michael peskin: So I would like to welcome all of you to the next edition of the SLAC public lectures, thank you very much for coming.

michael peskin: We are looking forward to having these lectures back in the panofsky auditorium at the SLAC site, but um please excuse me, the pandemic is what it is so we're still remote and we thank you very much for taking time out of your busy home schedule to be here.

michael peskin: The lecture today is going to be very interesting it's about how to leave transistors in the dust and a vision for new ways to do functional computing.

michael peskin: The lecture is Aaron Lindenberg, who is a professor, both on campus in the department of material science and engineering and a professor at Slac in our department of photon science.

michael peskin: Um Aaron is. michael peskin: A very distinguished person in this field, a long time ago he made a lot of waves, by taking photographs of ultrafast Pico second motion of individual atoms and various materials.

michael peskin: He got his PhD from Berkeley on the basis of that work he was briefly a faculty Member at Berkeley but then he came over to our side of the bay and here he's been making waves, also in trying to understand the details of various exotic materials, some of which he'll tell you about today.

michael peskin: um he is has a Department of Energy outstanding mentor award and has a very active group here at slac and using our facilities.

michael peskin: At the end of the lecture there will be a question and answer session, so please if you'd like to hear a further discussion and then at the points of this lecture.

michael peskin: Please give us your question, you can ask a question by looking at the bottom of your zoom screen there's a Q&a box.

michael peskin: And if you would write that question into the Q&a we will go through these one after another and ask.

michael peskin: Aaron and a couple of his colleagues who are here about your questions, but right now let's just to get on to the matter at hand Aaron please take it over and tell us about the next the next stage in building computing brains.

Aaron Lindenberg: All right, great Thank you very much, Michael it's it's a real great pleasure to be here today.

Aaron Lindenberg: So I want to tell you about a journey that we that I think we've really just begun in many ways, I feel like.

Aaron Lindenberg: we've just scratched the surface of this work and and as it, as in many good experiments we finish an experiment and oftentimes there are more questions than answers.

Aaron Lindenberg: But nevertheless i'll give you my view on on on where we are and and some of the some some of the I think very exciting first work that we've carried out here at slac.

Aaron Lindenberg: So i'll be talking today about new ways of probing materials and devices, as they function as they operate.

Aaron Lindenberg: And this means looking at the atomic scale and in real time and it turns out that these processes occur on unimaginably short length scales, corresponding to the distance between atoms.

Aaron Lindenberg: And also unimaginably short timescales timescales will be talking about the order of Pico seconds, which is roughly 1,000th of 1,000,000,000th of a second so.

Aaron Lindenberg: These are unimaginably short time scales, and yet it turns out that processes occurring on these types of timescales really determine the functionality and determine how these types of devices work.

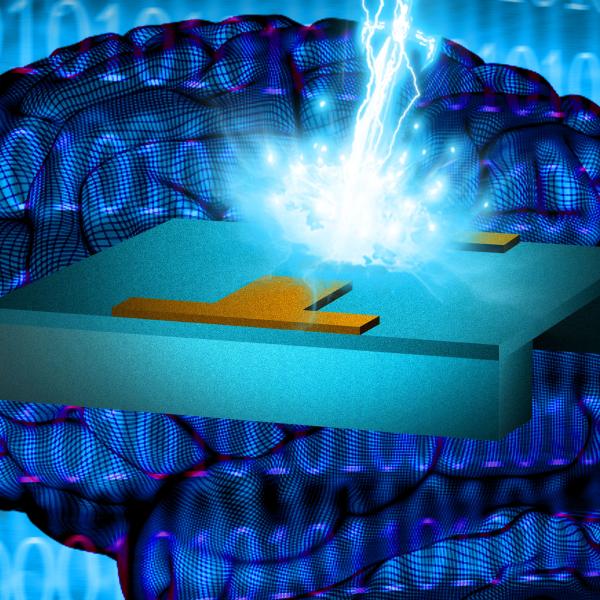

Aaron Lindenberg: And i'll be talking in particular today about a really I think new class of devices which are.

Aaron Lindenberg: Really motivated and closely connected to the way your brain works and so we'll be talking about ways of what people are now calling brain inspired computing as a means of of trying to.

Aaron Lindenberg: Create devices and materials, which in some way mimic the functionality of the brain so without further ado, we should get started, I want to encourage you, as Michael just said.

Aaron Lindenberg: To ask lots of questions I tried to make this talk as as general as possible i'm hope i'm hoping they're a bunch of kids out there who are listening and so no stupid questions i'm looking forward, in particular, to the question and answer session at the end of this talk.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so i'm just start out with I wanted to tell you a little bit about myself. Aaron Lindenberg: And so, so, as I mentioned, I hope, there are some kids out there, so I, the first thing I was asking myself when I was trying to make this talk was well when how old was I when I first got interested in science.

Aaron Lindenberg: So on the on on the over here on the on the left. Aaron Lindenberg: Is a picture of me I think i'm about 12 years old there, and certainly at that time I could say I probably wasn't that interested in science, I had sort of the natural curiosity that that lots of kids have.

Aaron Lindenberg: But certainly I didn't know I wanted to grow up to be a scientist or Professor or anything like that. Aaron Lindenberg: But I was interested in I had certain hobbies and one of them was juggling and i'm bringing that up in particular here, because when you think about watching an amazing juggler think about the balls moving on an amazingly complex trajectory.

Aaron Lindenberg: You know unbelievably fast, and you know what you'd like to do if you want to learn how to juggle that yourself.

Aaron Lindenberg: you'd like to maybe you know take some stop action photographs like to freeze the motion and slow it down so that you could start to learn it yourself.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so the things that i'll be talking about today in many ways are kind of built on that idea, except instead of talking about juggling balls moving through space we're going to be talking about Atoms moving on really.

Aaron Lindenberg: Short length skills and really fast time skills okay now we're going to try to find ways of really seeing and watch what they do and visualize what they do.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so, then I got older and so then that's me on the right at Berkeley as a Grad student taking some some experiments with this was one of the early days of kind of what what we call ultra fast X Ray science and.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so today i'm going to kind of tell you a little bit about where we are now it's been more than more than 20 years since then and it's quite amazing to think how far we've we've come, I think.

Aaron Lindenberg: Alright, so um one more sort of just sort of general item of kind of motivation and also a little bit about myself.

Aaron Lindenberg: So music is something that's been really important to me, for it for a really long time this is one of my favorite piano pieces.

Aaron Lindenberg: it's an Etude from from Chopin, and if you haven't heard it then I definitely encourage you to go out and listen to it.

Aaron Lindenberg: But, but in part i'm also mentioning this because we think about a musical score, of course, there are many notes on this page.

Aaron Lindenberg: If you think about first of all, just playing all of the notes at once well this certainly wouldn't sound very good right, and so the part of the.

Aaron Lindenberg: Some of the central aspects of music involve timing involved the placement of notes and and you need to play the notes in the right order with the right dynamic and the right beat and so on.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so, so this this aspect of of kind of dynamics, I think, is something that is really all around us and and involves many aspects of our lives.

Aaron Lindenberg: So um. Aaron Lindenberg: Let me give sort of a very kind of brief kind of motivation of what i'll be talking about today so.

Aaron Lindenberg: As I mentioned we're going to be talking about new types of electronic devices and switches.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so I think you're probably many of you are probably aware that the computers that you use and the phones that you use are all built upon this kind of really magic electronic device called the transistor.

Aaron Lindenberg: This was this was invented first in 1947 and the you know the very first transistor look something like this.

Aaron Lindenberg: It was this giant macroscopic kind of device at its heart, a transistor is an electronic switch so you think about a.

Aaron Lindenberg: it's essentially it's got three inputs or three outputs and at the bottom here over here.

Aaron Lindenberg: This is the the what that the base, this is the gate This is like a control Okay, and this control effectively controls the flow of electrons from one side of.

Aaron Lindenberg: The transistor to the other, and so it's this basic kind of switch this kind of electronic switch that forms the basis of all the kind of amazing kind of.

Aaron Lindenberg: processes that that one can depend upon nowadays within computers so as I, as I show in the picture there originally these transistors were really big and and, of course, when couldn't imagine.

Aaron Lindenberg: trying to find ways of of packing many of them together but probably many of you are also familiar familiar with moore's law.

Aaron Lindenberg: Certainly if you if you're from here, from Silicon Valley, this is played a central role in the development of.

Aaron Lindenberg: Silicon Valley and so on, and essentially what this says and in words, is that the density of transistors on a chip is doubling something like every couple of years, and so, if you think about the sort of exponential growth of of this process.

Aaron Lindenberg: there's What this means in terms of length scales is that people have found ways of shrinking transistors originally from that kind of bulky structure that I showed on the top there now to something.

Aaron Lindenberg: On the size of a DNA strand so the distance the diameter across from one end of this DNA strand to another is about one nanometer, a billionth of a meter.

Aaron Lindenberg: And people have really now found ways of compressing these transistors and and growing them now at the 10 nanometers length scale.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so it's this process it's this kind of doubling this this moore's law that has allowed for you know the amazing expansion of computing and and nowadays, you have millions and millions of transistors and some very small area on a chip.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so um but nevertheless it's also clear, and this is becoming more and more clear to too many people in the field that there's maybe some end in sight of moore's law as you shrink devices beyond the size of.

Aaron Lindenberg: A few nanometers many complicated effects turn on quantum mechanical effects occur and there are many kinds of kind of effects that that in the end.

Aaron Lindenberg: seem to imply that maybe we're not going to be able, just to continue shrinking transistors more and more and more, and then on top of that.

Aaron Lindenberg: When you think about computing nowadays, the energy costs associated with computing are really skyrocketing and i'll show you some numbers.

Aaron Lindenberg: In a minute, but nowadays, the energy costs just associated with with with computing represents large fractions of the of the total power usage of the world.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so it's, for this reason that many people have have been excited and started to think about new types of computing.

Aaron Lindenberg: Where it's not about using a transistor at all and it's about trying to think about ways of creating devices which are in some way in some ways mimic the way the neurons and synapses of your brain actually work.

Aaron Lindenberg: So this sounds pretty cool and i'm going to try to tell you a little bit about about how this field has developed and, in particular, some new ways we have a really watching these devices and and.

Aaron Lindenberg: starting to understand how these things actually work and the dynamics of them.

Aaron Lindenberg: This this is, you know really exciting for many perspectives for me it's exciting it's a merging of the fields of.

Aaron Lindenberg: The merging of many fields in science from computer science to biology material science nanoscience.

Aaron Lindenberg: And you know really represents kind of a new direction, I think. Aaron Lindenberg: And, and the key thing the key or one of the key kind of things that is really required to make these things work.

Aaron Lindenberg: To understand how these things actually function, you need ways of actually seeing these devices, as they function and, as I mentioned, this requires ways of watching these processes occur in real time.

Aaron Lindenberg: At the atomic scale, so I was trying to think of some way of kind of really kind of explaining this and in in simple words and so so here.

Aaron Lindenberg: over here, I have a picture of someone trying to solve a rubik's cube and so everyone knows solving a rubik's cube is a really complex endeavor right, but now.

Aaron Lindenberg: What What about if you tried to solve the rubik's cube blindfolded well, of course, you probably know, people can even do this, this gives you some idea of the power of the human brain and in.

Aaron Lindenberg: enabling these types of things, but the key point here is that when you're when you're blindfolded when you can't see these processes as they occur.

Aaron Lindenberg: it's much, much more difficult to understand things and nature is kind of an amazingly complex kind of thing.

Aaron Lindenberg: And, and so the more we can understand and really see how these devices actually the work, the more we can design better ones, the more we can.

Aaron Lindenberg: design new ones with higher efficiency and higher speed and so on.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so um, as I mentioned dynamics is is really all around us, so I was walking through Stanford campus a couple of months ago I don't know if you can read the sign on your screen.

Aaron Lindenberg: But it basically says, this was this was sort of a motivational sign to motivate the the football players practicing you're getting better or you're getting worse, you never stay the same right, and so this is maybe a.

Aaron Lindenberg: potentially a good way to live your life or a motivational kind of way of of of improving, but it also gets at this idea that that really the world is itself just intrinsically dynamic and, and this is something that I think we're all aware.

Aaron Lindenberg: There are many examples of this, as you start to zoom in in time and so on the left here i'm showing some famous photographs from Harry egerton.

Aaron Lindenberg: These are, these are photos using flash photography you know, in the very early days of.

Aaron Lindenberg: Stop action photography, and so what you can see here, for example, is a picture of a bullet passing through an apple or the very first steps that occur when a hammer strikes a glass bottle or on the bottom.

Aaron Lindenberg: This is, this is a someone dropping something into a glass of milk and so you start to see when you can.

Aaron Lindenberg: zoom in in time when you can start to see these processes that would normally be blurred out to the human eye, that you can start to see this amazing kind of complex processes and and by seeing these processes, you can then start to understand them better with.

Aaron Lindenberg: here's one more kind of interesting and cool example that that I think you might have noticed before if you've ever held an uncooked noodle.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so you might have noticed, if you ever hold an uncooked noodle at all it's this kind of rigid kind of object, when you try to break it.

Aaron Lindenberg: oftentimes the noodle doesn't break in in just a single spot as you might sort of not easily predict, in fact it breaks and in kind of multiple spots, and so what i'm showing here are images of.

Aaron Lindenberg: On millisecond timescales essentially stopped action photographs of the process that occurs when this noodle effectively breaks and you can see it's this amazingly complex process.

Aaron Lindenberg: You can see it breaking in two places, but you can also see waves bouncing back and forth from one end of the noodle to the other, and so this really capture some of the kind of amazing complexity that you start to see when you zoom in and time.

Aaron Lindenberg: But then, on top of this, it turns out that so not only is it powerful, to be able to see these things, but when you can zoom in and time you also.

Aaron Lindenberg: oftentimes find ways of engineering these properties and you oftentimes find ways of creating new types of interesting and functional properties so um.

Aaron Lindenberg: This next image here is now a picture, where instead of just breaking the noodle Okay, what we do is we just first apply a slight little twist about the long axis of the noodle.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so now there's a slight twist and then you break again, and you can see that, when you do this, you completely change the dynamics of.

Aaron Lindenberg: of how this noodle breaks, so this so that what this illustrates for me at least is. Aaron Lindenberg: Is that, as you start to zoom in and time on these types of processes you oftentimes find ways of engineering them and controlling them and creating new types of materials with interesting properties.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so we want to zoom in in space and, in time, and so, so what we're talking about here in some sense is a form of microscopy right and so here on this slide this is Gary larson's take on on.

Aaron Lindenberg: The very early microscope right, so this is, you know very large scale kind of microscopy we want to zoom in, and now we want to do this at the atomic scale okay and.

Aaron Lindenberg: On the scale that that separates one atom from another in the material and so can you do this.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so the way i'm going to try to describe to you now how we actually do these types of experiments and how we're able to really measure.

Aaron Lindenberg: The structure of the material and watch as the changes and the key thing that that the key process that we take advantage of and in in doing these things is a process that's.

Aaron Lindenberg: called the diffraction Okay, and the diffraction is really an interference phenomena in the in the end, and this is something that's that's again all around us, and all of us should be familiar with, and so.

Aaron Lindenberg: What you can see here is on the on the very far left corner of the screen i'm just showing two pictures of two types of waves were on the far left the to get we're adding.

Aaron Lindenberg: The Orange wave to the green wave, and you can see that the crest of one wave is aligned with the crest of the other wave and these then add together to form a larger way larger amplitude.

Aaron Lindenberg: Right, whereas if you go over one now what you can see is that, instead, if I just changed the relative timing of these two waves, the relative phase of these two waves.

Aaron Lindenberg: And I align them so that the crest of the green wave is aligned with the trough of the.

Aaron Lindenberg: Of the top orange wave, then, then, in that case, these things cancel out so on the left, this is called, this is an example of what's called constructive interference, the two waves are adding constructively together.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then on the right, this is an example of destructive interference and these types of processes are all around us in nature, as I mentioned.

Aaron Lindenberg: there's the example of what are oftentimes called rogue waves on the ocean, these are these oftentimes people don't really understand all of the origins of these.

Aaron Lindenberg: These involved involve the superposition oftentimes have two waves, which add together to form an extra large wave, which then of course can be.

Aaron Lindenberg: pretty important if you're sailing out on the ocean one of those come along. Aaron Lindenberg: Over over here, what we have is a picture of a concert hall and.

Aaron Lindenberg: If you've ever been to a concert hall, then I think you know that that the important the sound quality is something that is really important.

Aaron Lindenberg: And engineers when they design a concert hall they think really carefully about the shape of the room. Aaron Lindenberg: And they think about processes like traction and interference, they imagine the sound waves emanating from all the musical instruments down the stage bouncing off the walls.

Aaron Lindenberg: And you can imagine, this amazingly complex superposition of of the sound waves all bouncing in many directions and eventually ending up in your ear.

Aaron Lindenberg: Right, and so you have to really think about these types of processes in order to to design an acoustically nice musical sound hall.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then over here over here we have examples of. Aaron Lindenberg: Some things that that that I really just learned about recently.

Aaron Lindenberg: This is an example of a muffler which you've probably all seen on cars and it turns out that mufflers course their their main design is to reduce the sound that comes out of a car.

Aaron Lindenberg: And they take it, they do this in part by effectively creating the you have loud sounds coming from the engines.

Aaron Lindenberg: The sound waves bounce off of carefully engineered structures to overall create a destructive interference pattern and create such such that a person standing.

Aaron Lindenberg: at the back of the car doesn't here as loud as sound as they normally would and the same principle goes on and noise cancelling headphones and so.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so those are examples about water and sound waves, but the same type of processes also applied to light light is also a wave and here's a really beautiful example of of the diffraction and interference applied to this this amazing butterfly called the giant blue morpho butterfly.

Aaron Lindenberg: If you ever seen at the zoo the picture of this picture doesn't really capture all the beauty of this of this.

Aaron Lindenberg: Of this insect it's got this amazingly bright blue kind of tinge to it, and so you might think that this is just due to pigments in the.

Aaron Lindenberg: In the skin in the in the wings of the butterfly right oftentimes their materials which will absorb certain colors of light and.

Aaron Lindenberg: and emits other other colors but if that that's not what's happening here in the in the butterfly. Aaron Lindenberg: If you zoom in spatially and look at very short lane scales, the structure of this wing than what you see is this kind of these kind of periodic lines.

Aaron Lindenberg: oriented like this and then this these lines forum something called the diffraction gradiant. Aaron Lindenberg: and effectively light waves from the sun, the sun is admitting waves of many different colors the blue waves effectively scatter off of these these these.

Aaron Lindenberg: micron scale structures in the wing of the butterfly and they constructively interferes but blue part of the spectrum constructively interferes.

Aaron Lindenberg: And the end the wings look blue, whereas the red part of the spectrum effectively destructively interferes and so you see dominant the blue part of the of the scattered like.

Aaron Lindenberg: here's one more sort of just very simple example same sort of physics, the zoom in picture of the surface of the bubble right, and now you can see the you've probably all seen these are maybe in a in an oil slick after it rains.

Aaron Lindenberg: on the streets right and this kind of these amazing colors are again all about constructive and destructive interference of various colors coming from from the light around us and and the structure here is reflective of the fact that there are many different.

Aaron Lindenberg: large scale variations in the thickness of the very thin walls of the bubble, and as these as the thickness of these this bubble changes it effectively changes which colors destructively or constructively interfere.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so um So those are examples just kind of illustrating the process of.

Aaron Lindenberg: diffraction interference, but the key point for the for this lecture and for this for this work is that we can actually take advantage of this process and really use interference and diffraction as a ruler to measure distances and measure the spacing between objects.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so what i'm showing here. Aaron Lindenberg: is an example where you imagine, this is just a sort of a an animated picture it's not a it's not a not a real photograph but imagine the surface of a lake.

Aaron Lindenberg: And you drop to two rocks into the lake and that probably all of you have noticed the sort of circularly expanding waves that emanate from each point in the lake when you drop that stone.

Aaron Lindenberg: Right, and so what you can see here is that the waves from each of these to. Aaron Lindenberg: Each of these two sources are interfering with each other and creating this kind of you know, amazingly complex pattern of of of high of parts, where the where the water waves are high and parts, where the water waves are low.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so the key point here about using this as a ruler. Aaron Lindenberg: Is that effectively and I won't take you through the math of of all of this, but imagine that you could measure the sort of structure this amazing.

Aaron Lindenberg: In sort of image, the structure of all the regions where things are bright and all the regions places where things are are dim.

Aaron Lindenberg: You could take this information and effectively work backwards and figure out learn something about.

Aaron Lindenberg: The sources that created these waves in the first place, and in fact you could use this type of measurement to really extract the distance between these two sources and and many more things like this, so this is the essence of of how we're doing the diffraction.

Aaron Lindenberg: In in materials to try to measure the separation between atoms the only differences out, we have to zoom in in wavelength, so we can't use light.

Aaron Lindenberg: which has wavelengths on the visible light somewhere right around here and in the spectrum as wavelengths of the order of hundreds of nanometers to a micro right so micron.

Aaron Lindenberg: Well, you know the width of a human hair is something like 10 or 100 microns so already you know one micron or hundreds of nanometers is a really short length scale.

Aaron Lindenberg: But in fact this is still much, much larger than the spacing between atoms so we actually have to move.

Aaron Lindenberg: way way down that this curve toward high frequencies toward the X Ray range, in many cases and it's down here where we're talking about wavelengths on the order of.

Aaron Lindenberg: You can see 10 to the minus 10 meters Okay, this is oftentimes called one engstrom it's a it's one 10th of a billionth of a meter you know really unimaginably short distance, but nevertheless it's these types of lane scales, that we need to.

Aaron Lindenberg: probe if we want to actually really watch materials and understand how they're operating and actually lay like I won't even just be talking about light.

Aaron Lindenberg: In terms of doing these measurements will also be talking about electrons turns out, you can also use electrons to do the same types of diffraction.

Aaron Lindenberg: I won't explain how we do that, right now, but that's That would be a good thing to ask in the question and answer session, if you have thoughts about this okay so.

Aaron Lindenberg: um So how do we actually create these X rays well i'm not going to really off here i'm I just don't have enough time to really tell you all the details about how the sources work.

Aaron Lindenberg: Essentially, this is what you're seeing on the top image here is a picture of the three kilometer long Linac.

Aaron Lindenberg: The linear accelerator that was built at slack in the 1960s and represents now one of the world's brightest X Ray lasers this produces bursts of of light at X Ray wavelengths.

Aaron Lindenberg: which can be used to do the type of diffraction interference that i'm talking about here that's pretty much all say about the about the sources right now.

Aaron Lindenberg: But we can come back to them okay So what if you apply this What if you actually had the sources of X rays, and you now try to measure the structure of something.

Aaron Lindenberg: And one of the most beautiful and and and famous examples of of really you mean and at the atomic scale and measuring the structure of something and then learning something important is this example.

Aaron Lindenberg: Of the structure of DNA, which probably many of you know right is is a double helix and over here on the on the far left.

Aaron Lindenberg: This is an example of the original X Ray diffraction pattern that that Franklin Watson and Crick measured in 1953.

Aaron Lindenberg: And what you're seeing is is essentially an interference pattern in the end, just like the waterway, the example that.

Aaron Lindenberg: That I talked about before, and it was from this measurement from this diffraction pattern that they were able to work backwards and actually conclude that DNA has this double helix like structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then, of course, once you know it has a double helix, then you start to understand, not just the structure, but you start to understand understand something about how the DNA functions and you start to think about replication and.

Aaron Lindenberg: And all kinds of really important aspects in biology Okay, so in the next slide i'm going to try to give you a really simple and.

Aaron Lindenberg: I think beautiful way of of understanding the origin of the of this diffraction pattern that I show here the key aspect, you can see, as the sort of you'll see is this x like

Aaron Lindenberg: Like feature that you see in the Center of the image i'm going to try to explain to you in very simple terms what how this X is related to this helical structure of the DNA.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so so to do this i'm if we were doing this in person, I would I would actually do the experiment, but but but.

Aaron Lindenberg: Over zoom these experiments won't work that well so i'm going to just show you the result of a couple of different experiments that will allow us to build up and and understand the structure of DNA and the origin of this X so.

Aaron Lindenberg: This first on the top here this first example is the know a really simple example of a diffraction pattern, this is what you would measure if you showed you could do this experiment at home, if you have a laser pointer or something like that.

Aaron Lindenberg: If you shine a laser through a dense array of wires Okay, and you make these wires quite closely space to each other, then what you will get is.

Aaron Lindenberg: Essentially, a pattern like I show here this sort of a range of spots with bright and dark spots spread out in both directions and you can kind of already understand the origin of this, if you think about the light waves.

Aaron Lindenberg: passing through this the set of wires as you move, you know from one end of the image to the other, as you move left right what you're effectively changing is the relative phase of.

Aaron Lindenberg: The waves scattered from each one of the individual wires and that's what gives rise in the end to this sort of range of bright and dark spots it's just constructive and destructive interference.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so that's the sort of diffraction pattern and the key point to take away from this is, in particular, is that this diffraction pattern is set up in a line perpendicular to the axis of the wires.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so, in particular, if I imagine doing the same experiment, but I rotated my grid of wires by a by a little bit then as you might imagine the diffraction pattern also effectively.

Aaron Lindenberg: Just rotates Okay, and we could even think now about doing a measurement where we super pose.

Aaron Lindenberg: Two sets of wire grids one where the wires are oriented vertically and one where the wires are oriented horizontally.

Aaron Lindenberg: And I think you might might imagine that, in this case, what you would get is something like shown here right we're now, instead of just a single set of lines you measure actually a 2d grid of.

Aaron Lindenberg: Of spots, the way to think about this is that you know essentially. Aaron Lindenberg: That the set of lines on the left, give rise to a line, and then for each one of those distracted lines those beams can also diffract to the other direction and create a new set of lines this defines essentially the 2d grid that you're seeing here.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then the final step is we say well all right, well, what happens if. Aaron Lindenberg: Instead I rotate one of these these two sets of grids with respect to each other, and now I think you could imagine that, instead of getting a grid, where the angle between the vertical and horizontal lines is 90 degrees.

Aaron Lindenberg: You would create something that which looks much more like this X like structure. Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so what's the connection between this and DNA well, if you look if you zoom in on the structure of DNA here i'm just showing like a zoom in up like a spring or you know, a simple helical object.

Aaron Lindenberg: And what you can see here i've tried to draw the lines associated this way, you can see is that a helix is is.

Aaron Lindenberg: The first order a diffraction grading and the end, and in fact it's two diffraction gradients so you have a set of lines going from from.

Aaron Lindenberg: diagonal in one way and then there's another set of lines going the other way, so, in the end. Aaron Lindenberg: This kind of helical structure really corresponds is exactly like the bottom image it corresponds two diffraction patterns to two diffraction gradients rotating with respect to each other and so that's the simple way of.

Aaron Lindenberg: Understanding the origin of this X like like structure, I learned this from from from this this amazing way of thinking about this from a from a great YouTube video.

Aaron Lindenberg: Michael Mould, and you can you should check that out, if you want to learn more about this okay so.

Aaron Lindenberg: Now you understand how we actually do these structural measurements and how we zoom in and actually can really see the structure of materials and devices at the atomic scale so now, I want to tell you a little bit about the human brain.

Aaron Lindenberg: And, and how the brain works and try to motivate, in particular, the real new experiments that were at that we're about to get to OK, so the brain is is a is an amazing amazing kind of thing.

Aaron Lindenberg: There your brain and you might know is made up of synapses and neurons there's something like 10 to the 15 synapses.

Aaron Lindenberg: In the human brain something like 10 to the 11 neurons these are really unimaginably large numbers.

Aaron Lindenberg: The number of neurons in your brain is is comparable, this is one way to think about it it's comparable roughly to the number of stars in the Milky Way galaxy okay um the the neurons and synapses are connected, you might know by the sort of long wires your brain really is like a.

Aaron Lindenberg: In many ways anelectrical structure, you know with electrical signals bouncing back and forth, through it, and if you took these axons these axons these wires that connect one neuron to another.

Aaron Lindenberg: And you connected them all together and line them up, then amazingly enough within a single human brain, you would get a distance of the order of 10 to the sixth kilometers 1 million meters.

Aaron Lindenberg: So this is roughly the distance from the earth to the moon, and all of this is wrapped up in inside your head.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then, on top of this, we all know that the brain is human brain is powerful and and it's capable of achieving amazing things it's also amazingly energy efficient.

Aaron Lindenberg: And this gets now back to the some of the early things I started the top the talk talking about the problems that current electronic devices.

Aaron Lindenberg: run into current computers, based on transistors run into so the human brain runs on on just about 10 Watts of power, it only weighs a few pounds.

Aaron Lindenberg: runs at a at a frequency of about 10 hertz. Aaron Lindenberg: And if you compare this to a supercomputer a typical supercomputer these numbers are always going up, but a supercomputer uses a disk an average power on the order of 10.

Aaron Lindenberg: megawatts, so this is 1 million times the average power of the human brain works uses if you add if you took all the computers and data centers in the world.

Aaron Lindenberg: It turns out that the total average power added up across the whole globe is is a number of the order of .2 terawatts okay or a terawatt is is ten to the 12 Watts.

Aaron Lindenberg: And this is roughly the the just just the computers and data centers in the world us about 10% of the world, electricity, so this, this is an energy problem it's an it's a problem that that impacts things like climate change and and how we all live.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so it's this type of it's these types of arguments that that motivate. Aaron Lindenberg: For us, the idea of trying to think about asked to ask the question well, can you find material systems that in some way operate the way the brain works.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so I have to tell you a little bit more about in particular how neurons work and how they function in order to now to then next explain the properties of how.

Aaron Lindenberg: How we can find materials that that effectively mimic the the properties and the functionality of a neuron so what i'm showing here is sort of a zoom in picture of a sort of a single neuron connected by an axon over here so.

Aaron Lindenberg: At the input of the neuron what we have is a effectively a series of what are called action potential, these are electrical signals that might be just a few milliseconds or 10 milliseconds and duration.

Aaron Lindenberg: And these are inputs, these are the inputs that come into a particular neuron. Aaron Lindenberg: And the way this neuron works, one of the key kind of properties, the key functional properties that allows your brain.

Aaron Lindenberg: To compute the way it does is based on on on a property called integrate and fire, so this is roughly what the neuron does it effectively is seeing these pulses come in and it's got a well defined sort of threshold.

Aaron Lindenberg: Each time a pulse comes in the voltage the potential within that neuron effectively goes up and the neuron is kind of designed to say all right, once this threshold, once this voltage overall.

Aaron Lindenberg: reaches a certain overall threshold once i've gotten a certain number of pulses coming into the neurons that it says Aha i've gotten 10 pulses or whatever it is, and I will now output and fire a.

Aaron Lindenberg: signal which will then communicate to the next neuron down the line, so these are kind of amazing electrical properties, the communication from from one neuron to the other is mediated.

Aaron Lindenberg: By by the synopsis and this involves in turn Ionic motion crossing kind of nanometers scale gaps within your brain.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so this this the sort of key property here is this is this kind of threshold like behavior this idea that that it can effectively wait and acquire a certain number of counts.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then, once it's reached a certain threshold, it will fire, so I was trying to think of a good way of explaining this and in the process of preparing for this talk, I was perusing some parental self help.

Aaron Lindenberg: Pictures websites and I found this picture, and so, for me, this this is maybe, at least if you have kids This is one good way of of understanding the this kind of the origin of this kind of integrate and fire, this is a parent.

Aaron Lindenberg: Who has been sort of driven to his limit and eventually just snaps right by as kids and so, in many ways it's this type of threshold like behavior that that underlies how neurons actually work within your brain.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so a threshold voltage switch and, in many ways, another way of kind of thinking about this is that this is sort of like a material with a memory right.

Aaron Lindenberg: So, so why do I say that well in some kind of magic way the neuron is able to kind of count the number of pulses that comes back payment it's not just looking it's not just thinking instantaneously about what's coming in.

Aaron Lindenberg: This neuron knows that oh wait, you know nine up there pulses nine other action potential pulses have already arrived now here's the 10th and i'm going to use this and now i've crossed my threshold and i'm going to actually fire.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so um can we find materials and now we're getting close to the to the main story of this talk, can we find materials, which in some way mimic this behavior.

Aaron Lindenberg: And in fact we can and to explain how this works I to first tell you a little bit about the properties of materials, in particular the properties of phase transitions and materials.

Aaron Lindenberg: So this is something that again many of you, I think, are probably aware of and understand on the top here.

Aaron Lindenberg: Is this example of just a glacier you know floating somewhere off the coast of Antarctica right, and so we all know that that water and ice are really in some sense, you know.

Aaron Lindenberg: Both made up of h2o hydrogen oxygen and the only difference is in some sense is how the atoms molecules are effectively arranged so in the case of ice, there are a range and kind of a quasi periodic array and they form a.

Aaron Lindenberg: Solid kind of structure, whereas in the case of liquid water once you melt ice of course liquid water flows and as a completely different kind of structure right, and so the transition from liquid water to ice is an example of what we call a phase transition.

Aaron Lindenberg: So on the bottom I show another kind of cool example if you're old enough to have seen this movie, this is one of the early Superman movies, I think it's maybe the first one.

Aaron Lindenberg: From the early 1980s, and so in this picture what Superman does is he picks up a piece of coal so coal, you know, is made up of carbon.

Aaron Lindenberg: And he effectively takes it in his hand squeezes it with all of his strength and then, when he opens it he's transformed the coal into a diamond so diamond is also made of carbon.

Aaron Lindenberg: But it's corresponds to a different atomic scale structure so he drove it, this is an example of what you might call a solid solid phase transition, where you switch.

Aaron Lindenberg: One material from one structural phase to another so it's this property that we're going to essentially take advantage of when we try to.

Aaron Lindenberg: make this kind of material with a member okay so here i'm going to give you now one kind of simple example, maybe simples the wrong word.

Aaron Lindenberg: But one example of materials which can effectively mimic this in particular this type of integrate and fire functionality.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so, these class of materials are called phase change materials and and they're called this because they have essentially amazing properties to effectively switch between one structural phase and the other so over here.

Aaron Lindenberg: On on one side i'm showing an example of the crystalline phase of a typical phase change material all the atoms were arranged in a perfect Crystalline lattice.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, now it turns out that by applying electric fields or applying voltage pulses are applying light pulses, or even temperature.

Aaron Lindenberg: You can effectively switch the material from this crystalline phase to what's called an amorphous phase, and the only difference here now.

Aaron Lindenberg: Is that the atomic scale structure of this material has been switched it's been changed to now something where the atoms are kind of arranged in a much more chaotic and then and kind of random orientation.

Aaron Lindenberg: So these materials amazingly enough can be switched reversibly millions of times.

Aaron Lindenberg: back and forth between between these different structures and associated with these kind of dramatic changes in the structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: are dramatic changes in the electrical conductivity of these materials so you might know that you know, a typical material.

Aaron Lindenberg: You know, you might have heard of resistors. Aaron Lindenberg: You know that many materials have an effective resistance which measures, a section essentially the flow of current in response to a voltage and, and this is oftentimes characterized and plotted.

Aaron Lindenberg: In terms of what's called an IV curve so on the on this plot here on plotting current on the on the y axis.

Aaron Lindenberg: On the X axis apply in a voltage and so most materials have sort of a linear resistance, if I apply a larger voltage than more electrons flow.

Aaron Lindenberg: And typically if I double the voltage that I apply, then I also double the current okay so that's sort of the typical response, this is not how phase change materials effectively behave.

Aaron Lindenberg: So here i'm showing what you measure, this is what the IV curve looks like this is some real data some raw data for a particular type of phase change material.

Aaron Lindenberg: And you can see it's got a completely different kind of response back so on this plot here imagine kind of kind of starting at zero voltage in the.

Aaron Lindenberg: effectively in the amorphous structure of the material, the structure over here, where the material it's kind of largely non conducting and has very low resistance very high resistance.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then very low current flows, so what you can see, is, as you increase the voltage as you increase the driving force essentially initially nothing happens no current flowing.

Aaron Lindenberg: But then suddenly you reach this kind of threshold like behavior this kind of magic response right around here.

Aaron Lindenberg: At this point, something magic happens a switch happens the material actually eventually switches into the crystalline phase and it follows kind of a really complex path through this through the space.

Aaron Lindenberg: And that eventually when you imagine now kind of reducing the current you can see, you go back now on a different line.

Aaron Lindenberg: So this is an example in many ways of a material with a memory right i've effectively when I tried to apply.

Aaron Lindenberg: When I tried to apply a voltage and measure the current that's flowing this material knows whether i've previously applied a voltage which switched it into the.

Aaron Lindenberg: New phase or not Okay, so you can already maybe start to see the connections between between this type of of.

Aaron Lindenberg: Integrating fire behavior and threshold like behavior and the properties of phase change materials.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so um and, in fact, and I won't take you through all the details of this, but other groups around the world have really managed to to really make real examples of integrating fire functionality.

Aaron Lindenberg: So here is another example of a phase change material embedded between a top and bottom electrode.

Aaron Lindenberg: And what you can see here what we're plotting is the conductance as a function of the number of pulses that you apply number of electrical voltage pulses that we apply to the switch.

Aaron Lindenberg: So, each time we apply a voltage atoms move around and some complex pattern.

Aaron Lindenberg: But, overall, the conductance does initially doesn't change like I was showing on the previous slide. Aaron Lindenberg: But then right around some sort of magic number of pulses of the order of 10 or nine or something like that you can see, this dramatic switching occurs.

Aaron Lindenberg: The conductance shoots up and this corresponds to now a structural change within the material and the material is effectively switching from one structural phase.

Aaron Lindenberg: to another, so you can really see now, this is sort of a direct example of the integrate and fire kind of threshold like behavior that that occurs in these materials.

Aaron Lindenberg: And people have thought of many even more complex ways of kind of doing this. Aaron Lindenberg: here's one more example of kind of an array where you imagine at each this sort of a what's called a crossbar geometry, and each one of these kind of crossing points and each one of these nodes.

Aaron Lindenberg: Is a small nanoscale bit of material and we can individually address each one of these nodes apply and electric field when we do this, we effectively cause atoms to flow from one electrical gap.

Aaron Lindenberg: across a small nanometers scale gap, the other, and we can effectively modulate at each point we had every crossing pointed here the conductivity the resistance of of the structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so, essentially, we can actually effectively do this now. Aaron Lindenberg: and use these types of approaches to to actually do a whole range of kind of important processes information is important for image recognition and and information processing matrix multiplication.

Aaron Lindenberg: Things like that, but the crazy thing is the amazing thing about all of this is that no one's ever been able to really directly probe the switching processes before.

Aaron Lindenberg: And this is what really motivates us to apply the type of techniques that are that we're talking about to go beyond this kind of.

Aaron Lindenberg: You know, working in the dark working blind and really start to see the structures that were the complex structures that we're dealing with and use this to.

Aaron Lindenberg: To understand something deep about how these materials actually work, so, in the end, now I think i've gotten to the main part of the talk now.

Aaron Lindenberg: We can now do exactly the type of imaging that I showed. Aaron Lindenberg: You know these original egerton movies, but now we can use the fraction to really see at the atomic scale what atoms are doing, and we can actually in many cases, we can.

Aaron Lindenberg: oftentimes we have we can apply some kind of trigger Okay, so in this this sort of cartoon schematic here we're applying light pulses these light pulses are kind of initiating a reaction starting some process.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then we can kind of take a snapshot with the short pulse of X rays or a short pulse of electrons measure the diffraction pattern.

Aaron Lindenberg: This creates this kind of know pattern of bright and dark spots on the screen and from these we can work backwards and actually learn something about the structure and now watch the structure as it evolves as a function of time.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so i'm gonna give you kind of for now now to very quick examples of some some experiments along these lines.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then I want to zoom in for the final sort of five minutes of the talk. Aaron Lindenberg: and talk about the, the most recent results were really applying these types of approaches to really watch a device as it functions under pulsed electric fields and so on.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so here's an example of an experiment looking at exactly the type of phase change materials that I that I was talking about just about five minutes ago, these materials that can be reversibly switched.

Aaron Lindenberg: between a crystalline and an amorphous structure so i'm way over here on the on the far left i'm showing the diffraction pattern measured.

Aaron Lindenberg: From one of these structures and it's initially it's in this amorphous disordered structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: And you can see, if you look at this kind of diffraction pattern it's got this very broad and diffuse features, and this is reflective of the fact that the atoms within the structure are really roughly randomly arranged not perfectly randomly.

Aaron Lindenberg: But, but quite randomly arranged, and the result is that you don't get very nice well defined interference pattern, so you don't get lots of well defined bright spots it's much more of a diffuse like structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so now what i'm showing here. Aaron Lindenberg: Just next to this is the same same material, but now the only thing we've done is be fired a single optical pulse of this material and we've effectively switched it.

Aaron Lindenberg: From the amorphous phase into the Crystalline phase, and now you can see that, instead of having this kind of broad diffuse like structures.

Aaron Lindenberg: it's got now much more sharp well defined peaks and this is reflective now the fact that we formed little kind of crystallized this material, where the atoms are arranged in this perfect periodic lattice.

Aaron Lindenberg: So this is sort of before and after images, but we can actually kind of put this together and make a kind of a real movie here and so now on this plot here on plotting the dynamics of how the diffraction pattern is changing.

Aaron Lindenberg: Across about seven orders of magnitude, in time, so we start down here right around time zero right around kind of a couple of pico seconds on the X axis here is basically.

Aaron Lindenberg: it's what i'm really plotting is like the radio coordinate of these diffraction images over here, so you can see, at the bottom here we've got this very broad diffuse light structure reflective of the fact that we have this disordered overall structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then, as a function of time, as you move up on this plot, you can see the diffraction pattern is evolving following the application of a single laser pulse.

Aaron Lindenberg: So initially we form some different type of structure, this is actually an intermediate phase of the material that's never been observed before.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then on even longer timescales, you can see there's now some sort of magic threshold like response, where the material, at a time scale of the order of hundreds of nanoseconds or a microsecond.

Aaron Lindenberg: Effectively, suddenly switches into the Crystal and phase and that's and that's captured by by the emergence of these now very well defined narrow diffraction peaks reflective of the of the crystalline structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so um so that's just one simple example there's a lot more, I could say about that.

Aaron Lindenberg: But, but the first order that the takeaway is that we can apply these types of experiments to really watch these transitions as they happen, we can start to learn something about the pathways materials follow as they.

Aaron Lindenberg: switch between one structural phase and the other and already you can start to see examples here where again just like when you zoom in on the on the.

Aaron Lindenberg: Someone dropping something into a glass of milk you start to see these amazing complex structures start to emerge.

Aaron Lindenberg: here's one other kind of interesting and pretty pretty interesting and pretty cool example taken from the field of what of what are oftentimes called two dimensional materials.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, and so, so this sounds complicated but, but in fact we're all familiar with with these types of materials you've ever used a pencil pencils are made of graphite and and if you zoom in on the structure of graphite graphite it turns out.

Aaron Lindenberg: is effectively what's called a layered structure it's made up of many atomically thin layers of carbon one stacked on top of the other on top, on top of the other.

Aaron Lindenberg: And the layers themselves are very, very weakly bonded with respect to each other. Aaron Lindenberg: And it's this process that you're taking advantage of whenever you write with a pencil as you scratch the pencil across the page what you're doing is kind of sheering off.

Aaron Lindenberg: One layer a few layers of of this of the of the graphite and transferring it from the pencil to the paper.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so, this this interaction force this force that holds one atomic layer to the other.

Aaron Lindenberg: Is is is an important force it's called the van der waals force, in fact, it's the same force that that geckos take advantage of and when they hang upside down from from flat surfaces.

Aaron Lindenberg: And this this idea that you can effectively take advantage of these types of weak interactions has really.

Aaron Lindenberg: represented a really a new direction in the field, you can imagine, now that's what's shown over here on the far left you can imagine stacking material one material on top of another and synthesizing new types of structures.

Aaron Lindenberg: You can imagine controlling the relative twist of these materials are sliding one material with respect to the other.

Aaron Lindenberg: and so on and so we in some in some recent experiments, we tried to take advantage of this. Aaron Lindenberg: And again i'm only going to sort of scratched the surface of this, but we essentially measured the the first of all, the diffraction pattern of an important class of these two dimensional materials.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then, what we did was we fired light pulses at it. Aaron Lindenberg: And we found by measuring essentially watching the twinkling of the stars, the intensities of the of the spots that explained to you encode the atomic scale structure, we were able to see that what we're actually doing was.

Aaron Lindenberg: kind of creating what's what we call it an interlayer sheer it's kind of. Aaron Lindenberg: shown here and schematically in this picture, right here we're one atomic layers maybe slides the left and other slides to the right.

Aaron Lindenberg: The next one, slides to the right, and this whole process is actually oscillating back and forth on amazingly fast timescales on Pico second time scales this process if you live in California, you should know about shear.

Aaron Lindenberg: You know, you might know that that in earthquakes earthquakes are oftentimes divided into longitudinal waves, these are compression waves that that kind of compress objects, as they propagate and then also shear waves.

Aaron Lindenberg: in which the structure is kind of sliding transversely to the side as the way to effectively propagates.

Aaron Lindenberg: So these experiments what we were able to do was effectively modulate the structure dramatically of these different materials, and in fact form of kind of what we call the topalogical switch.

Aaron Lindenberg: I won't tell you too much about about the origin, or what what this word topological means, but this will be again a good good place for questions if you're interested in this.

Aaron Lindenberg: And we've taken this even further we've actually taken the same type of material and we've now integrated into real devices and and applied electrical voltage.

Aaron Lindenberg: voltages to the system and it turns out that that again by applying voltages to these systems, you can kind of control at the atomic scale how one layer slides with respect to the other, and in fact you can take advantage of this.

Aaron Lindenberg: To to. Aaron Lindenberg: find new ways of encoding new types of information in these materials again related to the topological properties of these materials.

Aaron Lindenberg: So the key takeaway from from all of this just to try to connect to what i've already talked about these are examples of really ultra fast types of.

Aaron Lindenberg: motions atomic scale kind of distortions of one layer with respect to the other and just from the fact that you're only sliding these layers very small distances.

Aaron Lindenberg: Effectively, you need very low energies to actually drive this process, and you also can can effectively.

Aaron Lindenberg: drive this process and very fast time scales, so this these aspects of energy and time effectively.

Aaron Lindenberg: You kind of win, win twice when working in in these types of geometries right you win in terms of speed and you win in terms of energy costs by take by finding materials, where you have very weak interactions.

Aaron Lindenberg: Connecting one atomic layer to the next. Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so now i'm in the very last part of the talk i'm going to tell you about the most recent experiments that we did we really now approach this limit of really trying to look at at at a real electronically driven device.

Aaron Lindenberg: And material which really does mimic the way the human brain actually works, the way that the way neurons actually work.

Aaron Lindenberg: Really exhibits this type of threshold like behavior and i'm going to show you how we can use these types of experiments to really learn some new things about about how these devices actually work.

Aaron Lindenberg: So here's a kind of a very rough schematic of the experiments and and how these experiments actually work in this case we're actually not using X rays.

Aaron Lindenberg: To do the diffraction we're actually using pulses of electrons it turns out electrons also have a wave length.

Aaron Lindenberg: And we're using these kind of very, very short wavelength electrons compressed into a narrow bunch to effectively take snapshots of the structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: So here, you can see, this this this little sort of white in this picture this white sort of pulse of electrons is traveling from left to right on your screen and heading toward this electronic device.

Aaron Lindenberg: This device we're applying electrical bias pulses to. Aaron Lindenberg: We have top electrode structures on this thing and what we're going to do is we're going to.

Aaron Lindenberg: Essentially switch this material from one structural phase to another and then again try to watch as this as this process actually happens so here's the electron getting a little bit closer.

Aaron Lindenberg: To the switch and that it passes through and we measure the diffraction pattern on the back screen and then we apply all the principles that we just talked about to do the synchronized electron photography.

Aaron Lindenberg: So the key thing here the key idea here is, we can effectively apply this voltage pulse to switch we can change the structure of the material and the question is, how does this material actually switch from one phase to another.

Aaron Lindenberg: Can we find new ways of encoding information in this can we find new ways of doing this with low energy minimizing the energy costs for switching and so.

Aaron Lindenberg: So the material that we were looking at is is really amazing material, and again I won't really tell you too much about it right now but it's a material called the Vanadium dioxide.

Aaron Lindenberg: And this material really does in this kind of simple form showed on the top here, where you have essentially just sort of a bit small region of the Vanadium dioxide sitting between a top and bottom electrode this really does in many ways mimic the properties of.

Aaron Lindenberg: neurons in your brain, you can actually within circuits like this, create the analog of action potentials but now, where the pulses here, the effect of pulses are much, much shorter than than that, then the action potentials.

Aaron Lindenberg: In your brain, you can, in fact, by applying voltages above a certain threshold, you can make this material really act like it has a memory.

Aaron Lindenberg: And in fact you can switch it from an insulating phase that's what i'm showing showing on the on the very far left over here.

Aaron Lindenberg: This sort of blast the Stanford glass which is, which is transparent and. Aaron Lindenberg: And insulating and doesn't conduct electricity and just by applying a single pulses of electricity, you can switch it into a metallic phase which effectively conducts electricity and the dynamics of this process has been something that's been debated and and.

Aaron Lindenberg: It something that's been people have been interested in for for many, many decades now say there are lots of other kind of cool applications of this material.

Aaron Lindenberg: You can think about making, for example, things like smart windows right so imagine that you know, in an office building, if you could just apply a.

Aaron Lindenberg: Electrical signal and effectively control the transparency of the window, you could really have this could have a big impact.

Aaron Lindenberg: On the overall energy costs that the that the building uses right if on a very hot day if you can dim the window and effectively make the glass less transparent.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then on very cold days you can make the window fully transparent and absorb all the energy from the sun, the miskin have really big effects on on the overall energy budget of of buildings, so all of these properties are kind of encoded in this kind of magic material, VO2.

Aaron Lindenberg: Okay, so so in this in these type of because I already showed you one on the top, this is, this is the example of the phase change materials, one example of the material with memory.

Aaron Lindenberg: On the bottom here i'm showing really our measurements of these these types of devices and you can see each to cut a long story short, you can see, first of all way over here on the on the farside.

Aaron Lindenberg: If I measure the IV curve by apply voltages and measure currents, then in fact the the this material really does have this really complex like behavior it has a threshold switch associated with it.

Aaron Lindenberg: The material can be switched into a new structural face it really acts like a material with a memory, and in fact we can drive these type of switching processes over and over and again millions and millions of times okay.

Aaron Lindenberg: So in the actual experiments, we were interested in trying to measure both the structure of these materials, how the atoms were actually arranged moving.

Aaron Lindenberg: But then also simultaneously find ways of measuring how electrical current and the dynamics.

Aaron Lindenberg: of how electrical current is also moving to the material capturing both the structure, what the atoms are doing and then also simultaneously what the electrical how the electrical properties of this material we're actually changing as well.

Aaron Lindenberg: And so, all of this was kind of integrated into this kind of fairly complex device structure where we had electrodes.

Aaron Lindenberg: We had bunches of electrons coming in, and we were able to apply fast rising voltage pulses, in order to make these measurements of the structure and the electrical properties.

Aaron Lindenberg: And again there's probably much, much too much for me to to really say about this right now, but I want to just sort of just.

Aaron Lindenberg: spend one minute and just walk you through some of the data that we see from this so in these plots here what i'm showing is on in the in this kind of purple curve here, this is a plot of the electrical properties of the material the resistance of the material.

Aaron Lindenberg: So what we're doing is we're applying a voltage pulse right around time zero Okay, and you can see there's a couple of just really surprising and interesting things that happen first of all, we apply this voltage pulse.

Aaron Lindenberg: right around here, but you can see that, after the voltage pulses applied the resistance kind of doesn't change for a while right it just stays constant.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then suddenly it switches after some time delay, so this kind of time delay this period where the material has already been kind of triggered it's been pushed but hasn't actually switched is called the incubation phase.

Aaron Lindenberg: Of the material and so, for the first time, we can actually interrogate and measure the structure of these materials during this incubation phase, for example.

Aaron Lindenberg: And we can start to ask questions like what is the pathway these materials actually follow as they transform.

Aaron Lindenberg: And to cut a long story short, that sort of key takeaway from these experiments, is that we really can, first of all, watch the transition from this insulating phase to this conducting phase, but we also see evidence for a different structure.

Aaron Lindenberg: structure not previously seen before, under this type of of excitation condition is electrically driven condition.

Aaron Lindenberg: And, in particular, this intermediate structure is also conducting but it involves a much, much more subtle structural distortion.

Aaron Lindenberg: So we can imagine now is that just by taking advantage of this kind of threshold switch we found a way to effectively modulate the electrical properties of the material, while driving much smaller displacements, of the atoms.

Aaron Lindenberg: And this, in turn, we think, and we don't know the answer to this yet, but we think should should really give rise to much, much lower energy costs for for effectively the driving this switching.

Aaron Lindenberg: So, in the end, what would the key takeaway here is the observation of this of this kind of intermediate phase and, more broadly, this opens up new possibilities for.

Aaron Lindenberg: for creating new types of materials, you can apply voltages and really take advantage of this types of these types of dynamics to create new kind of properties of new materials with interesting functional properties.

Aaron Lindenberg: All right, so so as I mentioned the very beginning of the talk.

Aaron Lindenberg: I really feel like like where we're at the very really only scratched the surface of this work and and certainly there are many more.

Aaron Lindenberg: Questions remaining than answers i'm for me I kind of feel like like you're on a you're climbing a mountain.

Aaron Lindenberg: And you cry and you kind of turn the corner and suddenly in front of you is this amazing kind of valley of mountains and glaciers and and rocks and and and you see this vast expanse and and for me this is kind of.

Aaron Lindenberg: Where I where I think we are at this point here in the field where we've kind of really done some very first preliminary experiments, but we have this kind of really broad range of possibilities that we can apply these approaches to to to really push this field into new directions.

Aaron Lindenberg: So um I wanted to just end the talk by just very briefly thanking some some very important people.

Aaron Lindenberg: In particular, that the key people that really kind of lead this work and two of them are actually here with us as panelists and i'll introduce them formally in just a second.

Aaron Lindenberg: One is a Aditya Sood, he's the one who led the work on Vanadium dioxide and Jun Xiao here is a.

Aaron Lindenberg: person who led the work on on the two dimensional materials and then additionally Edert Sie who also was closely involved in in this 2d materials work.

Aaron Lindenberg: Many other people on contributed really closely and strongly to this work, we wouldn't have been possible without this type of collaborative effort that that makes.

Aaron Lindenberg: Science really fun so with that, I think I will thank you for your attention and I will turn things back over to Michael temporarily before we start the question and answer session which i'm very much looking forward to.

Aaron Lindenberg: Michael are you there.

michael peskin: Yes, so I look, thank you very much there's a lot of very cool stuff in this in this lecture and now we'll talk about it in a little more depth um, let me just tell the audience will have about 20 minutes of question answer.

michael peskin: And then, at the end of it um there's a survey that our team would like you to answer so if you would please take just a couple minutes after the end of the Q&a to fill that out we'd really appreciate it so Aaron once you go ahead and introduce the panelists.

Aaron Lindenberg: yeah Okay, so we have to um to important panelists here, these are two guys, who have really utmost respect for scientists, Aditya Sood is currently a postdoc in a staff scientist here at Slac.

Aaron Lindenberg: i've worked closely with and and and and he really lead this work on on this electrically driven transition in Vanadium dioxide.

Aaron Lindenberg: And then Jun Xiao, he was formerly he was a postdoc working with me.

Aaron Lindenberg: Until recently he's just started a an assistant Professor ship at the University of Wisconsin and and he's the person who who you know, has really been thinking about the the 2d materials and things like that so they're both here to help and answer any questions that you might have.

michael peskin: Okay well um I encourage everybody to open up the Q&a box and type in your questions, but a number of people have done that already so um.

michael peskin: Oh, there we go that's me a number of people have done that already so let me start with those questions so first of all, it at the end of the talk you describe this very cool.

michael peskin: piece of equipment with two pieces of metal and this Vo2 synpase like thing which is between the two biggest that and I knew it's quite small So how do you actually make that thing.

Aaron Lindenberg: yeah yeah so that so in experiments that we've done so far, these are kind of micron scale.

Aaron Lindenberg: And and but we're definitely interested in pushing too much, much smaller lane scales as well, maybe actually Aditya, you should say something about how you actually made these devices, since you were the one who actually did it.

Aditya Sood: Sure yeah that's a really good question and something that we took a long time to figure it out.

Aditya Sood: So the key challenge with these experiments, is that you want to make this magic material which is Vanadium dioxide or whatever you're using to compute.

Aditya Sood: Really really thin because you want to be able to send electrons through it, so the thickness of these devices is about hundred nanometers or 10s of nanometers that's really.

Aditya Sood: it's a challenge, and so you have to make these devices in a way that they're actually suspended in vacuum.

Aditya Sood: And then you also have to find a way to actually engineer and put down metallic electrodes on top of them and put all of this inside this vacuum Chamber which is shooting electrons through this this magic material.

Aditya Sood: So car does is we use kind of standard lithography techniques very similar to what is used by companies like Intel and so on, to make sort of semiconductor transistors.

Aditya Sood: And yeah so it's a bunch of optical aligning and things like that. Aditya Sood: I think the key thing is, is making these devices and then also integrating the timing of firing these devices electrically with the electron pulses.

Aditya Sood: Which are sort of shooting like bullets through these devices, so that setting and other sort of key aspect to this experiment is the synchronization.

Aaron Lindenberg: yeah I might I might also add. Aaron Lindenberg: One of the other kind of important directions we're working on is is trying to push the time resolution of these measurements, so you can imagine.

Aaron Lindenberg: really trying to make the the transition time the the time in which this electrical pulse effectively turns on shorter and shorter and really start to learn something about the sort of ultimate speed limits for that that underlie how these devices operate.

michael peskin: Interesting actually someone else asked about what is the ultimate speed limit for a device Well, first of all for the device, and then, secondly, for your ability to measure.

Aaron Lindenberg: yeah yeah, this is a great question um well so in the experiments that we've really done so far.

Aaron Lindenberg: We, as I, as I showed in the in those plots we were really looking in those final set of experiments on kind of switching timescales just on the order of microseconds so it's still pretty fast, but it's not that fast.

Aaron Lindenberg: But it turns out that that we, through these experiments and, in particular by comparing.

Aaron Lindenberg: The response that we see under electrical biases with the response under optical pulses we learn something actually very important that let's that's actually.

Aaron Lindenberg: Maybe at least start to speculate about what those ultimate speed limits are, and it may be that there are really possibilities of pushing this too much, much shorter time scales on the order of pico seconds.

Aaron Lindenberg: Rather than the time scales that we've actually measured but we haven't demonstrated that so far. michael peskin: So, with luck, a trillionth of a second.

michael peskin: So, possibly um. michael peskin: So these systems, often have memory and you, you talked about that, but this is something different from computer memory, this is a different kind of memory just amplify that a little.

Aaron Lindenberg: yeah um yeah, this is a good question yeah there's lots of different ways of storing information and in materials, you know.

Aaron Lindenberg: You know within within your computer there there you know people, you can store information in the magnetic properties of materials, for example.