Rapid Beam-switching Allows SLAC X-ray Laser to Multitask

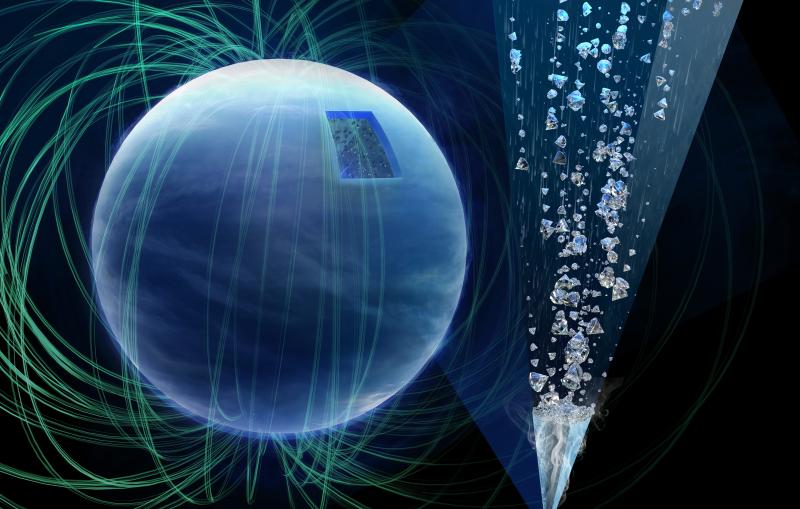

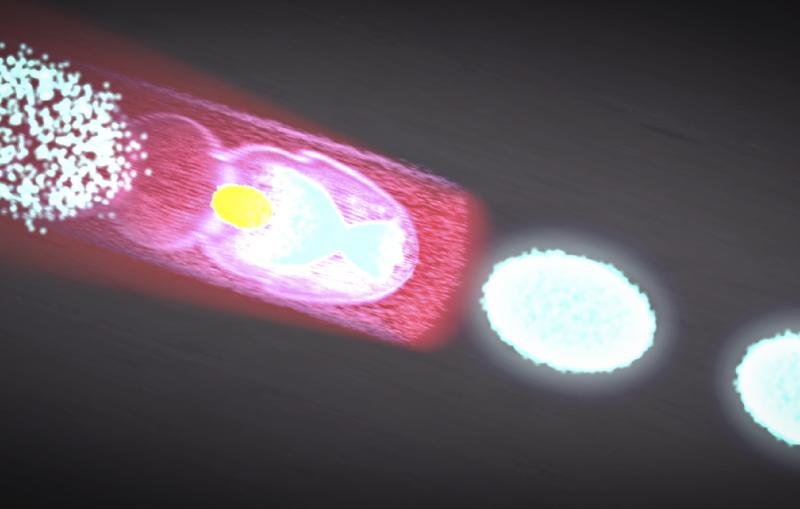

A high-energy SLAC laser that creates shock waves and superhot plasmas needs to cool for about 10 minutes between shots. In the meantime, the rapid-fire pulses produced by SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source X-ray laser, which probes the extreme states of matter produced by this initial laser shot, are unused.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

A high-energy SLAC laser that creates shock waves and superhot plasmas needs to cool for about 10 minutes between shots. In the meantime, the rapid-fire pulses produced by SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source X-ray laser, which probes the extreme states of matter produced by this initial laser shot, are unused.

Now scientists have found a way to make good use of that downtime by diverting the much-sought-after X-ray laser beam to another LCLS instrument, where it can deliver more than 100 laser pulses per second – tens of thousands of pulses during each cooling-off period – to carry out an additional experiment.

The system passed its first test during experiments by LCLS users in May, switching X-ray pulses between a geophysics experiment at the Matters in Extreme Conditions (MEC) instrument and a separate experiment to study the structures of protein and virus samples at the Coherent X-ray Imaging (CXI) instrument.

During that first test, Sébastien Boutet, who leads the scientific team at the LCLS CXI Department, reported, "Everything at CXI is working as when we have a dedicated beam, except for the reduced fraction of time the beam comes to CXI. We're not impacting the MEC experiment at all."

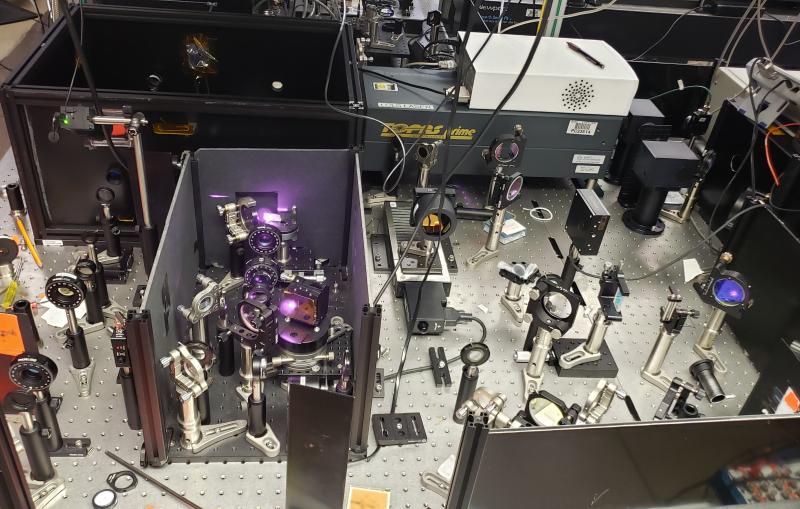

The laser, known as the "long-pulse" or nanosecond laser, delivers high-energy pulses measured in billionths of a second, compared to several other laser systems at SLAC's LCLS that deliver lower-energy, shorter pulses measured in femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second. Its pulses are well-suited to extreme temperatures and pressures required in many experiments at MEC.

Rapidly switching between experiments, one of several methods for increasing the number of experiments at LCLS, is particularly important given the high demand for the X-ray laser. Fewer than one in four scientific proposals to use LCLS can be accepted, and typically LCLS can accommodate only one experiment at a time, though there are plans to run simultaneous experiments on a limited basis through another beam-sharing technique.

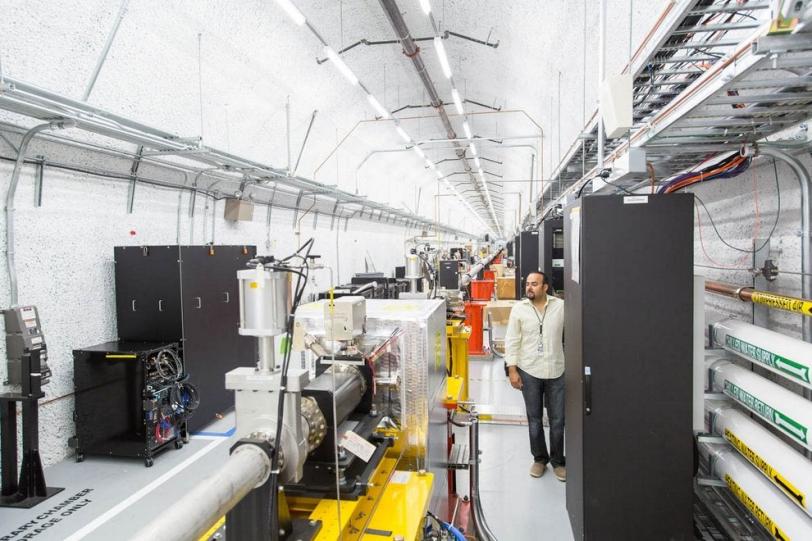

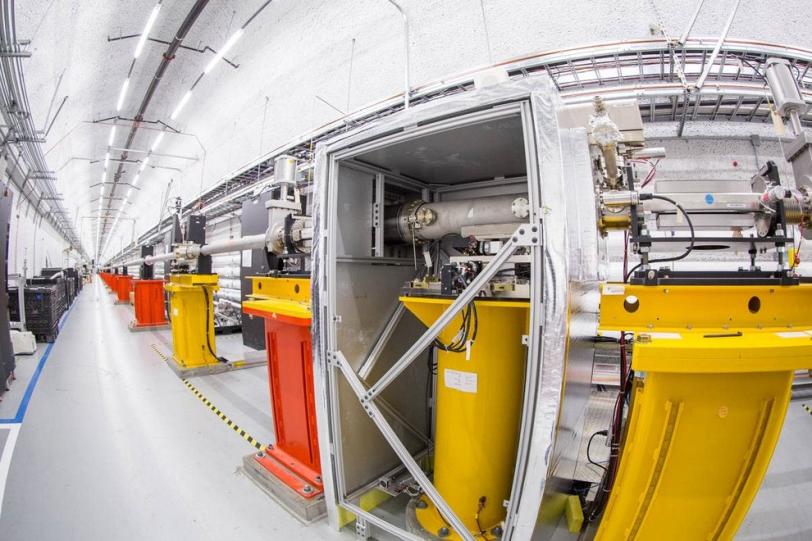

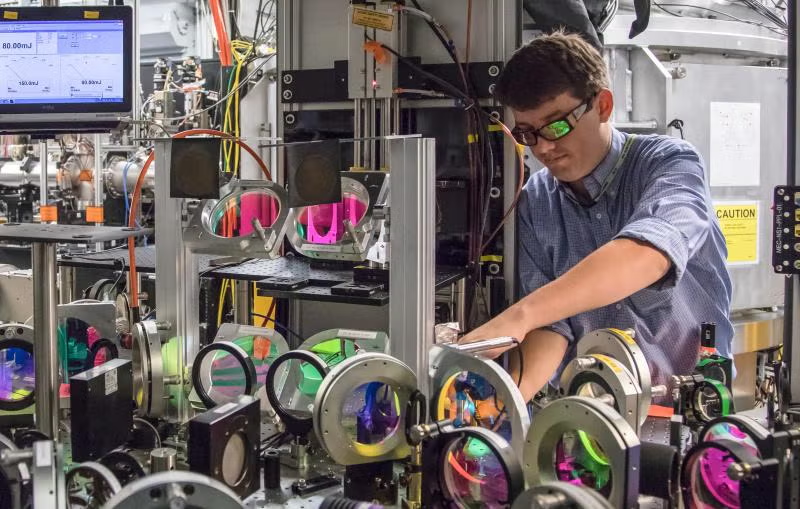

The new method uses a motorized mirror, 240 meters upstream of the MEC instrument's target chamber, that can be moved in and out of the path of the X-ray laser beam to divert it to another experiment. The mirror must maintain a precise, fixed angle, accurate to 1 hundred-thousandth of a degree – about the same precision as aiming for the width of a human hair one football field away -- to carry out the switching.

Philip Heimann, who leads the team of scientists at the LCLS MEC Department, said most experiments at MEC use the long-pulse laser, so the beam-switching effort had been a high-priority project. Work began on the switching system in December 2012, six months after the first experiments at MEC, and the earliest commissioning of the beam switching was in January 2013.

"We had to make sure that the switching could happen reproducibly and quickly," Heimann said.

Moving the mirror into the beam and retracting it now takes 12 seconds, according to Jing Yin, an LCLS controls engineer who led work on the switching technique. Further developments could speed up the switching process, which also requires a rapid opening and closing of the shutter that blocks the X-ray pulses from traveling to the CXI instrument.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory engineers designed the mirror system as part of the original LCLS project.The precision of the mirror manipulator is critical to the switching technique, Heimann said.

He said that during the current LCLS operating run, which began in July 2013, beam-switching will be used during some of the experiments in the CXI Protein Crystal Screening Program, which allows scientists to quickly test whether crystallized samples of biological proteins produce quality diffraction patterns at LCLS that can then be used to determine their molecular structure.