Rachael Kretsch: When the coronavirus and paints here infects the human cells, so you have the human cell in blue, what does it actually inject well.

Rachael Kretsch: it's the RNA so the RNA of the coronavirus has what enters ourselves it starts to get translated to make viral proteins and also gets copied to make more and more copies of the virus.

Rachael Kretsch: So we're going to refine our DNA RNA protein for RNA virus is it really truly is just RNA protein right so we're getting viral RNA and then we're translating that to make viral proteins.

Rachael Kretsch: Okay, how do we study. Rachael Kretsch: The RNA so we have four levels of structure.

Rachael Kretsch: And I already went through with the analogy of our character here the four levels of structure, so we have the list of building blocks, then we have how these building blocks are connected, then we have the actual 3D shape and finally we have how it moves or interacts with other things.

Rachael Kretsch: And then, all RNA we have very similar four levels of structure, and we have different types of experiments that can give us information at the first level or the second or the third or the fourth level.

Rachael Kretsch: And as we go up in levels of structure we learn more and more about our RNA and how it works and how we can stop it working.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's start at the first level which is simply the sequence, so you already know there's four building blocks G you A and C and the sequence is simply the order that these building blocks are in.

Rachael Kretsch: So we want to determine the primary structure for the sequence of the RNA of coronavirus.

Rachael Kretsch: And this was done incredibly quickly probably before many of you had known, the existence of COVID-19.

Rachael Kretsch: So, in January 10 2020 the first full sequence of the coronavirus RNA was published and how was it that we could get this so quickly, well, it really was technological advancements that allowed us to do this, so this is a graph we started in 2001 down here and we go to present day.

Rachael Kretsch: And here we have the cost of sequencing so the white line is having the cost, every year, so that's already a great trend.

Rachael Kretsch: But you can see, we did much better than that, and that was because new technology came out called next generation sequencing.

Rachael Kretsch: And what that allowed is now the cost of sequencing one SARS-cov-2 genome is only about $34 by some estimates, so now we can sequence, you know genomes from around the world and from different patients.

Rachael Kretsch: And I just want to point out on this timeline that we had an outbreak of a cousin of SARS-cov-2 to SARS-cov-1 one back here, it was only roughly 15 years ago, but the cost to just sequences of virus would have been much more expensive and it would have been much slower.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so here's the primary sequence it's simply a list of A C G and Us, and there's 30,000 of them roughly.

Rachael Kretsch: Now just reading a bunch of ACG and Us are not going to tell us much information, but we can compare it to other viruses to identify closest relatives so that's how we know, it was a coronavirus, for example.

Rachael Kretsch: We can also track changes in this sequence, which tells us new variants that you may have heard of.

Rachael Kretsch: And what's of interest to days we can actually identify what proteins are being made because we know through translation there's a direct.

Rachael Kretsch: mapping from the RNA sequence to the protein sequence, and that was an interest for the spike protein so for this fight protein the ribosome will bind here and the RNA sequence, and it will translate this part of the RNA to make the spike protein here's the spike protein over there.

Rachael Kretsch: it's what our cells see and that's why it's so important because it's what our human Defense or the immune system sees and tells us that were being infected by the virus.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so we wanted to know the shape of the spike protein and due to the advances in Cryo-EM, this was solved in little over a month that is incredibly fast and we were very impressed.

Rachael Kretsch: Now one thing to note right is, this is a protein the the field is much more advanced proteins I work on RNA we're not quite able to sell these structures within a month, yet.

Rachael Kretsch: But the fact that we're able to do this for protein gives us hope that maybe years down the line, will be able to do this RNA as well, so I said, you know Cryo-EM was an important factor here let's go through what Cryo-EM is.

Rachael Kretsch: So here we have a schematic of chromium we start in the middle here where our protein or RNA is frozen and ice.

Rachael Kretsch: Okay, and you notice, some of them are up some of them sideways someone them downwards, so we have multiple copies of our protein RNA and they're all in different orientations.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we have an electron beam that comes through and hits the protein or RNA and makes an image, on the other side.

Rachael Kretsch: And these images, some of them are upward facing sideways facing bottom facing right.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we take thousands or millions of these images we organize them by their orientation, so we have sideways facing upward facing etc, and we use a computer algorithm to reconstruct the 3D shape from these images.

Rachael Kretsch: So i'm going to focus on how we actually get the sample so in my case, I just have RNA and salty water and I apply it to this grid here.

Rachael Kretsch: And I tried to get the thinnest layer possible. Rachael Kretsch: And then I dip it into liquid ethane, which is extremely cold negative 196 degrees to freeze it very quickly, so now, I have a very thin layer of ice and all my RNAs are frozen in time and I keep it at this temperature so that's why it's called cryo which means cold.

Rachael Kretsch: As I images and you can see here, I have now a nice thin layer that my electrons are going to pass through.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's look at that, in a little more detail in this video, so we have a grid it's made out of copper.

Rachael Kretsch: And it's only roughly a 10th of an inch in diameter, so you can imagine it's very, very small and we handle it very, very carefully we're going to zoom in into one of these squares and these squares here are covered in the layer of carbon.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we have these holes, which is where we're going to do our imaging so in these holes it's simply a layer a thin layer of ice with my RNA or protein in it, and we can zoom in and look at this view.

Rachael Kretsch: See here, in this case it's ribosomes actually so that machine you're talking about earlier and they're all in different orientations right some upwards and downwards, but they're frozen in time.

Rachael Kretsch: All right, let's look what it looks like to image so we're looking from the top now at our whole and then we take an image, the electrons go through and make an image, on the other side in reality it's much noisier than this, this would be a perfect scenario, and then we extract the images.

Rachael Kretsch: And we sort them by the orientation, so we have a group that side, looking at group that's from the top and a group that we're looking from the bottom.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we use a computer algorithm with all of these images to reconstruct the 3D volume here, and you notice, as we put more and more images in were able to get more and more detailed view of what the shape is so you can start to see much more details.

Rachael Kretsch: So that's the basis for Cryo-EM and just by knowing the RNA sequence, they were able to put a bunch of RNA proteins on these tiny little grids.

Rachael Kretsch: And image them with Cryo-EM and these are just some of the shapes they were able to solve when I say they I mean the scientific community lots of labs lots of collaboration.

Rachael Kretsch: Right and this you know structure is not the end, so you would then use this shape to identify how these viral proteins work and how we can actually stopped them working.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so I want to focus in on this translation.

Rachael Kretsch: So we have a group of Orange proteins here, where the ribosomes binds at the beginning of the virus and starts translating to make these 11 orange proteins.

Rachael Kretsch: And then it hits a stop saying all and it stops translating. Rachael Kretsch: We also have a group of blue proteins here.

Rachael Kretsch: More in the middle of the virus and I want you to notice something very interesting there's an overlap between the orange and the blue proteins.

Rachael Kretsch: So what that means is that the same RNA sequence is being translated into an orange protein but also part of a blue protein.

Rachael Kretsch: So, how does that work, how does the same RNA sequence give us two different proteins well let's look at the blue mechanism.

Rachael Kretsch: So the ribosome starts binding here still and it translates a bunch of Orange proteins, just like the orange.

Rachael Kretsch: But when it reaches this pink box it slips and this slip causes it no longer to make orange proteins, but instead start making blue proteins.

Rachael Kretsch: Okay that's great, but why does any of this matter so let's zoom in on this region, right here, where this slip is happening.

Rachael Kretsch: Now the slip and coronavirus happens around a corner of the time so according to the time it just reads like normal no slip three quarters is.

Rachael Kretsch: Now, what will happen if I add a drug that stops the slipping so now i'm going to get less of the blue.

Rachael Kretsch: What we like to measure is viral replication right, because every virus their goal is to copy itself and make more virus so we're going to measure how well it can copy itself.

Rachael Kretsch: So when we have no drug it copies itself pretty well but as we add this drug that stops this slipping.

Rachael Kretsch: The virus also fails to replicate right so we're actually harming the virus by stopping this slipping mechanism so it's important we want to study how it's slipping so we can try to prevent it from slipping.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's zoom in again on this region right where the slipping is happening and we're actually going to look at the RNA sequence.

Rachael Kretsch: So here's the RNA sequence again this RNA is getting translated by the ribosome right so let's just remind ourselves what translation is, we have the ribosome, big machine in blue.

Rachael Kretsch: The RNA is being pulled through the ribosome and it's reading three new three bases, at a time to add one amino acid to our protein that's getting formed up top here.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so let's do that let's translate this part of the RNA sequence.

Rachael Kretsch: So UUU gets translated into the amino acid F UUA toL the next three to an N, G, and F so that's how we ribosome reads normally three at a time.

Rachael Kretsch: What happens when we have slipping so it's it starts normally we have FLN

Rachael Kretsch: But this is when the slip happens and what this means is instead of reading GGG it slips back one and read CGG

Rachael Kretsch: which makes our instead of G, so we start making different proteins and then it continues reading G you you, which is V, so now we're making completely different proteins just by slipping back one base.

Rachael Kretsch: As an analogy let's look at some English words, so we have a list of letters here and I read out the words comic Roman goose.

Rachael Kretsch: All right, what happens if I put a slip in there, so i'm starting to read normally comic, then I put a slip so I moved back and I read micro manga comic micro mango right very different meanings very different words from the same list of letters, because I slipped.

Rachael Kretsch: And we call this a frame shift because we're shifting the frame that we're reading or translating it.

Rachael Kretsch: And the RNA here and further on, is what we're interested in studying because we think it's shape is causing this slip to happen.

Rachael Kretsch: So this is what we call the frame shift stimulation element, or, as you probably noticed, by now, you like using acronyms so we're just going to call it FSC for short and the FSC is this region of the RNA region where the slip is happening.

Rachael Kretsch: So what are we curious about well, we want to know the shape of the FSC and why we want to know, it is because we want to know.

Rachael Kretsch: Why sometimes the ribosome slips normally and why, sometimes it slips with the overall goal of informing us how it inhibits how it frame shifts and then how we could potentially inhibit the frame shifting and thus inhibit the virus.

Rachael Kretsch: So what's the primary structure well that we had back in January 2020 luckily enough um but frankly we don't really know much just based on the primary structure right it's just the list of UACGs.

Rachael Kretsch: i'm actually going to give you a sneak preview and color it by what's near each other in 3D space So you see, for example, the blue we have these regions are quite different in sequence, but far from each other in 3D space.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's learn more let's go to the second level structure, how all these things are connected.

Rachael Kretsch: So for RNA, it's quite basic, so we have ACUGs, and they just pair up so Us and As like pairing together and Cs and Gs like pairing together.

Rachael Kretsch: So, if we take this sequence, we can pair up this G, and this C

Rachael Kretsch: And then we pair up that G and C, and we we can keep going pairing up that U and A and you this A and U and this C and G, and you can see, we have a nice ladder of pairs now.

Rachael Kretsch: But then we get to a G and an A. Rachael Kretsch: Those don't like pairing up, which is absolutely fine because RNA doesn't mind being unpaired it prefers being paired but it's fine being unpaired.

Rachael Kretsch: So now we have what we call a stem which is this latter base pairs and then the loop, which is this unpaired region so let's look at the frame shift element, or the FST.

Rachael Kretsch: So we're going to start where the ribosome is bound so it's here and we have on on paired region Okay, so it doesn't have any pairs and remember the, the ribosome is pulling the RNA through it to translate.

Rachael Kretsch: And a quarter of the time, this is where it slips. Rachael Kretsch: So what is it trying to pull out first for the ribosome was first going to try to pull this Green stem here, which has that blue loop.

Rachael Kretsch: Then we have an orange them with that black loop.

Rachael Kretsch: followed by a pink region that's not paired. Rachael Kretsch: And then we have the end of the FST.

Rachael Kretsch: Now, did you notice how I colored these both blue. Rachael Kretsch: Well it's because they can actually pair together So you see, we have G and C G and C G and CGUA.

Rachael Kretsch: And now I said RNA is fine being unfair, but it prefers to be paired so what happens is it pairs up this loop, is no longer a loop, it becomes a stem.

Rachael Kretsch: And when this happens when a loop becomes a stem we call it knot like, so the fec is kind of like a knot.

Rachael Kretsch: Now, why does this matter well the ribosome is translating pooling through the RNA and you can imagine if you're trying to pull something that's not quite a nod but not like you get more and more resistance, so this resistance may cause it to pause and then slip.

Rachael Kretsch: So how could we think about stopping it from slipping well what if we get rid of the knot, right So what if we get rid of those base pairs.

Rachael Kretsch: How would we perhaps do that well what if we came up with a drug that really like binding this blue and pink region here, and that would leave this to be a loop and is much easier to pull.

Rachael Kretsch: Now this drug is completely hypothetical, but you can imagine it kind of like the coins for Mario right, so this region likes finding that drugs so much that the drug will bind and leave this to be easy to pull and therefore we get no more pausing and no more slipping.

Rachael Kretsch: All right, well let's learn a little bit more by going into the 3D structure.

Rachael Kretsch: So the basics of 3D structure is just on this stem now if you notice before I said it was called a stem or helix and that's because of what it looks like in 3D.

Rachael Kretsch: So we have a ladder of pairs right, but in 3D that ladder is not a straight ladder it's like a winding staircase so or a helix you can see the pairs and they're going around and a helix and the loop is simply this region up top.

Rachael Kretsch: Now. Rachael Kretsch: We don't actually see each of the basis when we look at our Cryo-EM data, so we actually just see the shape when we are looking at Cyro-EM.

Rachael Kretsch: So this is the shape, we see you can still see kind of looks like a helix right a little staircase going around.

Rachael Kretsch: But one of the challenges when we're working with Cryo-EM is the question of how do we fit these bases and this general shape right, so we use Cryo-EM them to get the shape, but then we still have the problem of how do these bases fit in that shape.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so let's focus on how we get the shape, first of all, and that's really done through Cryo-EM right now at least that's what we do at SLAC.

Rachael Kretsch: And why is this so revolutionary well, I think it becomes obvious when we look at the past of structural biology.

Rachael Kretsch: So structural biology has managed to solve 160,000 protein structures right huge amount of protein structures, how good, are you with RNA.

Rachael Kretsch: While we're around 100 times less structure solves for RNA right, and this is due to many challenges with traditional techniques, but it is our hope that Cryo-EM can help us solve these RNA structures, unlike other past techniques.

Rachael Kretsch: So here's a review of what Cryo-EM means we have our RNA in this case suspended and ice here to remember the RNA sometimes pointed up sometimes down to the side.

Rachael Kretsch: We have electrons that come through our sample to make a 2d image, on the other side, and some of the views are top few side views bottom views.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we take all of these images and archives often millions of images and we ask a computer algorithm to reconstruct the 3D volume from these 2d images.

Rachael Kretsch: And why do we think it's so promising to use the technology well i'm going to give two main reasons, first of all it's in water right.

Rachael Kretsch: And why is that so special well before we used to have to make crystals of our RNA and all a crystal is is pretty much a densely packed RNA so we have all of our rnas pack densely into this crystal.

Rachael Kretsch: And it just doesn't really like being packed that way, so it took a lot of effort and time to get good crystals.

Rachael Kretsch: The second reason for water is it's closer to the cell like environment than a crystal would be I see closer right because it's just floating on and water it's not the crowded environment of the cell and, hopefully, maybe years down the line, will be able to actually image in the cell.

Rachael Kretsch: And the second reason is it's faster, so I can get more data quicker for different rnas.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's look at some structures that were solved, so this is work done in 2020 that lead it and you can see, they solved a variety of RNA so they really show that Cryo-EM.

Rachael Kretsch: was capable of solving the shape of many, many rnas so in grey is the shape so that's the RNA the Cryo-EM data is in Gray, and then colored is what we think the base positions are So where do we think these bases go in the shape that we got from Cryo-EM.

Rachael Kretsch: So you can see, we have many different types of shapes this one, for example, was designed to be closed pin like shaped, and this was actually the smallest shape that was solved by Cryo-EM at that time.

Rachael Kretsch: And why do I point that out well size is a huge limiting factor for Cryo-EM.

Rachael Kretsch: So, remember, as we were zooming in how small RNA yes, well, even at the hundred thousand times magnification that our microscopes allow us to see at our RNA still look like tiny dots, and so this was the smallest RNA previously solved and the FSC while we're interested in solving.

Rachael Kretsch: Is five seventh the size of that so it's even smaller So this was going to be a huge challenge.

Rachael Kretsch: But the team at the DAS lab and the Chui labs where we're up for the challenge, I want to show you guys the raw data, so this is what the image out of the microscope looks like.

Rachael Kretsch: And we have circled the RNA so they're really you know tiny dots you can see, we don't have much detail when we zoom in.

Rachael Kretsch: But if we collect millions of these images and average them, we can start getting more detailed pictures, so you can start seeing the shape in these 2d images.

Rachael Kretsch: And with enough data we can start to reconstruct the 3ds shape and here it is this is the 3D shape of the FSC, so this is what the ribosomes trying to pull out.

Rachael Kretsch: And you can see, we pointed out a hole right we're not really sure if that hole what that hole is and but I really want to focus in on this region, right here.

Rachael Kretsch: And if we turn ourselves 90 degrees we looking at it here, and can you guys see how that's kind of that staircase or that helical shape.

Rachael Kretsch: So this is a clear stem so we just have a stem and then a loop at the end here, and if we turn at 90 degrees again, and you can still see that he, like all like shape.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's try to model in our bases now where did the basis go in this shape, so we have the shape, but we also have the secondary structure we went through before right, so we have where what how many stems we have.

Rachael Kretsch: And you notice how we have one clear stem jetting out here, well, we also have a stem jetting out here right so that's, in fact, our orange stem over here.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we use a bunch of computational modeling techniques to fit in our RNA basis and here's how they fit it, so we have our orange them jetting out here, and then we have the Green and the blue stem that caused that lot knot like structure.

Rachael Kretsch: Just stacked on top of each other here, and then we have the pink connecting these two.

Rachael Kretsch: So okay great shape, what does it actually mean right structures don't tell us enough, we need to study them more.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's look at a video to see this shape, so you can see, as we turn it around you can see the shape now we're going to this is where the ribosome is pulling, it is this Green helix, then we have this orange helix, then we have the pink and the blue.

Rachael Kretsch: And now you see how the basis don't fit perfectly into the shape so we're a little uncertain and what the shape is so that's just showing you that we have 10 different possibilities of how the basis may fit into this cryo-EM shape.

Rachael Kretsch: And now we're going to remove the part that the Cryo-EM is pulling on next and draw it back in.

Rachael Kretsch: So did you notice how, when we drew back in it was right between the pink and the green or threaded through the pink and the Green parts of the RNA.

Rachael Kretsch: we're going to look at that, in a little more detail now so i'm going to color the part that the aren't the ribosome is going to pull next in red.

Rachael Kretsch: So the ribosome is trying to pull on that red strand, so it can translate it.

Rachael Kretsch: Right let's zoom in to see this more clearly, so the red, is what the ribosome is going to translate next so it's trying to pull it into the ribosome and you see how it has to go in between the Green and the pink.

Rachael Kretsch: All right, let's watch the video one more time so we're going to remove the part that the ribosome is pulling on next and then we're going to model it back in and you see how it threaded through the pink and the Green parts of the RNA

Rachael Kretsch: Yes, one more time we remove it now, we can see where it goes it's going to thread directly through the pink and the green.

Rachael Kretsch: Okay, great it's threaded through the pink and the Green strings, why does that matter.

Rachael Kretsch: Well let's think about how the other option, the other threaded option, so if we zoom in we see the threaded again.

Rachael Kretsch: It has to go through the pink and the Green parts of the RNA the only threaded it just goes around them.

Rachael Kretsch: Right and while that matter, well, it has to go through these are days it's going to get more resistance right as it's pulling it through so maybe that causes it to stop and then slip.

Rachael Kretsch: Whereas in this case, it has less resistance, because it doesn't have to go through or thread through so maybe that lets it just continue normally and read normally.

Rachael Kretsch: Now, one thing I want to note here is, we did not see this, so this is just a hypothetical structure, this is the structure we saw right.

Rachael Kretsch: Okay, so. Rachael Kretsch: We have a hypothesis of how it may work could we design a drug, to stop it working well, what if I put a drug here in this hole that kind of acted like a glue to keep it threaded so to make that resistance one more pooling even harder.

Rachael Kretsch: And that would cause it to slip even more. Rachael Kretsch: right because it's even harder to pull so that may be a drug that could work again just a hypothetical drug.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so we have that information and i'm telling you a lot of ideas about how we think the right zoom works with it, but remember how, on the grid that was just RNA and salty water right there was no ribosome, so we really want to know how the ribisome interacts with FC.

Rachael Kretsch: So what that means is instead of just having RNA and salty water, we need to add ribosome into the mix and luckily teams from Zurich and the UK.

Rachael Kretsch: Did this study and published in 2021 and science. Rachael Kretsch: Using Cryo-EM with the mixture of ribosomes and this part of the RNA to reveal this interaction and this is what the interaction looks like so in grey here we have ribosome remember the represents this huge machine, so it goes off of this picture as well.

Rachael Kretsch: And it's currently translating the RNA, so this is a coronavirus RNA it's currently translating but we captured it when it's paused so it's it's paused and translating right now.

Rachael Kretsch: And this is the FSC so it pauses right on where it's supposed to slip right.

Rachael Kretsch: And let's compare our structures, so we have the orange stem here the orange them also jumps out when the FTC is interacting the ribosome, we also have the green and blue stacked on top of each other very similar.

Rachael Kretsch: And then, finally, we have this pink region which connects the orange and the blue.

Rachael Kretsch: So we have very similar structures in fact this structure is also not like.

Rachael Kretsch: And it's also a threaded FST and i'm just going to show you that threading so the ribosome is pulling here and it's actually actively pulling in this case right because the ribosome is there.

Rachael Kretsch: And we know the ribosome has passed it because that's the ribosome is physically in in our images now.

Rachael Kretsch: So let's just color the string rat again, the one that the ribosome is trying to pull on next, and if we zoom in, we can see it's threaded through again, so we have the Green and we have the pink and the red is threaded through and the ribosome is trying to pull out that structure.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so we go back to our threaded threaded examples, so now we have two images of the frc one from our groups of just the FCC and then one from group sincerity and the UK.

Rachael Kretsch: Of the FCC on a paused ribosome and both of them are this not like threaded structure right, so we have more support for thinking that this threatening or not like structure causes pausing and that's slipping.

Rachael Kretsch: Now we don't have further support for this hypothesis, but we haven't rolled it out, either.

Rachael Kretsch: So, how does this all pan out with the drug I hypothesize so I said what if we bind a drug here that acts as a glue to make it even harder to pull the read through the rabbit zone.

Rachael Kretsch: Well, if we look at that position in the structure on the ribosome so i've just rotated the image, we can see that hole still exists, so we still have a hole lot of drug may fit in.

Rachael Kretsch: So it's a potential target and that's what we like having structures for to inform these potential targets.

Rachael Kretsch: All right, let's watch a concluding video to see this in action, so we have the coronavirus RNA here in orange.

Rachael Kretsch: that's where the ribosome slips a quarter of the time and then this is the knot the RNA structure that we're really interested in there.

Rachael Kretsch: And in this case, it did not pause it could just read through and it reaches its stop.

Rachael Kretsch: and Rachael Kretsch: associates and has made it file proteins, but one RNA gets translated many different times so now the knot is going to reform.

Rachael Kretsch: And another episode is going to come along making more viral proteins and this time the ribosome is going to pause and slip back so this will happen, a quarter of the time, roughly.

Rachael Kretsch: And now it's reading completely different proteins, so it continues on reading these blue proteins until it reaches its own stop saying no down the line.

Rachael Kretsch: And that's how we think perhaps the RNA structure this not like threaded structure.

Rachael Kretsch: will cause the ribosome to slip sometimes by making it harder for to pull.

Rachael Kretsch: So hopefully today you've learned what structural biology is and how we think about it.

Rachael Kretsch: you've learned what RNA viruses are you've learned that there's four levels of RNA structure and each give more and more information.

Rachael Kretsch: you've learned how we use these Cryo electron microscopes to study 3D structure.

Rachael Kretsch: And then finally you've learned how we think about what these structures could tell us about practices.

Rachael Kretsch: And our key takeaways well RNA viruses are still a huge challenge to human health, but we hope structural biology will offer clues on first of all how they work and then secondly, how we can stop them working.

Rachael Kretsch: And decades of technological development and basic science have enabled our current response, and we hope our basic science work on RNA structure will enable future responses to disease.

Rachael Kretsch: So RNA is the key component, or I can component or any viruses, but its structure has remained hard to see.

Rachael Kretsch: So we're working on developing the basic science through Cryo-EM to enable these revolutionary views of RNA and the hopes that we can learn about file rnas and how to stop them working.

Rachael Kretsch: So, looking to the future, we have many goals that i'll just list for here.

Rachael Kretsch: The first is to get higher resolution, for all that means is more detailed shapes.

Rachael Kretsch: Which means we're going to be more confident and where all the bases are so if we have more detailed shapes we can better fit in where all the bases should go.

Rachael Kretsch: The second is the fact that RNA can change shape right So when I was talking about Oh, maybe there's an m threaded RNA well that's a different shape, so we hope in the future, we can see different shapes.

Rachael Kretsch: Third, we hope to see how RNA interacts with proteins and drugs.

Rachael Kretsch: And that could also be an avenue, and then, in general we just want more structures and how they're linked to how RNA works, and this is beyond SARS-cov-2 to to other viruses, as well as beyond viruses, because our needs and all living things.

Rachael Kretsch: Alright, so here's the Community and special highlight to Zhouming, Kaiming, Banya, Kelly and Rachel who lead some of the work I was talking about today.

Rachael Kretsch: And then here's a list of people in the Community, so we have the Chui lab and the DAS lab which has had many mentors for me learning how to study RNA and how to use carrion.

Rachael Kretsch: We have passed to DAS lab Members as well as other collaborators that have contributed to the work of RNA cryoEM.

Rachael Kretsch: We have the great team at SLAC and mostly the communications department that organizes these wonderful lectures, so that we can share a science to the Community broadly.

Rachael Kretsch: And then, finally, we have our two panelists who we're about to hear from Jonesy and Miri, who are great RNA scientists and I.

Rachael Kretsch: You guys are very lucky to be able to hear about their science and that's what we're going to move to next so i'm going to stop sharing my screen and we are going to start the panel discussion.

michael peskin: Okay well Rachel Thank you very much, there there's a lot of unexpected detail in this lecture, I must say i've learned a lot about this RNA biology by interacting with you, so I hope other people find that equally fascinating.

michael peskin: um you've introduced the two panelists, Miri and Jonesy, Jonesy can you turn on your video.

michael peskin: you're there somewhere. michael peskin: Actually physically you're in Munich so.

michael peskin: But nevertheless, thank you very much for being here and let's now start with the questions so.

michael peskin: Stephen would like to know um. michael peskin: Is there a problem that the salt solution that you shake up the RNA and will change it shape.

michael peskin: And I guess also Rachel talked about the crystallization if it's one better than the other what's what's the deal here.

Rachael Kretsch: yeah so i'll try to answer that and Mary or jonesy feel free to come in, after um so first salt and salt, is very important for earn a structure so actually many rnas will not form their structure if there's no salt around.

Rachael Kretsch: So varying the salt concentration is actually something very interesting and could potentially change the shape or the range of shapes that the RNA can form as for kind of crystallization versus using this frozen sample.

Rachael Kretsch: They all all techniques have their artifacts right so we're not imaging things perfectly in the natural living cell right, so I wouldn't say one is better than the other.

Rachael Kretsch: They could give different results. Rachael Kretsch: But it doesn't mean one is better than the other, quite frankly, it's just easier to get the RNA on the grid and to crystallize it.

michael peskin: Okay um are you worried that this electron beam that you're using to make the image is going to destroy or deform the RNAs.

michael peskin: You have control over that. Rachael Kretsch: And it does.

Rachael Kretsch: It definitely destroys the RNA so that's a factor, we have to be very careful about.

Rachael Kretsch: So we call this what we call radiation damage. Rachael Kretsch: So electrons are pretty powerful things, especially when you're dealing with such small scales.

Rachael Kretsch: So if we put too much electron dose we will damage RNA completely so we try to limit the amount of electrons we expose our sample to and that's also why you saw so much noise and those raw images right they weren't clear at all.

Rachael Kretsch: If we had expose it to more electrons and there was no damage we'd see much clearer images, but we simply can't do that without damaging the RNA

michael peskin: Maybe you need more sensitive detectors of course that's something also that we do here.

Rachael Kretsch: yeah and detectors. Rachael Kretsch: i'd say a lot of the current improvements that we've seen in CryoEM over you know the past 10 years or so, have been because of improvements in detectors.

Rachael Kretsch: So now we're able to more sensitively detect individually digital electrons as they pass through a sample.

Rachael Kretsch: And certainly improvement style allow us to do that faster and with less electrons will help and that so there's many people working on that I don't work on that personally that I can only hope they'll give us much better detectors in the future.

michael peskin: Okay i'm Fred would like to know um.

michael peskin: do the RNA get oriented in this in this setup um he he interprets What you said is saying that you make 2d images which then are combined to make a 3D.

michael peskin: So um do you actually see the various turns or rotations of the molecule are they are they specific orientations that you see, and maybe you can say a little more about how you put the picture together to get a real 3D.

Rachael Kretsch: Okay, so i'll start. Rachael Kretsch: With you know what are these orientations do I get to decide them.

Rachael Kretsch: And the answer is no, I don't get to decide how the molecules all fall, so you can think about it, as you know, my rnas are all in water and they're just all tumbling around randomly.

Rachael Kretsch: And then I very quickly put into this very cold liquid ethane so they all just freeze in place, however, they were tumbling right so they're all kind of just randomly orientate it in my eyes.

Rachael Kretsch: So I have all orientations. Rachael Kretsch: In my eyes.

Rachael Kretsch: And then, when I image them it's just like when you. Rachael Kretsch: Look at an object right you only see one 2d view so we see there the top the bottom, the side, depending on the random way it was frozen.

Rachael Kretsch: And then we use computer algorithms to reconstruct that so the computer takes in and it estimates Okay, well, I think this image was from the top.

Rachael Kretsch: So now we know what the top should look like and this image was from the side, so now we kind of know what the site looks like and it does that, for all the different images and all the orientations and tell it has a full picture of what the whole shape should look like.

Rachael Kretsch: I don't know if any of Miri her Jonesy just went away have anything to add on on the orientation side of things.

Miri Krupkin: um yeah I can say that everything you said was correct, and you can kind of think about it, like if you go into nature and you take a picture of a bird you can always ask it to be oriented.

Miri Krupkin: The way you would like it to be oriented and let's say you want to build a 3D model of the bird you'll have to collect many, many, many pictures of the birds, so that you see from all directions.

Miri Krupkin: And then, perhaps, change the sample preparation, so the way that if you want to get a different picture of the bird maybe instead of sitting under the tree you'll see like a day.

Miri Krupkin: window and then you'll be I level with a bird you can kind of change the sample preparation.

Miri Krupkin: The timing that you take for freezing the salt concentrations as other people mentioned the ice thickness and kind of.

Miri Krupkin: playing tricks that we've learned to do to kind of try and help orient molecules in different ways, but yeah it's a sometimes a big problem for molecules that.

Miri Krupkin: Are symmetrical and have a preferred orientation, so we kind of always see them kind of like this, but maybe we're interested to see what's going on on the side.

Rachael Kretsch: yeah so just add to that i'm i'm incredibly lucky that I do things that are very small and often globular.

Rachael Kretsch: So they don't have a preferred orientation right, so what Miri is talking about is imagine if you have something that's very pointy and it prefers to be pointed up.

Rachael Kretsch: Instead of sideways right so i'm lucky in my case for my samples I don't have that, but many, many people during Cryo-EM often have that problem, so I was great to add me.

michael peskin: Okay um let's pursue that a little so you should these pictures that you're British colleagues took the the RNA actually embedded in a ribosome.

michael peskin: So when you use a big structure like that you get presumably fewer images and oriented, could you just describe the relative difficulty of seeing the the RNA in situ and free in a solution.

Rachael Kretsch: yeah and so, if we're comparing you know imaging a ribosome imaging a tiny little RNA there's a lot of factors that are different, so one is the preferred orientation right the larger, it is the more asymmetrical it is, the more likely it's going to prefer to be one way or the other.

Rachael Kretsch: The other factor is how easy it is to know what your view is so if you have something very small and noisy it's gonna be hard to figure out whether it's a top aside or a bottom view.

Rachael Kretsch: And that's the problem we have with smaller and is is actually figuring out how is that particle oriented right, whereas something as big as the ribosome, it's often much easier to see and figure out if it's a top side bottom view so we can much more easily correctly.

Rachael Kretsch: assign the view when we're reconstructing the 3D. Rachael Kretsch: shape for something larger.

Rachael Kretsch: So that's The second factor, so we have you know we may have more preferred orientation, but it's much easier to to guess what the orientation for each images.

michael peskin: You want to comment on this. michael peskin: Okay let's move on to a different subject now Anthony would like to know how big a frame shift can happen, is it really just you shift by one or two base pairs or can you have larger frame shifts.

Rachael Kretsch: As an interesting question so all the ones I know of are either minus one so move one or plus ones and move forward one I don't know if jonesy or Miri has heard of other scenarios of Frame shifting in nature.

Rachael Kretsch: Maybe all that we know. Rachael Kretsch: About biology, we may simply not have discovered it yet right and not saying it's impossible.

Rachael Kretsch: But we just don't know about any. michael peskin: One let's see that this idea of a frame shift was really novel and mysterious to me and Gordon had a question i'm going to read what he said and then interpreted.

michael peskin: He said it wasn't clear to me if the slippage is necessary in viral protein production or whether it is an exploitable defect.

michael peskin: And maybe you should comment in on that, but there's a more general question, which is why should there be frame shifts I mean in human DNA the proteins are laid out with all this like dark matter between them.

michael peskin: Why does the virus form itself in this way, presumably, it has some evolutionary advantage all right, what is that.

Rachael Kretsch: Okay, so I can I can give a shot at this and I think Miri may also be able to get a shot at it.

Rachael Kretsch: So viruses are quite different from humans right we they only have like 30,000 bases that's their whole genome right humans billions of these.

Rachael Kretsch: Okay, so we're doing if they're a small scale, and the reason they're so small is they have to package, the full genome into this little virus that then has to travel around and spread from human to human accent.

Rachael Kretsch: Right so by having one part of the RNA sequence code for two proteins, they are blue to code for more proteins in a smaller genome.

Rachael Kretsch: which, in theory, can can help them propagate more now, as I think Gordon said in his question.

Rachael Kretsch: That makes it exploitable right it's it's something that if we mess, with it, if we make it slip too frequently or not enough.

Rachael Kretsch: Now the viral proteins are all made in different concentrations they we have different amounts of viral proteins and the virus just doesn't function as well anymore.

Rachael Kretsch: So that's kind of our aim in learning more about how frame shifting works to try to stop it and use it to to harm the viruses.

michael peskin: And Miri do you want to add something to. Miri Krupkin: Everything that Rachael said and.

Miri Krupkin: same when you have a frame shift the virus can exploit it to make different proteins at different ratios, for example, there might be a protein that it needs a lot of and some other protein that it needs only a few so you can make the frame shift.

Miri Krupkin: Last frequent and then you can play with different ratios and build different structures and different machinery that is required for the virus to survive.

Miri Krupkin: And then the other point is as Rachel said the viral genome, are very small compared to, for example, human genomes and I study HIV, which has an even smaller genome than tSARS-Cov-2 it has only 9000.

Miri Krupkin: basis, and this way it's able to use just one MRNA in a that it's making and then it can frame shift when needed.

michael peskin: So HIV really uses this mechanism of producing a lot of something in a little with something else better interesting.

Miri Krupkin: Yes, the ratio is very important for HIV.

michael peskin: Other comments on this question Jen see you went away. Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: No, I agree with Rachel and Miri, their spot on with that so.

michael peskin: Okay um. michael peskin: there's one more set of questions i'm sorry go ahead. Miri Krupkin: I kind of want to refer to an earlier question by Anthony has how big can a frame shift be I wanted to mention that there is also other kinds of events that are not a frame shift.

Miri Krupkin: With RNA can cause and those can be much larger they could sometimes be like 100 basis long, for example in the process where RNA is being copied to DNA in the HIV virus.

Miri Krupkin: There, a event of templates switching were they in HIV case that enzyme not the ribosome a different enzyme called reverse transcriptase can jump very long distances from the site that it was into a different site.

Miri Krupkin: and also in Sars-COV-2 to there is also events or a template switching where the enzyme that's copying the irony is actually jumping and sometimes 100 sometimes 1000 bases difference.

michael peskin: But actually i've got asked you are those 1000 basis or 100 basis along the chain but maybe they're near to each other in space and you could learn about that, with this method.

Miri Krupkin: that's a great question and that's exactly what i'm looking into and also other people that are studying this template is switching event.

Miri Krupkin: And we're looking into how the RNA structure can regulate this kind of transfers that when you look only at the 2D sequence, it may look very far away, but when everything is folded kind of brings those split those.

Miri Krupkin: Areas right next to each other, so this kind of 3D movie puzzle can come together and aid to the enzyme to transfer from this spot was into the new spot.

michael peskin: Very cool. Rachael Kretsch: I think I just want to add to that so you know how we were looking at this, it was only at basis.

Rachael Kretsch: So we could see the 3D structure of that but to study the the things that Miri is talking about right now what we would want is to be able to image, the full genome right, that would be the ideal.

Rachael Kretsch: Right now, our technology is not there, right now, we can only you know image things that are compact and fold up.

Rachael Kretsch: But that would be what we want to get to is really being able to see how the full genome looks like in 3D space and maybe these regions are in fact close together so hopefully Cryo-EM will be our route to that path.

Rachael Kretsch: And we'll see. michael peskin: Okay, very interesting there's one more issue that's in the questions, so let me ask you about that.

michael peskin: With proteins, we now we've been imaging proteins for 17 years with X Ray structures.

michael peskin: And so there's a lot of experience, a lot of data, and now there are new computer algorithms like one called alpha fold.

michael peskin: That are pretty good at predicting the structure from the sequence, where are we in that with RNA is it intrinsically more difficult, and when we're going to get there, where we can just take the sequence, and by computation instead of by experiment, a learn about its structure.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: Take a stab at. Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: So I would first start and say that there are a couple of programs out there that just based off of like thermodynamics and.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: Minimum energies are able to actually fold RNA and generate predictive tertiary structural models, one is like RNA composer, for example.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: And this is something that you know you can just take a secondary or primary sequence, and even.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: details about the secondary structure from like different various experiments that may be carried out in the lab and generate a tertiary structure, I think, was interesting about alpha fold.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: And this was something that Rachel mentioned in her talk, there are about 160,000 protein structures that exist for you know, proteins and for RNA you know there's only about 1600.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: And alpha fold is generated, because we have so much data, you know about different proteins that we're able to actually you know generate these these more accurate models and and development well yeah develop models to basically.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: get a sense of what protein looks like, and I think, in the absence of data, because we don't have so much data about RNA it's more difficult.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: or just not quite there yet I wouldn't actually even say it's difficult if you don't have data it's kind of hard to actually like.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: generate a model, but I think, with more time and with more approaches, where we're able to actually experimentally determine structures of.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: Of RNA we're actually able to build that library or build that database of structures to develop something that's more similar to alpha fold to improve the accuracy.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: Of modeling tertiary structures, like without having to use CryoEM and X Ray crystallography, so I think a few more maybe another decade, maybe not not not so far, but maybe five to 10 years or so maybe we'll hit that hit the optical stage with the RNA.

interesting. Rachael Kretsch: I think that's the goal for for a lot of us during our newest.

Rachael Kretsch: Like you know we'd be happy if we had that predictor we just don't yet that's why we're trying to solve more and more structured and I just want to add on when you said Oh, it may not be more difficult there's a lot of people that think it's actually an easier problem.

Rachael Kretsch: And one of the you know basic reasons for that is remember how proteins have 20 building blocks.

Rachael Kretsch: Well RNA only has four building blocks right so actually we have a lot less possibilities of how we can build our RNA compared to when we have 20 options right.

Rachael Kretsch: So our kind of our search space is searching for the structure is a little smaller does that make it easier and we don't know yet because we don't have the data to actually try.

Rachael Kretsch: But it could make it easier perhaps. michael peskin: Okay, and. michael peskin: easier, also to learn how to fight these things.

Rachael Kretsch: yeah exactly once we know the shared we can think of ideas of how to fight it right so.

Alisha 'Jonesy' Jones: Exactly yeah. michael peskin: Okay wow this has really been a fascinating discussion Thank you all very much we really appreciate your insights and I hope people out there have learned a lot um we'll have another one of these SLAC public lectures at the end of May that will be on a very different subject.

michael peskin: Using quantum devices to explore the universe, and so I hope you folks will all come back then meanwhile let's thank Rachel and Miri and Jonesy and.

michael peskin: we'll see you all next time. bye.